What is an Art Environment?

Art environments are personal spaces like homes, gardens, and studios that have been fully transformed into continually evolving, site-specific, and life-encompassing works of art.

What does the term ‘Art Environment’ mean?

This term is customarily used to refer to immobile constructions or decorative assemblages, monumental in scale or number of components. Art environments may be interior or exterior, and typically include elements of sculpture, architecture, bas-relief assemblage, and/or landscape architecture. Such composite works, produced additively and organically without formal architectural designs or engineering plans, owe less allegiance to folk, popular, or mainstream art traditions and the desire to produce anything functional or marketable, and more to personal and cultural experiences, availability of materials, and a desire for personal creative expression.

They are generally intended to be viewed in their entirety rather than as a grouping of discrete works.

Studies of individual sites usually reveal the labors of a single, passionate worker (an artist in our eyes, but not always in those of the creator), typically—but not always—begun in the later years of their lives.

Although constructions known as art environments typically slip between the foci of most academic disciplines, a worldwide genre of such monumental structures has been defined in the last few decades, thanks in large part to the work of SPACES.

Search the entire SPACES collection

Suggest an Art Environment to include in the SPACES Archives

Art environments exist in every state of the union and every country in the world. They can be large or small and they can exist inside or outside. Most are made to be public, but some are extremely private. Sites can be found in the unlikeliest of places — in a suburban backyard, a remote desert, or in a thriving city. Art environments are often discovered by ordinary people as a result of a wrong turn, or by chance while on vacation. Sometimes they are discovered by following nothing more than a hunch or a “word-of-mouth” lead. The more you learn about art environments, the more awareness you will have in identifying a site you may have knowledge of in your community. Or, perhaps you would like to visit a site that may be nearby on your next road trip.

Art environments exist in every state of the union and every country in the world. They can be large or small and they can exist inside or outside. Most are made to be public, but some are extremely private. Sites can be found in the unlikeliest of places — in a suburban backyard, a remote desert, or in a thriving city. Art environments are often discovered by ordinary people as a result of a wrong turn, or by chance while on vacation. Sometimes they are discovered by following nothing more than a hunch or a “word-of-mouth” lead. The more you learn about art environments, the more awareness you will have in identifying a site you may have knowledge of in your community. Or, perhaps you would like to visit a site that may be nearby on your next road trip.

We invite you to take the time to explore this website, learn what environments may be in your area, and come back often as we continue to add more art environments to our collection

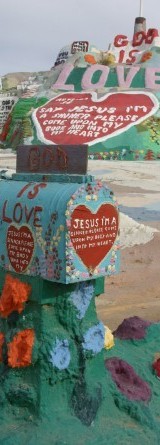

This website is designed to inform and educate anyone who has the desire or curiosity to understand more about art environments. We have learned that art environments usually owe less allegiance to folk, popular, or mainstream art traditions and more to personal and cultural experiences. There are myriad reasons why art environments are built. We have identified reasons such as the expression of love, for politics or freedom of speech (see Sorehead Hill), to tell historical tales (see Wisconsin Concrete Park), or, in the case of Sabato Rodia, a desire to create “something big” (see Watts Towers). Sometimes, just the availability of materials is the impetus for a site (see Bottle Ranch) and in other cases sites are born from deep religious feelings (see Salvation Mountain). In almost all cases, the driving force is an overwhelming desire for personal creative expression (see La Maison de Picassiette).

Documenting and preserving the cultural heritage of art environments are essential components of the study of this genre — yet they may offer significant challenges. In some instances, title to the property upon which the environment was constructed has been contested or is claimed by a governmental entity for flood control, freeway construction, urban redevelopment, or the like; in others the very monumentality and imposing presence of the works has brought issues of public safety and community property values to the fore. Equally significant has been the use of non-traditional materials and unconventional building methods by many of these artists, most of whom worked in an additive trial-and-error mode without thought to long-term preservation needs.

Art environments often challenge aesthetic and conceptual community values at the same time that they are beset by environmental degradations; this combination can be a fatal prognosis for their ongoing stability and preservation. Numerous sites have suffered partial or total destruction — even some that had achieved official local or state landmark status — despite months and even years of legal wrangling by preservation advocates. The creation of personal worlds by non-academic builders — who passionately recycle our society’s discards in an effort to publicly proclaim love of country or religion, retell local histories or tales, or just “make something big,” as Sabato Rodia, creator of the Watts Towers, is said to have claimed — does not bring with it a guarantee of eternal existence. Nevertheless, the tremendous influence that many of these works have had upon the art world, from numerous contemporary artists and art historians to folklorists, would seem to warrant their protection.

Because art environments cannot be hermetically stored, they need continued vigilance and a concerted effort from local community members — backed up by art and preservation professionals internationally — to ensure their survival. Without such advocacy, we risk the ultimate extinction of this extraordinary, albeit idiosyncratic, visual form of roadside Americana.

Donation of Materials

You can also support SPACES through the donation of materials that would be appropriate for inclusion in the archives. These might include artists’ letters or scrapbooks, photographs, audio-visual materials, maps, postcards, books, magazine articles, and ephemera. Please contact SPACES at info@spacesarchives.org to discuss any materials that you might have that you would like to share.