L’Ametlla de Mar (Tarragona)Blas García Camacho (b. September 7, 1935)

Extant

L'Ametlla de Mar, Catalonia, 43860, Spain

It is possible to view many of García’s sculptures and garden elements from the exterior of the fence if the artist is not at home; if he is, he is generally pleased to show off and share his fine work with visitors.

About the Artist/Site

Born and raised in the town of Cazalilla (Jaén) in Andalucía, García began to specialize in carving in that city’s Escuela Profesional de Andújar. He learned a variety of skills there, including working in gold and silver, wood carving styles, surface treatments, and conservation techniques. But carving hardwoods took so long that it was impossible for him to make a living in this manner. He moved to the town of Roquetas (Tarragona) in Catalunya around 1958 so he could find better work, and in 1961 married Josefa Rodríguez Ortiz; they had four children (and now several grandchildren as well). He found a job painting cars and trucks six hours a day in order to earn social security and continued, on the side, to take commissions for furniture restoration. He also continued to carve bas-relief sculptures and furnishings for himself on his own time. In August 1970 he was certified as a Grand Master of the Sculptors and Painters Guild, and he soon became one of five who worked directly with Josep M. Subirats on the lateral façade of Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia temple in Barcelona, becoming the sculptor responsible for the bas-relief work. He produced nine of the twelve Stations of the Cross on that façade. With four children he had to take multiple jobs, however, so he also taught carving as well as restoration of polychrome wood sculpture and furniture at the school and workshop Escola a taller d’art Nou Barris in Barcelona, and was enthusiastic about trying to inspire a new generation of artisans.

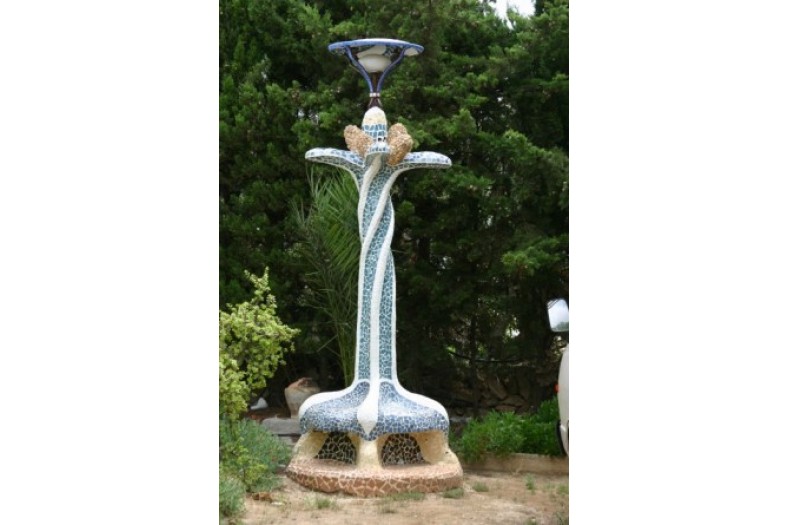

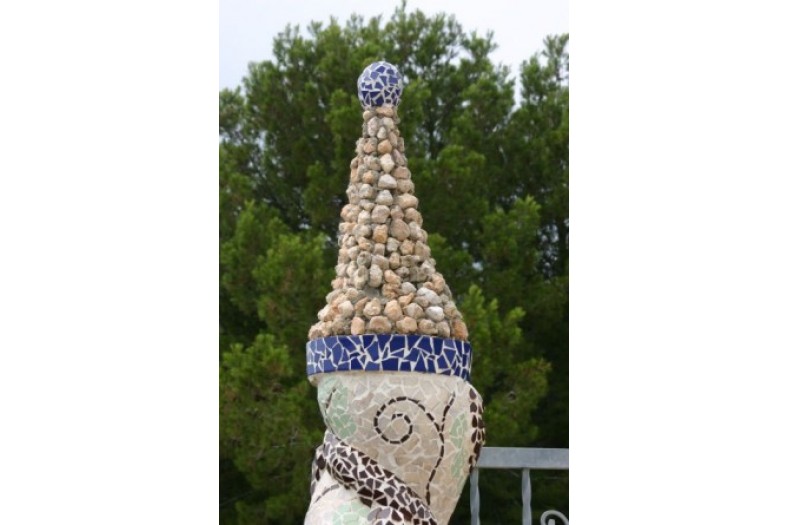

Around 1995, he and his wife retired to a small property on the outskirts of the seaside town of L’Ametlla de Mar, some ninety miles south of Barcelona. The interior of their home is a veritable museum of García’s rich carvings: doors, mirror frames, pedestals, and light fixtures, as well as freestanding sculptures and intricate bas-reliefs of fantasy, contemporary, and genre scenes. In addition, having been inspired by the ceramic trencadís work of Gaudí in Barcelona, Camacho decided to try his hand at this new medium. He had started holding on to broken plates and ceramics that he came across while he was restoring furniture, and he also began to purchase remnant tiles in the nearby town of Amposta.

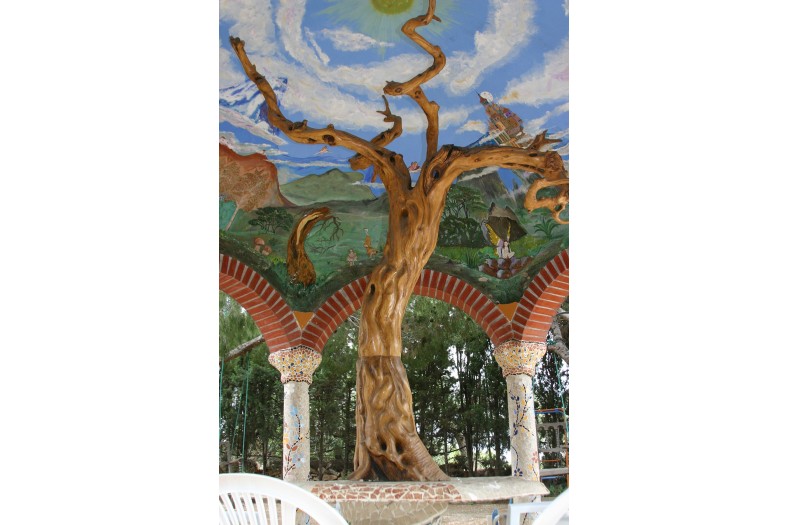

His early work with tile was concentrated in and around the two-story house, including, notably, the image of a winged dragon blowing fire—conveniently aimed directly towards the family’s outdoor barbecue/cooking area. Enthusiastic about the possibilities inherent in this new medium, García continued to work on his new tile work and construction projects for eight or nine hours a day, every day. He built an ambitious undulating overhang for a shed that they converted into guest quarters for when their children visit, as well as an octagonal gazebo: all sides of its exterior are covered with trencadís, and the interior is painted with images derived from a book of fairy tales enjoyed by his grandchildren.

The most remarkable components of García’s garden are several dinosaurs, created to fulfill the wishes of one of his grandsons. García began to construct his first, a triceratops, at full-size scale, roughly 26 feet from head to toe. Without making drawings in advance, but working off of the images in a book, he created an infrastructure of horizontal and vertically crisscrossing steel rods, bending them into the desired form and linking them together at the junctures with small twisted wires. Interior reinforcing rods, beams, and cross members fortify the forms that are then built up with flat plaques of fiberglass that he bends to fit on both sides of the steel rod infrastructure. He roughly packs the cavity thus created with a mixture of cement, gravel, and sand, and adds small pieces of styrofoam to the cement mixture in order to lighten the weight and to reduce the amount of cement that is needed. He has also, at times, used metal screening to help form the sides of the animals. While the construction of the piece is in process, he uses whatever he has available—tree trunks, car tires, etc.—to support such floating sections as the tail or the head as they dry in place. After additional coats of cement he tints the final surface coat green so that the background showing between the tiles appears akin to reptile skin: the craftsmanship here (as elsewhere) is meticulous, and the “skin” of the dinosaurs is sleek and glossy. Using such simple tools as shovels, plastic buckets, ladder, wheelbarrow, hammer, and trowels, García estimates that it took him some five weeks to fabricate the triceratops, and then another week to sheath it in trencadís; he calculates that the completed sculpture weighs approximately seven tons in concrete alone. He thinks that the two other dinosaurs extant at the time of my field research also weigh in at between seven and eight tons each.

García worked until in the spring of 2011, when, without warning, the municipal government slapped him with a 3,000 euro (roughly $4,500) fine for building the sculptures without permits, the equivalent of three months of his subsistence income. They pressured him to take everything down, and García enlisted the help of an architect friend to help him fight this threat, but this struggle took the pleasure out of his work, and deflated his enthusiasm. When I learned of it, I wrote letters to the mayor’s office suggesting that he and his government acknowledge this work as a positive boon to the city rather than as a non-conforming parcel that needed to be brought into compliance or even razed. On Christmas Day, 2011, I learned that the municipal offices had not only pardoned and cancelled the fines, but also were moving toward a “timid recognition” of the value of his work.

It is possible to view many of García’s sculptures and garden elements from the exterior of the fence if the artist is not at home; if he is, he is generally pleased to show off and share his fine work with visitors.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2014

Contributors

Map & Site Information

L'Ametlla de Mar, Catalonia, 43860

es

Latitude/Longitude: 40.8955008 / 0.7722974

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.