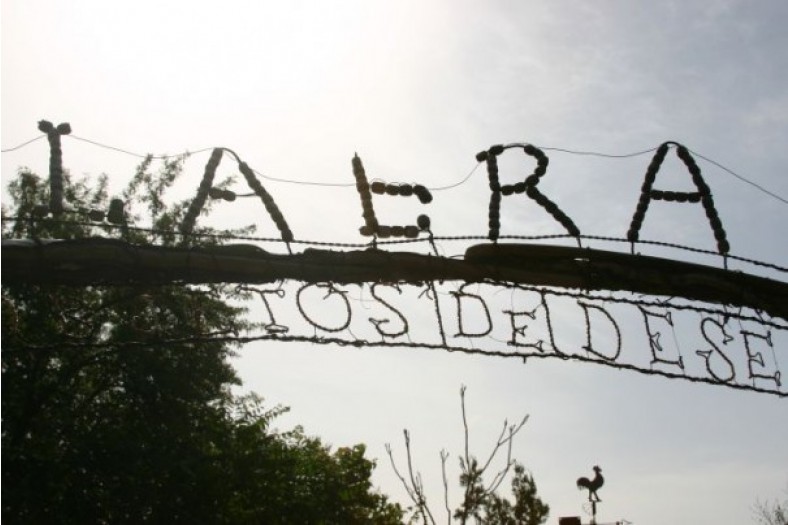

La Era del Tio Cesáreo (Uncle Cesáreo’s Garden)Cesáreo Gimeno Martín (1910–2005)

About the Artist/Site

Cesáreo Gimeno Martín was born and raised in Bueña, a village whose one through road veers off of the main highway and just barely skirts the town, winding its way through the arid hills. The few families generally dedicated themselves to subsistence agriculture. A quick learner, as a young man Cesáreo became skilled at the trade of blacksmithing and, in 1934, married Paz Rubio, with whom he had three children. After service in the Spanish Civil War, he continued not only with steel production from his forge, primarily agricultural implements for his neighbors, but, thanks to his dexterity and a quick mind that understood how machines worked and how things were put together, he also helped his neighbors with their electrical problems, regulated their scales and balances, built them trillos [harrows] with which to thresh their grain, fabricated locks for their homes and out-buildings, and delivered their mail from the back of his scooter. He was also asked by several area churches to fix their clocks and, later, he took charge of the meteorological station in the village as well. He was widely regarded as the smartest man in town, and some of the implements he created have been accepted into the permanent collection of the ethnographic section of the Museo Provincial de Teruel.

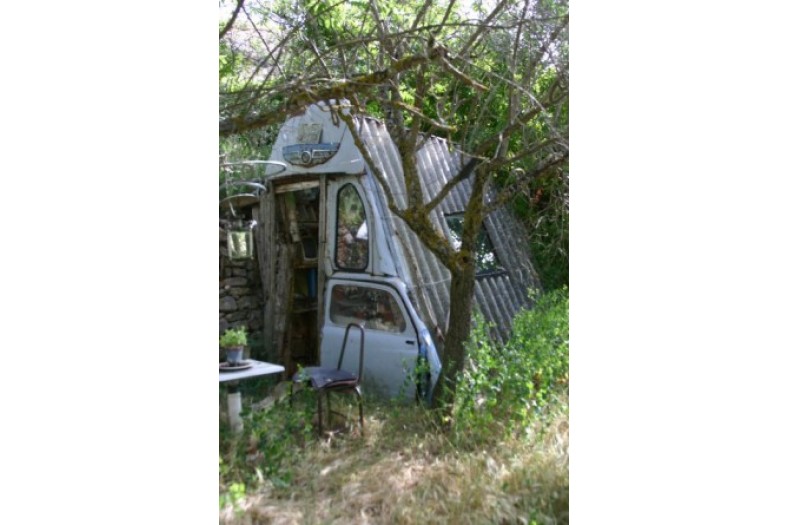

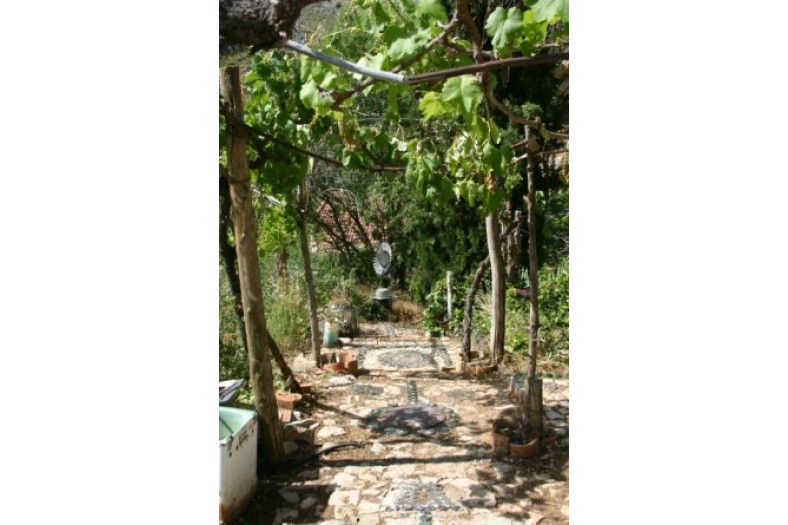

After his “retirement” Tío Cesáreo continued to creatively think about finding solutions to the daily issues that would arise in the village. One seemingly innocuous domestic problem turned out to have a long-term solution that went far beyond the original concern: because his home was right on the road, his chickens would sometimes venture too far away from their corral and would get run over in the traffic. He therefore decided to take them up the hill to a small property that he owned at the end of town, building an enclosure to keep them safe, but where they could still roam and feed. That hilly terrain was rocky, generally unsuitable for growing produce, but once he had his poultry there, he planted some trees, and, as it was slightly remote, he decided that while he was there he would decorate the area, using materials that he found at the dump or that people threw away. His materials of choice were green wine or beer bottles, which he inlaid into the ground in floral and abstract forms.

More interesting than the bottle work, however, are the constructions made from various recycled objects, as well as those twisted out of the wire that was used to bind hay bales. As a blacksmith Gimeno understood steel, but the work he did for the locals was—while at times ornamented with designs—functional and forthright. With the wire, he was able to branch out into representation and even figuration, braiding and twisting the wire, using nothing more than wire pincers to shape them into outlines of such images as an elaborate map of Spain, demarcated by provinces and accompanied by a well-dressed male figure pointing out the little village of Bueña; a map of the zodiac; a flowerpot with flowers; a monk with a hygrometer; a peasant woman with a water jug; various animals; a provocative nude ; and more. Some of these were installed against the walls of the buildings at the garden site, while others were mounted on top of other structures so that their profiles could be seen against the sky. Unfortunately, very few of these works remain on the site. Gimeno wrote out short phrases with his twisted wires as well, formed in a fluid cursive script that recalls the handwriting of earlier days. Among these is the almost wistful “Que verde era mi era” by which he probably meant “how green was my garden,” but which also could be translated as “how green was my time.”

The bulk of Gimeno’s work was carried out between 1980 and 2000—as memorialized in another steel sign—but he continued to go up to the garden until 2004, at which point he could no longer walk up there himself nor see well enough to do so. Although he is warmly remembered—as well as vaunted on the village’s website as a fine example of “the culture of recycling,” there is little or no interest in taking the steps necessary to preserve the site, either by family members or others. Although one of the daughters still keeps chickens up in the coop, none of the children, nor the grandchildren, are willing to invest their time and labor to maintain the place, so the sculptures are rusting and falling apart, and the weeds are growing over the constructions and bottle walkways. Within a very few years, no doubt, there will be few physical reminders on site of Tío Cesáreo’s “garden.”

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2014

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Bueña, Aragon, 44394

es

Latitude/Longitude: 40.7082984 / -1.2668395

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.