A.V. Stagg Art Studio and Wildlife PreserveCharles “Charlie” Stagg (1939 - 2012)

Extant

Vidor, Texas, 77662, United States

The site is on private property and not open to the public.

About the Artist/Site

Charlie Stagg was born and raised outside of Beaumont, Texas; while this area has subsequently been built up, at the time it was very rural, and, with few playmates, young Charlie entertained himself and invented things to do. After completing his local schooling – which all the way through elementary and high school was completely devoid of any art education – he worked briefly doing ship-fitting at Bethlehem Steel, a job so unpleasant that he escaped by enlisting in the Army. He did his military service in Germany, serving as an engineer in the 23rd Battalion and singing as a baritone in the choir, and then returned home, taking a job in one of the coast’s oil refineries, making a good living from this dangerous and dirty work.

Following a short-lived first marriage and divorce, his second wife suggested he take advantage of the G.I. Bill to go to college; although his ambition was restricted by his upbringing and surroundings, he knew he would have to attend McLennan Community College in Waco before he could apply to nearby Baylor University, where his wife had set her sights. Serendipitously, at McLennan he met Texas artist Bob Wade, who became a huge influence; Wade convinced Stagg not to pursue his intended study of commercial art – after all, he was already making a good living working in the refineries, and commercial art wouldn’t provide him with an outlet for his creativity, which is what he felt he was lacking. So, after successfully completing his classes at the community college, Stagg entered Baylor and earned his B.F.A. While there he met sculptor Italo Scanga, visiting locally for an exhibition, who really “opened his eyes” and urged him to pursue his art studies and to join him at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, where he was then teaching. Stagg divorced his second wife, moved to Philadelphia, and earned his M.F.A. at Tyler in 1974; although he concentrated in painting, he found himself increasingly turning to sculpture, thanks in large part to Scanga’s encouragement. Following graduation, Stagg moved around the East, landing in New York for a time, and then back to Philadelphia, but he found living in the city “too easy,” and preferred to live more “on the edge.” Therefore, when his father sickened around 1980, he moved back to his family’s former rice- turned hog-farm in Vidor, a small suburb a few miles east of Beaumont and not far from the Louisiana border.

With the approval – but not the understanding – of his father, and driven by an intense interest in learning about – and pushing the limits of – various materials, in 1981 he began the construction of what would become an elaborate compound with several buildings and structures. Working in a clearing in the densely wooded 31-acre site, he assembled them from an eclectic blending of found objects such as bottles, cans, and concrete, along with logs, branches, and other natural objects. Learning by trial-and-error – the consequence of which included walls that occasionally collapsed – he was never discouraged: it was the process that was important to him.

One of his first projects was the hexadome “Glass Bottle House,” a 24-foot-high domed structure that had been influenced by conversations he’d had as a student with visiting lecturer Buckminster Fuller; this dome was topped with a fiberglass roof and flanked by nonfunctional but intriguing undulating spires. Another building was constructed by arranging a large row of sticks vertically in a circle; he then girdled the sticks with a thick cord that he tightened as he moved up the sticks on a ladder, consequently decreasing the diameter of the building’s circumference prior to its concrete sheathing. The foyer of yet another structure was called “The Church of the Swirl,” as the concrete entrance was dominated with a narrow, swirling chimney. These buildings were not of insignificant size; one of the larger ones had a footprint of roughly 2000 square feet.

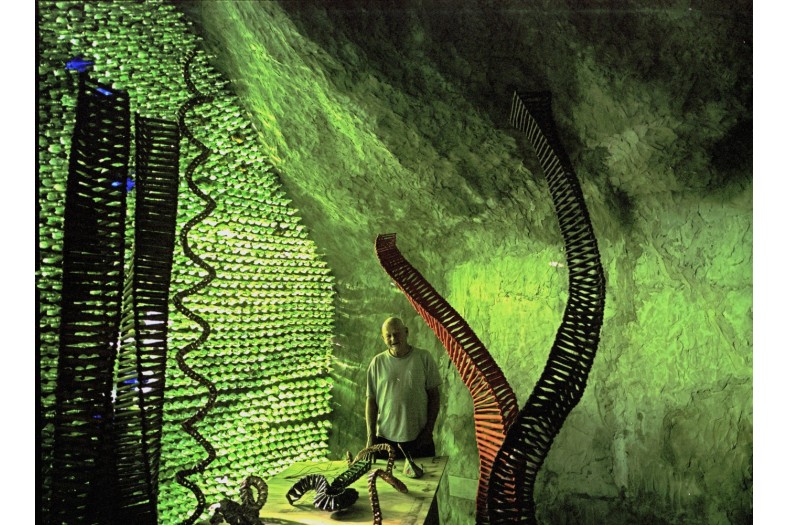

With selections of the exterior walls of the various buildings remaining the grey color of his concrete mortar, the interiors often surprised visitors with the brilliant colors of its surfaces of bottles and cans. In some areas, such as his “Green Room,” the bottles – many beer bottles, many of which he emptied himself – were placed horizontally within and between chain link fencing, butt ends to the exterior, so that natural light could be transmitted through the colored glass to the interior. In addition, the bottles retained heat from the sunlight hitting the exterior façades, making the interior living spaces comfortable even in winter. As Stagg lived alone and without electricity or running water, natural light and heat had to be essential parts of his designs. In some sections, wide-mouthed bottles inserted into the walls doubled as storage cubbyholes for tools, paint brushes, and other small items. He conceptualized the structures – his home – as sculpture that could be lived in.

Stagg continued to work, not only on his environments, but, beginning in the mid-eighties, on a series of discrete works created from wood and found objects that recall DNA helices; he worked on these in the same way that he worked on his buildings – intuitively and improvisationally, without preconceived plans: he just started stacking pieces together, and some ultimately rose to 30 feet in height. A number of these pieces later were incorporated as elements of the infrastructural framework for some of his architectural constructions, but others were sold separately; in the mid-eighties, he priced them at $2 per stick. In 1995, a three-story work, Tree of Life, was exhibited and then ultimately purchased for the permanent collection of Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum.

In 2005 Hurricane Rita ripped through the area, severely damaging the largest dome that had been part of Stagg’s house. A group of volunteers from the Houston area came over with metal, replacing the roof. Then, the following year, the entire structure was further damaged by fire, and most of his wooden helices – along with his collection of work by other artists – were destroyed. The cause of the fire was never determined, although arson was suspected. But he kept working, putting energy into the creation of a concrete hexagonal structure with cut-off ends – to look like a “barnacle” – with a bottle wall and aluminum can roof, in which he passed his first winter after the fire. He had plans to enhance that and continue to build in the same improvisational manner, and he did continue with a variety of constructions. However, in 2012 he fell into an open fire pit on his property and sustained such severe burns that he died within days.

The property was inherited by Michele Woods, Stagg’s only child, the daughter from his first wife. Although they hadn’t been close as she grew up, Woods and her children are now working to preserve Stagg’s compound. The site has suffered some vandalism as well as gradual deterioration from the elements; given Stagg’s incomplete technical knowledge, some of the constructions began their lives in a rather fragile state, and the passage of time in such a humid environment has left its mark. A crowdsourced fundraising drive mounted in June 2017 by his granddaughter Sarah did not really get off the ground, and it is unclear what the future of Charlie Stagg’s environment will be.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2018

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Vidor, Texas, 77662

us

Latitude/Longitude: 30.1316001 / -94.0154541

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.