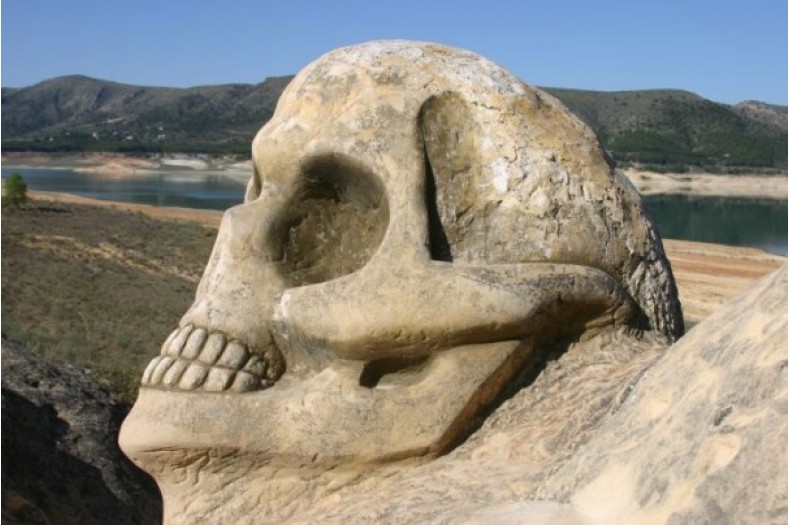

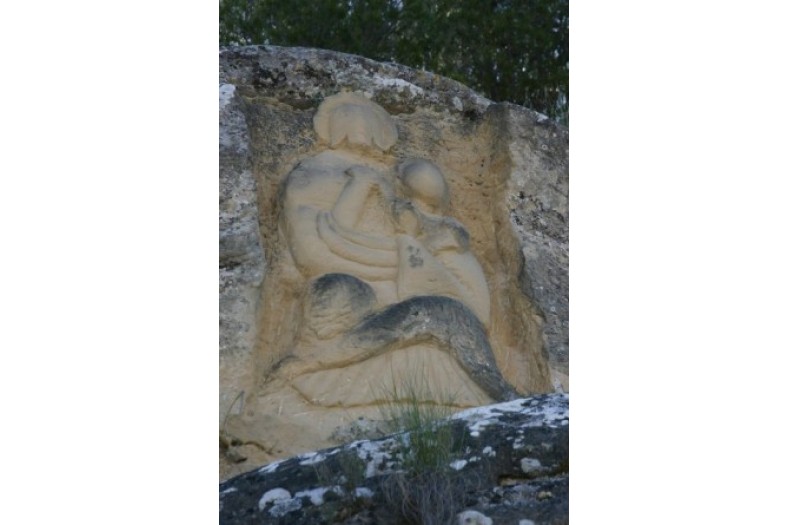

Ruta de las Caras (The Path of the Faces)Eulogio Reguillo Extremera (b. 1949) and Jorge Juan Maldonado Díaz (b. 1943)

Extant

Buendía, Castile-La Mancha, 16512, Spain

The length of the Ruta is approximately two miles, and it is easily located about 2.5 miles north of the village. Cars can be safely parked at the entrance to the forested path.

About the Artist/Site

The harsh and relatively unpopulated high mesa landscape around the reservoirs that form the inland “Sea of Castile” is easily accessed from Madrid, only about 1.5 hours away by national highway. Among those who escaped the city on weekends were childhood friends Reguillo and Maldonado. Neither man had advanced professional training as either an artist or artisan, yet both appreciated and practiced a variety of arts and had family members who were involved in some way. They enjoyed the scenery of the areas adjacent to the reservoir, and discovered that the rocky hills were primarily composed of a sandy limestone that could be easily carved with simple tools. They also had a broader interest in religious sites worldwide and, in 1991, “attracted by a rare magnetism” and a special energy that they felt emanated from this area, began to carve a bas-relief face on a vertical rock wall near the shores of the reservoir, in the area in which they perceived this extrasensory energy was the strongest.

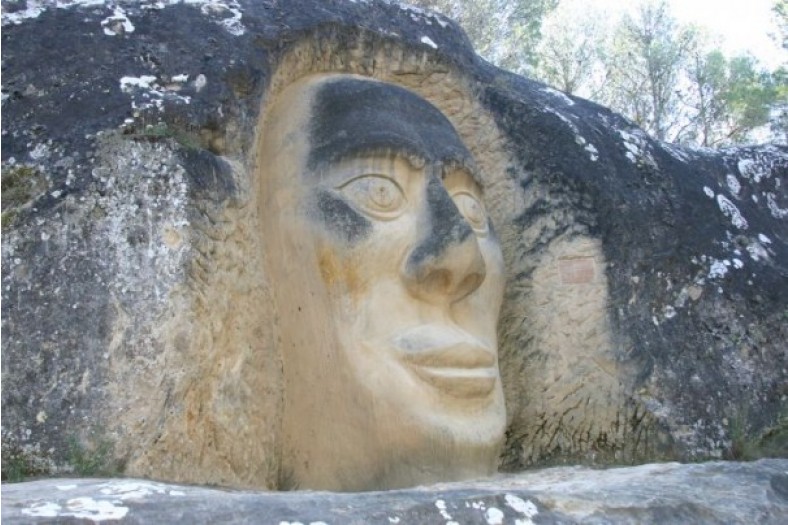

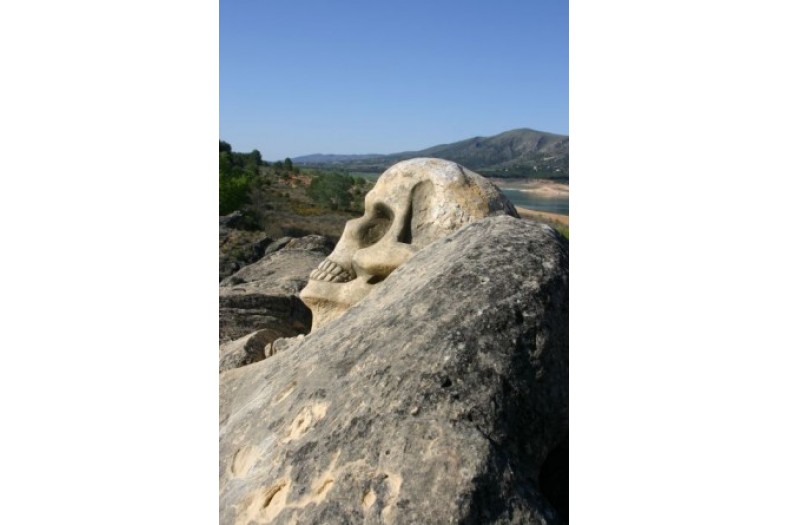

As with most other artists who work in this genre, this project was initiated rather impulsively by these two friends, with no concept of the numbers of works that would ultimately be included nor with elaborately developed plans or blueprints. Inspired by a Costa Rican shaman who visited with the artists at the park and who led them in a ritual offering to the forces they perceived there, Reguillo and Maldonado would often meditate and drink special teas prior to beginning work. Thus fortified, they worked from a combination of representations that they felt would enhance a spiritual experience for others as well, including images drawn from the familiar Catholic iconography as well as other cultural and religious symbols. In so doing, they created a succession of discrete works that, taken as a whole, comprise a series of sequential discoveries as one walks through the pines to the reservoir, each turn of the path revealing new carvings.

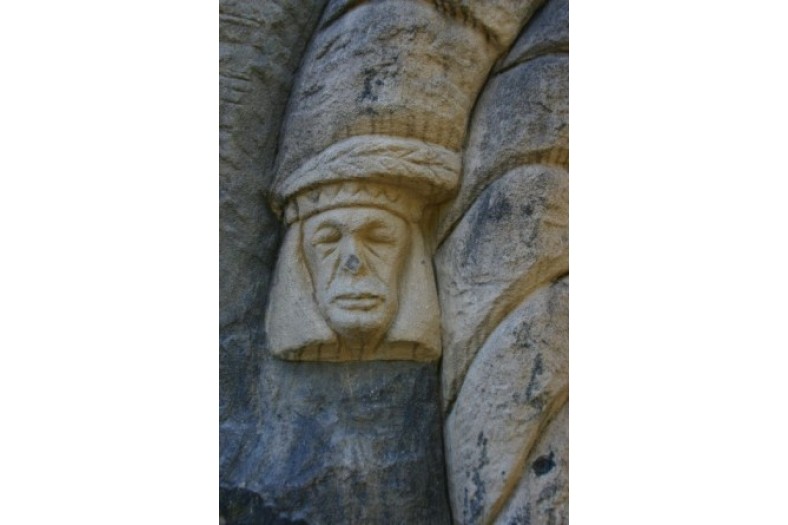

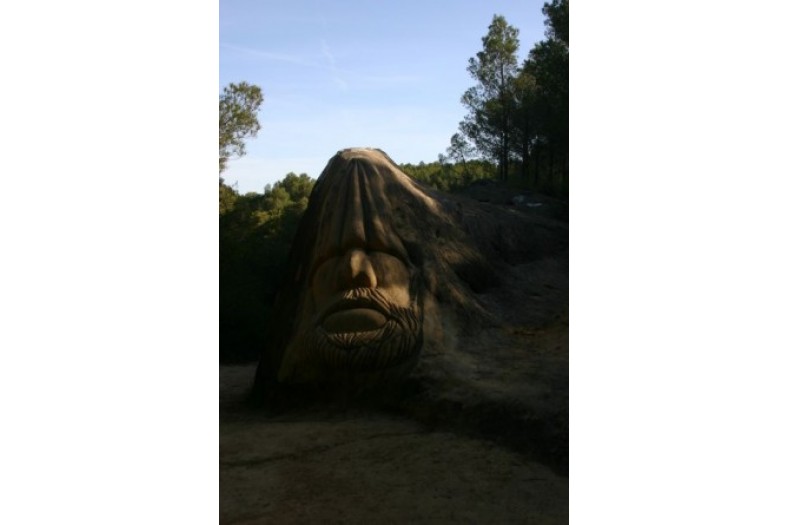

Each work is conceived individually and without regard to any overall conceptual plan or direction, although most do reflect the artists’ general interest in spirituality, and most of the faces display what Reguillo describes as an “archaic smile,” an artistic device the artists use to provide a characteristic quality to the works. Although some of the larger pieces required years of refinement (the Shaman, for example, took four years to complete, and Maitreya entailed roughly six years of work), the sandy quality of the limestone generally allows for the use of simple hand tools such as hammers and chisels, small picks, files, and scrapers with steel nails. The overall volumes are modeled first, with the details added later, paying attention to the forms created by the play of sunlight and shadow upon the surfaces. At times the sheer size of the work requires ladders with security harnesses, but more often the artists scramble up the rock faces and reach over to carve and smooth.

Maldonado’s and Reguillo’s works are compelling primarily due to their monumentality: some are as large as 20 feet high, and most of the others are at least 3 to 5 feet in height. Although the artists indicate that the images they carve are suggested by the rock formations themselves, in actuality it appears that their forms seem to generally ignore the shape of the rocks, and impose on the stone rather than working with or relating to it. Many of the carvings are placed in areas that the artists have flattened out, rather than taking advantage of the bulk and contoured mass of the natural forms; relief overlays are awkward and the proportions are occasionally graceless. The result appears, therefore, to reveal a practical decision about finding a sufficiently large area in which to position the images rather than an aesthetic or sculptural one, in which the medium truly does “participate” in site selection as well as formalist development.

Community response to the bas-relief sculptures has been overwhelmingly positive. To develop and encourage tourist visits, the village has placed numerous directional signs leading to the site along a local road that they have upgraded to handle the increased traffic, the Caras are featured prominently in the village’s website, and the tourist office—aided by grants provided by the national government to promote local attractions—has published several small brochures on the Ruta. In 2007, the two artists received the key to the village of Buendía, and support by the local village and federal agencies appears to ensure that the carvings will remain extant At this point, however, Reguillo is the only artist who is continuing to regularly work at the Ruta de las Caras site. Maldonado, after finishing the monumental face of Chemary in 2001, lost interest in creating any more significant carvings on The Peninsula. The two artists have not seen each other since the ceremony honoring them in the village in 2007.

The length of the Ruta is approximately two miles, and it is easily located about 2.5 miles north of the village. Cars can be safely parked at the entrance to the forested path.

~Jo Farb Hernández

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Buendía, Castile-La Mancha, 16512

es

Latitude/Longitude: 40.3666644 / -2.7568259

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.