Little Program Frank Oebser (1900-1990)

Relocated (incl. Museums)

Menomonie, WI, 54751, United States

c. 1960s -1980

Five sculptures and tableaux are in the permanent collection of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI

About the Artist/Site

Frank Oebser was born January 27, 1900—a debut that placed him in cadence with the century’s beginning and the rhythms of its inventions. His first seventy years were consumed with the operation of a large dairy farm near Menomonie, in central-western Wisconsin. Oebser’s father had come to Wisconsin from Germany as a five-year-old and died in a farm accident when Oebser himself was five. His mother had been born on a farm across the road from Oebser’s house. He recalled, “As time went on we had a good herd of cows. We bought the farm that she [Oebser’s mother] was born and raised on, and hooked it on to ours, and then we got going a little better and got a bigger herd and got out of debt... and here I sit with a house of my own.”

When Oebser was about ten years old he made his first kinetic sculpture. Using a spinning wheel discarded by his grandmother, he devised a water wheel in a stream near the barnyard, but the horses shied from its motion, and he had to take it down. His brothers and sisters married and moved off the family farm. Oebser stayed behind, however, and lived with his mother until she died at age ninety-four. At about that time Oebser retired.

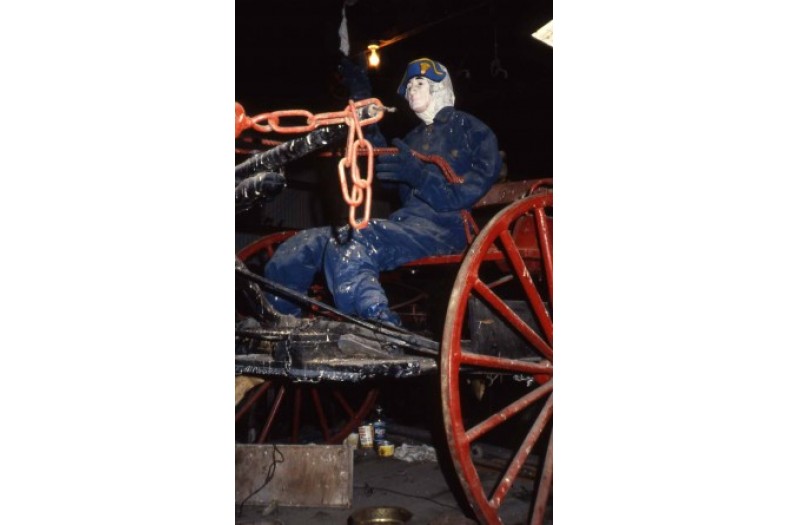

The seventy-some years of intimate involvement with the mechanical inventions of farming left a profound impression on Oebser’s imagination. He had made a few sculptures in the late 1960s, and, after retiring, he spent the open time before him combining and transforming the sounds and motions of antique farm implements with figural and animal forms, creating a series of kinetic sculptural installations. His works were arranged throughout several “museum” spaces—a large machine shed, a few farm outbuildings, his garage, and his yard. Oebser humbly referred to this extended environment as his “Little Program,” a term commonly used to describe church events and other rural entertainments.

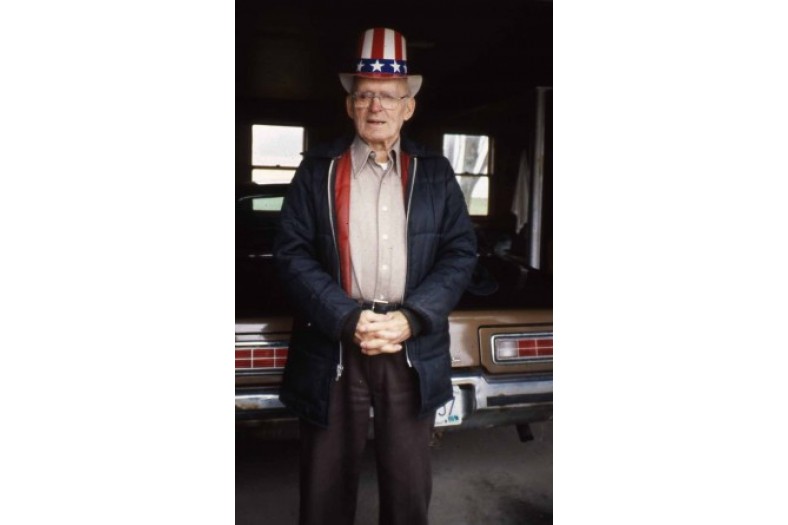

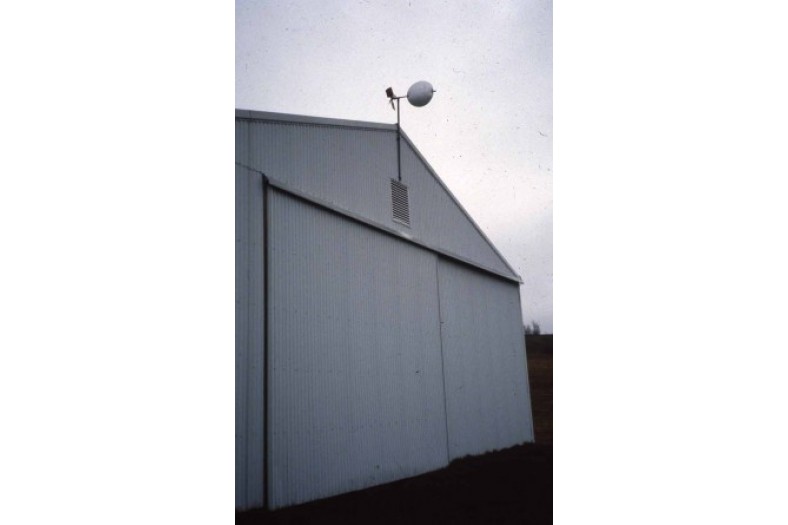

Program was an apt description. Arriving at his pristine farm, visitors found well-kept buildings and a manicured lawn. The only indications of anything unusual were the homemade wooden Ferris Wheel and a merry-go-round in the yard. Then, suddenly, the silence would be broken with a piercing buzzer, followed by pealing bells that were installed on surrounding roof tops, electrified and mechanized. The artist would emerge to spellbound visitors and the program would begin. Oebser began the tour in his garage, showing animated sculptures: a Christmas tree spun raucously on its base, a mechanical chair rocked. By pulling the base of a figure wrapped in white gauze, Oebser demonstrated a walking ghost. If it were a good day, he might appear roaring across the yard on a “grass-mobile”—a snowmobile adapted to snowless terrain—or on a cart driven by a carpet sweeper motor.

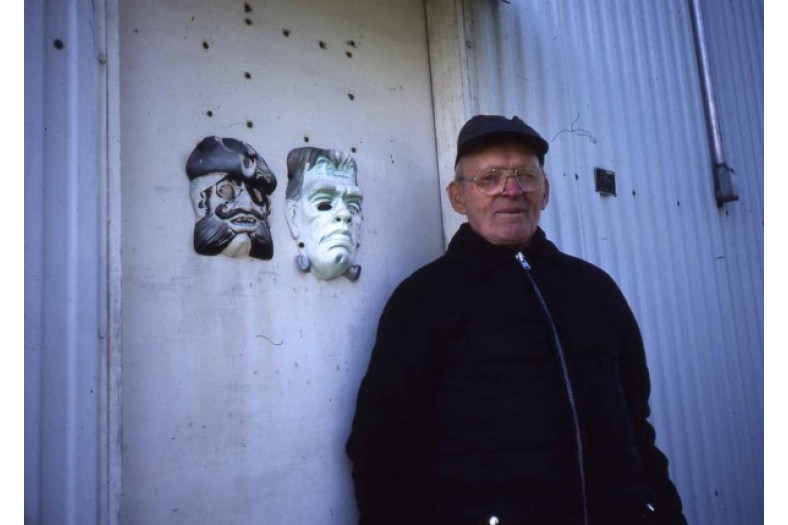

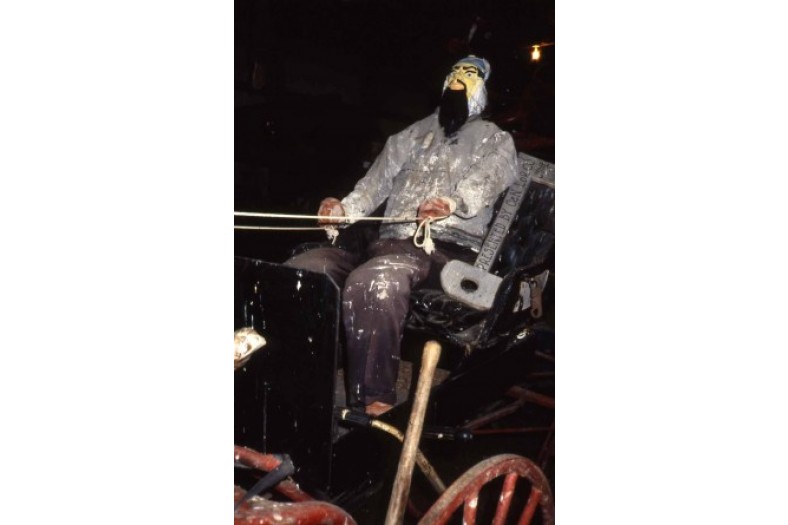

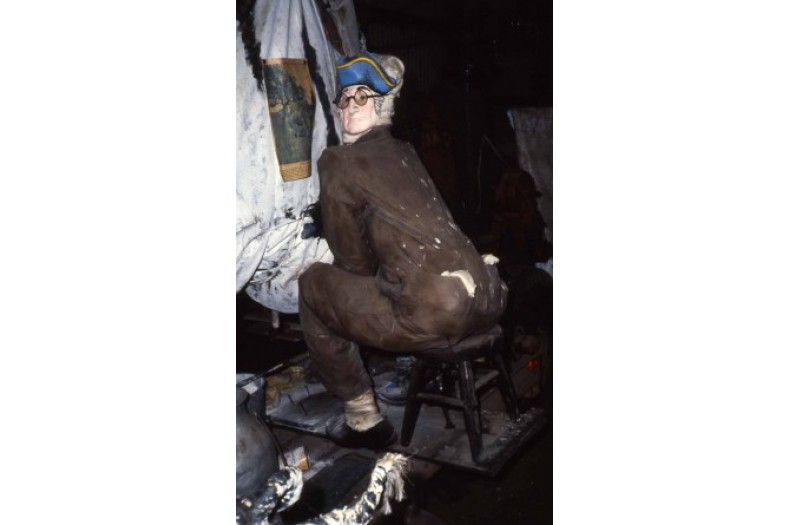

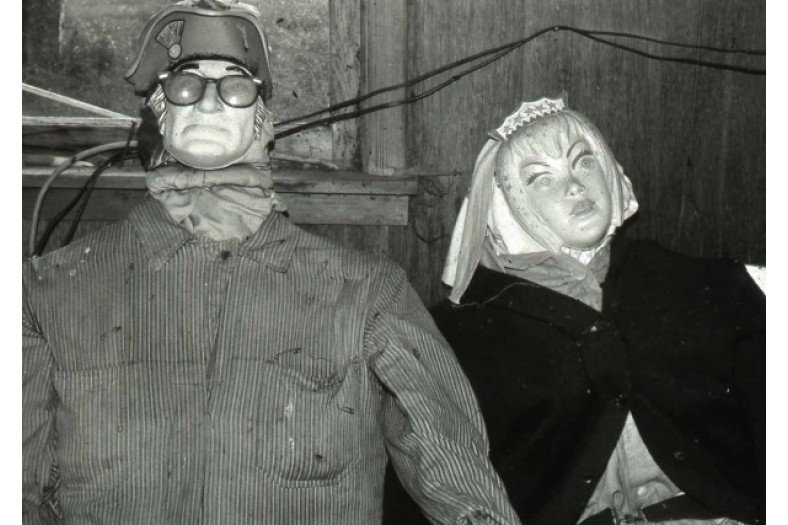

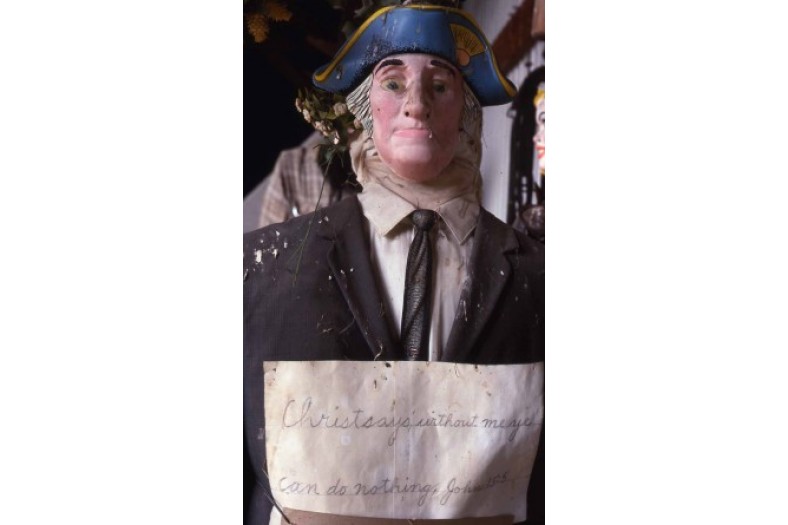

After an illness in about 1988, when he was “kind of down and out,” Oebser made figural sculptures he called George and Martha Washington and placed them in the garage. George, like all of Oebser’s male figures, was an utterly convincing self-portrait. Martha, dressed like a field nurse, may have represented the home nurse who cared for Oebser while he recovered from his illness. Holding hands, the pair conveyed a sense of intimacy, perhaps representing a close relationship for which Oebser, who remained single, had yearned. At a glance, Oebser’s figures resemble the scarecrows and harvest figures—common forms of rural sculpture—made to protect gardens and celebrate the harvest. Made from his own clothing, stuffing, and dimestore masks, Oebser’s figural sculptures possess a peculiar sense of authenticity and personality.

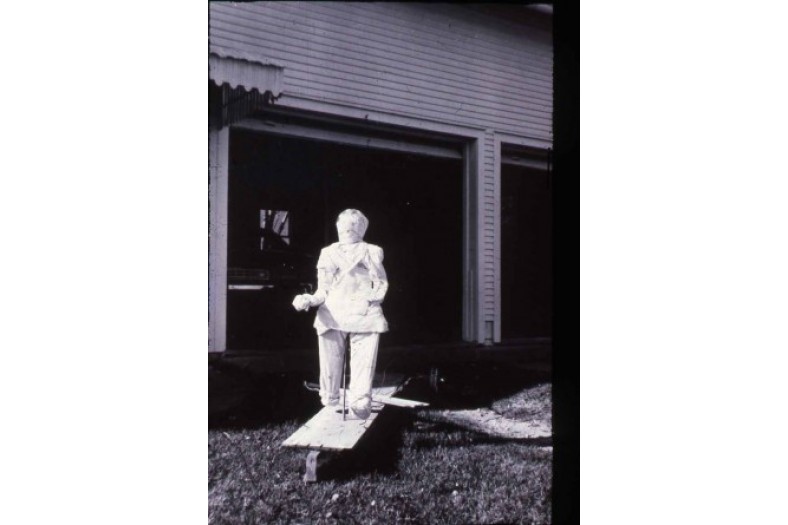

The tour continued in a farm outbuilding, where another figure dressed in the artist’s clothes was animated to walk in place, narrating random radio sounds. Here, visitors became part of the performance, riding on an abstracted mechanical bull and a merry-go-round with hay-bale seats. Another George Washington figure, also in Oebser’s clothing, would be pulled into the yard to wave at passing motorists.

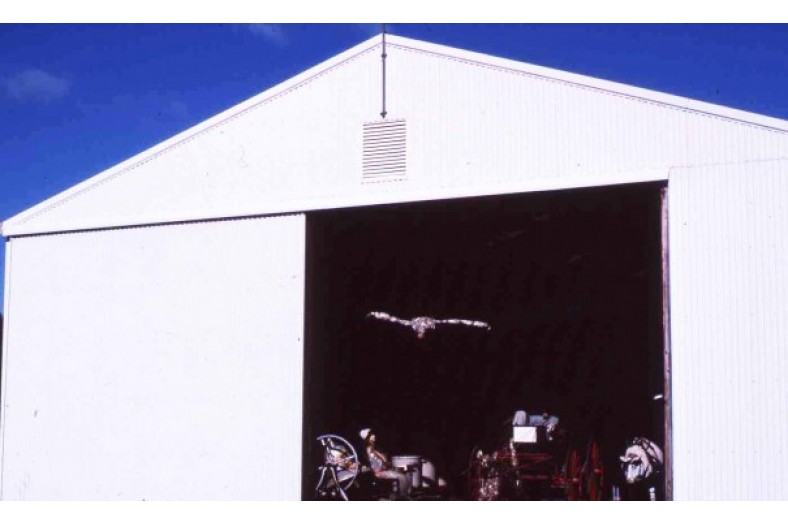

The Program, to this point, was delightful and deceptively simple. Oebser led visitors from one thing to the next, conducting rides, animating his wonders, and interpreting the surrounding collection of antiques and objects that were displayed throughout. He would then ask visitors if they wanted to see his “museum,” which he had created in a typical pole barn on a hilltop. The assumption that it was a generic machine shed was shattered upon entering, and, at this point, the tempo of Oebser’s Program picked up considerably. The entire interior was filled with animal and figural sculptures, an extensive inventory of antique horse-drawn farm equipment, family heirlooms, homemade contraptions, altered machines, and noisemakers. Oebser made the rounds, plugging in extension cords and throwing switches, until nearly everything in the building was moving, shaking, flying, or spinning. As each machine or sculpture was activated, the cacophonous din magnified.

Oebser possessed an uncanny talent for creating figures and animals quickly, with anything at hand. Though crude in appearance, he made piercingly lifelike sculptures that were persuasive, authentic. He patterned them after “life” size. Measuring real figures and animals was the essential step in the building process. Commenting on the distinction between sculpture of traditional media and technique and his own inventions, Oebser said, “I didn’t monkey with a block of wood, like this, and carve ‘em out of wood...them horses are 6 feet tall, they’re life size....If I can’t make ‘em life size, I don’t want ‘em.”

Oebser kept his collection of guest registers in his home, separate from the museum proper. He often said, “I gotta have proof for everything I do...,” and his guest registers were proof of over eight thousand visitors who had been regaled, enchanted, and spun by his Program. He was especially proud of a forty-five-RPM vinyl record produced by local singer-songwriter Linda Russell, who composed a song about him called “Tinker Frank.” Tears ran down his face each time he heard the record, which, for him, was also proof of a kind. Oebser occasionally alluded to a profound loneliness, and the innocence with which he spoke of his “playhouse” revealed another aspect of his Program: he made his friends and animated them. In addition to attracting countless visitors, they kept him company as well.

Oebser was a deeply spiritual man whose faith was a large measure of his Program. He attached signs and scraps of paper with verses from scripture to figures, objects, and wall collages throughout his museum spaces. On the chest of a mechanized, flailing, bell-ringing George Washington figure, for example, was the hand printed message, Christ says without me ye can do nothing. John 15:5. Hanging from the harness on his team of “life-size” horses was a verse of special significance to a man who was continually amazed by the artist within: By the grace of God I am what I am. I Cor.15:10. And he kept one kinetic tableau in his living room. Mounted on a record turntable were plastic crèche figures: Mary, Joseph, and Jesus in a manger. His rationale, as always, was simple: “Well, Ma and I got those as a Christmas present from my niece. Why put it in a box, when everyone can see it?” Plugging in the turntable, the icons of two thousand years would come to life at thirty-three revolutions per minute. Observing the spinning trinity, he once said, “That’s nice. That’s our whole salvation there....”

Reviving his childhood impulse to make a moving, spinning thing, Oebser made an entire, self-contained universe that whirled and spun. Commenting on his series of kinetic installations, he said, “I guess the whole thing’s been...a merry-go-round.” Oebser’s Program effectively confused the distinction between art and life; in his world there was very little space between the two. He worked for over ten years on his Little Program, encapsulating aspects of his life and time period into a kaleidoscopic vision of motion, images, and sound.

Frank Oebser died in his ninetieth year, in 1990. His farmstead was sold, necessitating the relocation of his artworks, which were purchased by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. A number of sculptures were placed with the Dunn County Historical Society and five sculptures became part of the Kohler Arts Center’s permanent collection. A video about his work can be seen here: And So It Goes: Frank Oebser, Farmer/Artist, by Karla Berry and Lisa Stone (1989, 19:44).

~Lisa Stone and Jim Zanzi

Contributors

Materials

Farm equipment, clothing, found objects

Map & Site Information

Menomonie, WI, 54751

us

Latitude/Longitude: 44.875518 / -91.919342

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.