O PasatempoJuan María García Naveira (1849 - 1933)

About the Artist/Site

Juan grew up in Betanzos, a small urban community on the Atlantic coast where the bulk of the population made its living through subsistence agriculture or activities related to the port. Young Juan at first helped his parents in the fields; however, his father died young, and his mother was forced to take on two jobs in order to make ends meet. Given the difficult financial circumstances, in 1869 Juan followed the lead of hundreds of thousands of Galicians, primarily young men, who emigrated abroad to Argentina, looking to make his fortune. He did so, through various businesses including textiles, but also due to his prescient purchase of land in the south of the country, which became extremely valuable with the building of the railroad. Juan permanently returned to Spain in 1893, ultimately resettling back in Betanzos. He began purchasing numerous small plots of land in a marshy and marginal area situated on the outskirts of town; his intent was to create an expansive park which he called O Pasatempo [The Pastime]. He oversaw the removal of at least 30,000 square meters of clay and rock from the higher elevations of his properties, using them to build up the swampy terrain in the lower sections.

The Park would, at the height of its prominence, ultimately cover an area of 90,000 square meters (approximately 22.25 acres). From the very beginning it was intended to provide a visual encyclopedic experience for its visitors, but it simultaneously was designed to promote Juan García Naveira’s faith in a moral approach towards capitalism and progress, teaching by example of his own indefatigable efforts and good fortune, which he attributed to having followed that approach. Architectural elements, sculpture, fountains, ponds, walls, grottoes, and gardens adorned the site—some miniaturized and others monumental; his choices of images, narratives, and “lessons” were intended to be at once educational and entertaining.

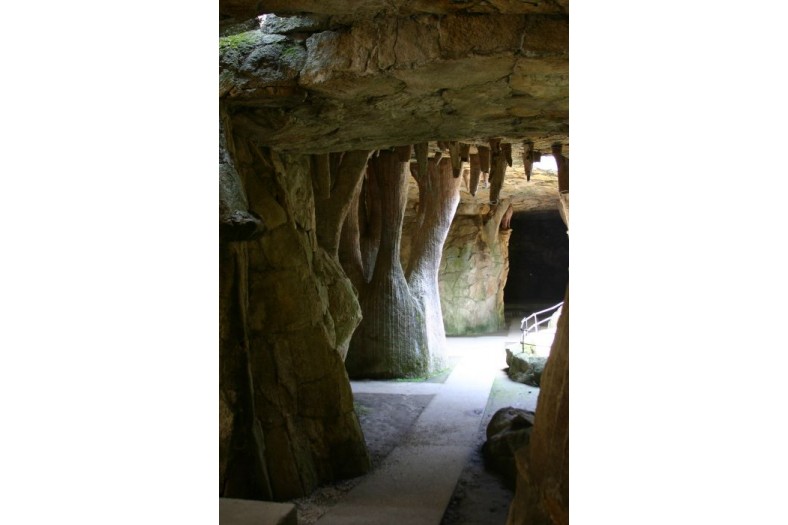

Design of such architectural elements as walls, walkways, and banisters tended to be in the style borrowed from the assortment of architectural idioms being explored in the Americas, rather capriciously combined with elements of indigenous architectural traditions, resulting in an eccentric and fanciful display. Certain whimsical ornamental components found in O Pasatempo are also extant in other gardens built during this time period, such as the ornamental use of shells, murals, and mosaics; tree trunks represented in concrete (both as supports and serving a purely decorative function); and artificial grottoes with stalactites and stalagmites. It appears that the murals, sculptures, fountains, or grottoes were developed on a rather ad-hoc, additive basis, rather than being planned out and preconceived as a totality in advance, although it was visualized from the beginning as an encyclopedic park.

The decline of the Park began immediately following Juan’s death. Unfortunately, he had not specified funding for the Park in his will, and with the worldwide economic crisis, the value of the family’s holdings dropped precipitously. Left with few resourses, the heirs began to sell off pieces of the land; worse, during the Civil War, the Nationalist forces took over the Park and used it as a concentration camp for hundreds of Republican prisoners, using the statues and busts as targets for shooting practice. Relatives of García Naveira tried to save some of the other sculptures, moving them off-site for protection. But as the Civil War concluded, leading to the Years of Hunger in the 1940s, desperate and starving unemployed locals ripped out the steel infrastructures and lead pipes that had given form and provided water to the various bas-reliefs, sculptures, fountains, and ponds, selling them off to buy bread.

Finally, after close to fifty years of increasing deterioration and general abandonment, in 1980 a local movement began to try to recover what was left of the Park with the intent to promote it as part of the artistic patrimony of the area. The gardens and Park were purchased by the municipality of Betanzos in 1986 and, following general stabilization, a thorough and rigorous review of oral testimonies, historical photographic images, new aerial photographs, and physical research in situ, they were able to create a registry of extant, damaged, or missing elements, and to prioritize both the replacement of elements no longer extant that they felt were crucial to the pedagogical, historical, entertainment, aesthetic, and enigmatic nature of the Park, as well as the conservation of existing elements and the addition of new park amenities (bathrooms, benches, etc.). Unfortunately, among the positive results of clearing weeds, cleaning, and restoration of parts of the Park and gardens, were also ill-conceived additions such as the large, modern cement and glass auditorium perched on the highest level of the Park, dominating the lookout over the city.

Nevertheless, a visit to O Pasatempo today, although covering only ten percent of its former acreage, and displaying an even smaller percentage of its former glory, is still an impressive, educational, and entertaining experience. With time compressed to encompass a variety of historical styles, and space compressed to include images and objects referencing a universe of knowledge, the Park interlaces art, gardens, architecture, and mystery.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2013

Update, January 2020: According to this La Voz de Galicia article, the city of Betanzos has started conservation work on O Pasatempo.

Contributors

Map & Site Information

17 Praza Alfonso IX, 15319

es

Latitude/Longitude: 43.2790823 / -8.2128946

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.