Museo de ManManfred Gnädinger (1936 - 2002)

About the Artist/Site

The Gallegan Coast of Death is treacherous and stormy, yet in 1961 it became the refuge for a German teacher not markedly different from other young bourgeoisie who traveled to the far corners of the earth to find a simpler, more “authentic” and tranquil existence. He fell in love with a local teacher, and when she married another, he renounced his passport and “normal” way of life, grew a beard, became a hermit, and refused thereafter to use any part of his name except for “Man.” He regularly swam long distances in the frigid waters, became a vegetarian and wore only a loincloth despite the generally cool and rainy temperatures. Soon he began to construct a “museum” here near the end of the earth (Finisterre). His building blocks were the rocks smoothed by the crashing waves as well as the bones of beached animals, seaweed, and other detritus thrown up from the sea, and he arranged and assembled them with a mixture of cement and local vegetation. He lived at one with the sea in this inhospitable but strikingly picturesque spot until 2002, when the nearby shipwreck of the tanker Prestige spilled 77,000 tons of oil, contaminating the coasts of Spain, Portugal, and France, killing innumerable fish and wildlife, and coating everything with the toxic slick. It is said that he died that next month of a broken heart.

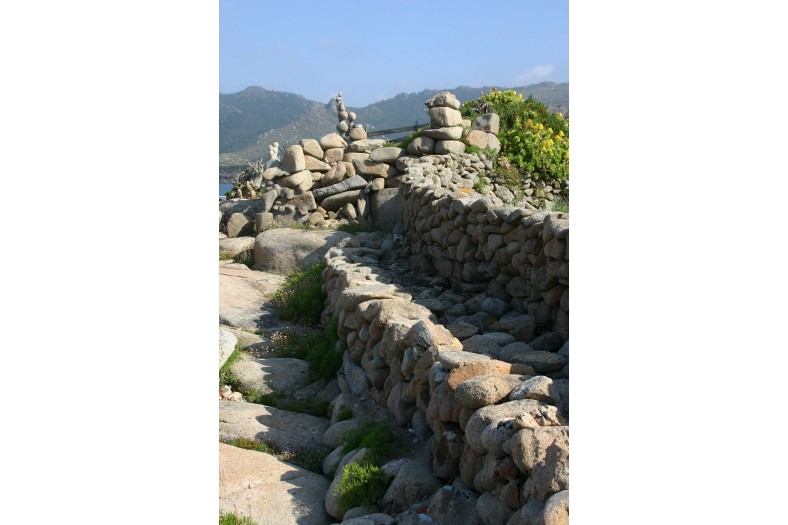

Political wrangling has prevented any comprehensive conservation of the site, although a cultural center built in the artist's name has been constructed near the dike. Remnants of the site are still viewable, but little of the artist's oeuvre is still extant.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2013

----------------------------------------------------------------------

It was a voyage without return, resulting in Manfred Gnädinger’s (1936-2002) arrival at the Costa da Morte, in Galicia, Spain, in the spring of 1961. At that time he was just a young German with artistic inclinations and pacifist and environmental ideas, far from imagining the direction his life would ultimately take in the small fishing village of Camelle. His arrival began forty-one years of transmutation, freedom, and emotional exchange with nature: his work would become a natural entity, indissolubly linked to the sea and to the life cycle of the earth, where the element of the circle would constitute the beginning and also the end, inspiring decades of turning his life into an endless happening, as he merged his art with his everyday life.

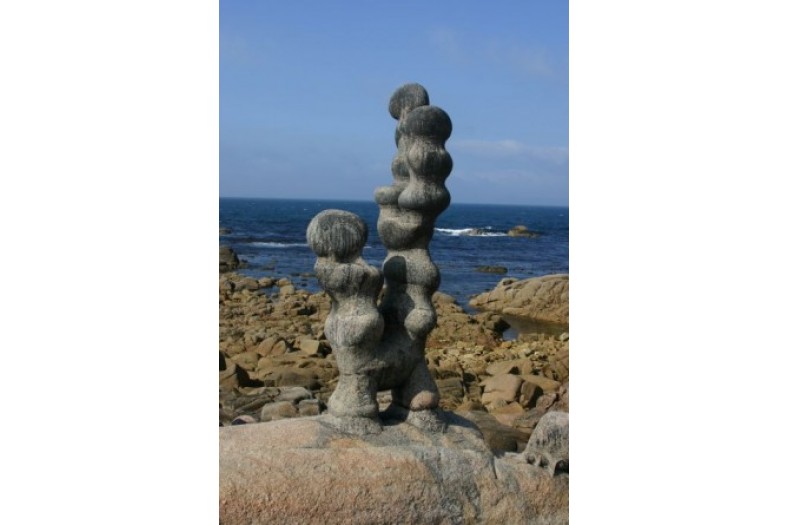

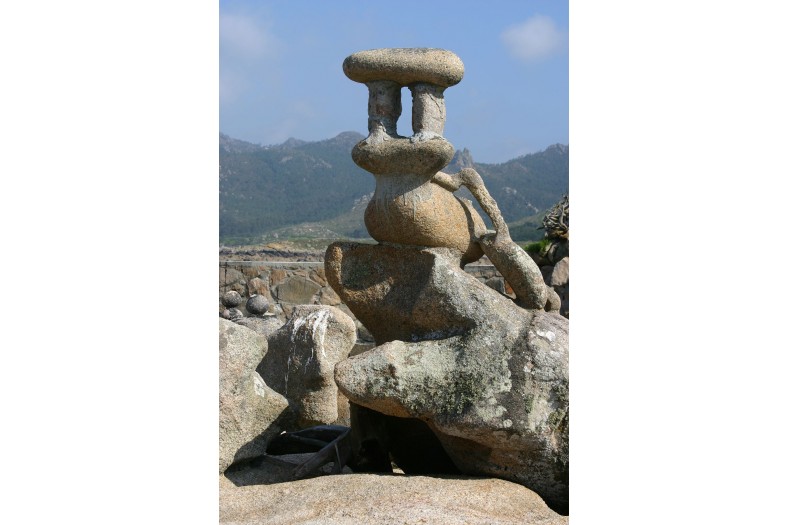

From the moment that Gnädinger decided to burn his personal documents, he left behind a past of social conventions in order to build a new environment of visual representations: his Museum. From then on, he would be known as Man, or El Alemán de Camelle. Everything he saw upon awakening each day became the basis for transformation into an artistic object. Little by little he amassed a unique body of work integrated by debris washed ashore by the sea; rocks, which he used in his garden of fantastic sculptures; found roots and debris of all kinds; his tiny shed, with just enough room to live; artistic interventions around the bay’s pier; art installations of various types and forms; paintings, drawings, and photographs. This transformation ultimately included his own image, as he abandoned clothes and deconstructed himself into the simplicity of nakedness, stripped of all material ties in an honest, intuitive, and experimental gesture. By using his body as an element of interaction with the medium, sensitive to its signs and signals, he reaffirmed the character of his artistic work: a long ritual always in process, which would assume a status comparable to a philosophy of life or religion.

The same constant simplicity in his works and actions is marked by a fine line that shows the individual in his purest state, in open dialogue with natural phenomena, and especially with the sea. This liaison was so strong that he decided to build his Museum on the shores of the town’s bay entrance, and he came to feel and call himself the son of Neptune, born from a wave. The sea as center, as protagonist of unusual, disturbing elements and, often, a powerful scene of death, but also as a source of reflection: in the sea, the artist found the inspiration to emerge with a unique worldview based on the self-referential: his personal experience, of encounter and survival, would trace the coordinates of an interior landscape based on the synthesis of circular forms.

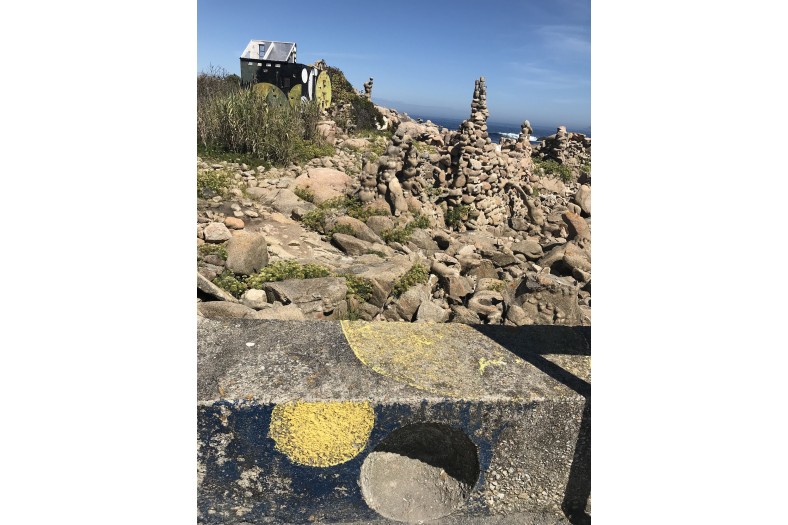

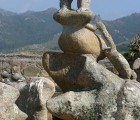

In the circle, Man found his greatest expression: a leitmotif translated into a vocabulary at once abstract and direct. The circle summed up an obsessive but sober aesthetic, minimal in resources; of a geometric organization based on a complex thought, and guided only by the impulse of creation. The artist covered his whole house with sets of circles of chromatic contrasts, from the floor to the walls. The circular shapes determined the assemblages and sculptures of the garden or the installations that he realized with old mirrors; he painted the rocks of the tempestuous surroundings, the façades of some houses, and the almost three hundred and eighty meters of built pier with circles. This pier once divided Man’s Museum, but later became an extension of it, as he covered it with compositions of large scale, sculptures from recycled and found objects, and even, debossed in freshly poured concrete, the contour of his body, as a protest against the pier’s expansion.

The ephemeral character of those works, exposed to the natural and hostile environment, provided the artist with a circular and infinite dynamic, which motivated him to the repetitive and incessant action of remaking them again and again. This cyclical emphasis may have influenced the rhythm and poetic accent of his aphorisms and other metaphorical texts, which Man wrote as reflexive and theoretical exercises. In one of his aphorisms about the circle he commented: "The point, zero space. The nothing. By contrast the circle with dimension. If the nothing reaches me, I cease to exist. If the center of my circle reaches me, I am all present."[1]

In a radio interview with Man in 1986, the artist commented on the codes of the circle in his work, and the relationship of this with the sea, and his person:

My soul is nothing but the circle, and if the circle is deformed then it is the wave, the wave, and I am like that, without body, without anything, only free, like this, and I am water, nothing more (...); the circle is the element of the world, there is only the circle; it is the origin of other elements; the circle thus is all in three dimensions or more, if they exist. The line is also inside the circle, and the horizontal line, as we look at the sea, is a line. But for the long line, the long circle is the earth; and thus, circulation, circulation of the universe, is a whole circle, all circles; and if it is square, then it is a circle of four points (...); and thus the triangle is a circle of three points (...); the circle is softer and round like the body (...)[2]

One detail to consider in Man's work was his voluntary isolation. He had only a handful of friends, and he preferred to maintain the bond with his family by postal correspondence. The artist considered solitude as his “multiplication table,” as an intimate monologue and modus vivendi; his loneliness was conditioned by cultural contradictions with the social environment that surrounded him. This is something that often happens when self-taught artists decide to break with conventional schema and breach behaviors generally accepted by society. However, despite this isolation, people who visited his Museum from all over Spain and around the world became an active part of his artistic practice. He provided them with small notebooks, and they interacted with the artist by drawing and leaving their impressions for him. Over a period of decades, Man gathered thousands of notebooks, all imprinted with the experiences of this participatory action; today they are conserved as an integral part of his own work. The artistic process moved, in this case, from his individual work to that of the public, and vice-versa, in continuous feedback, where public participation became a primary factor in his continuing production.

In addition to the monumental paintings of large circles, the small house and the stone sculpture garden were fascinating to those who visited the Museum.[3] The whole complex was a site specific work in constant evolution. The cozy, wood, brick, and glass shed measured barely thirteen square meters; in it he kept his books of art and philosophy; catalogs; tools and materials; notebooks, duly ordered by date; manipulated books; installations and sculptural works of bones, snails, shells, corals and plastic; and photographs, drawings on paper, and paintings on canvas. The house had a functional design with a marked artistic intention, a result of its color, the figures of circles in the interior and exterior, the solarium of almost three square meters, and the rhythmic arrangement of the fifty-some openings of various sizes. Too, the door was an important element, as it projected the light by day and by night; the structure and location of the house surely responded to a meticulous study of the light, of the cardinal points, and of the climate of that coastal geography. As for the sculptures in the garden, he manually moved each stone, then glued them with cement. He created a whimsical grouping near the shed, some in the form of pinnacles, fountains, porches, or gigantic temples. He considered each stone a “silent word,” which, taken together, formed aphorisms. They were pure visual poetry, staged in the silence of the loneliness of an artist who built his ideal home, his refuge, to escape from the world. His decades of artworks were all he had, and he loved them as a father loves his children.

That's why it was such a hard blow, when, on a morning in November 2002, day dawned with his Museum covered with a thick layer of oil. A ship had capsized in the middle of the storm, spilling seventy-seven thousand tons of oil into the sea. With the black tide caused by the Prestige, not only a good part of the Galician coastlines were ruined, but also the work of a lifetime of this prolific artist. The sadness, grief and disappointment so drowned Man's heart that, without strength left, he died at age 66, a month after this terrible disaster.

During all that time of spiritual surrender and effort, there were those who considered him a lazy fool; others saw him as a genius or a fortune-teller capable of predicting the future. But Man was nothing more than an artist who had seized the full freedom to create, and who assumed, as few have, the risk of anonymity, by developing his productions in a place apart from artistic circuits: away from galleries, fairs, collectors, critics, auctions and events. This risk was, at the same time, his work’s greatest merit. With his isolation, he avoided environments contaminated by markets and social pressures, enabling him to create an artistic work in communion only with himself, and to consolidate a coherent body of work merging its different manifestations under the premise of demonstrating the real possibility of establishing a link between art and life. Man surged in through experimentation and the search for himself; managing to blur classifying boundaries that enclose or frame trends, movements and periods; and becoming the necessary link in understanding the creative process, as a broad cycle, without limits, beginning or end.

~Yaysis Ojeda Becerra

Art researcher and critic

Madrid, October 28, 2018

[1] Manfred Gnädinger. Unpublished documents, courtesy Museo Man de Camelle: nd.

[2] Mandred Gnädinger, quoted in interview on Radio Televisión Galicia: 1986.

[3] Jo Farb Hernández, curator and researcher into spaces of architecture and art brut, and director of SPACES – Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, dedicated chapter forty of her book Singular Spaces: From the Eccentric to the Extraordinary in Spanish Art Environments (Editorial Raw Vision, 2013) to the work and museum of Man, the German of Camelle.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Los Círculos de Man

“Vida es círculo. Vida es circunstancia, circunferencia, circulación”

~Man

Fueron las circunstancias de un viaje sin regreso, lo que propició que en la primavera de 1961 llegara Manfred Gnädinger (1936-2002) a la Costa da Morte, en Galicia, España. En aquel momento era solo un joven alemán con inclinaciones artísticas e ideas pacifistas y medioambientalistas, que lejos estaba de imaginar el rumbo que tomaría, en el pequeño pueblo pesquero de Camelle. Cuarenta y un años de transmutación, de libertad e intercambio emocional con la naturaleza: el sujeto cual ente natural, indisolublemente ligado al mar, al ciclo vital de la tierra; donde el elemento del círculo constituiría el principio y también el fin, en décadas de convertir su vida en un happening interminable, al comulgar el arte a su cotidianeidad.

Desde el instante que Manfred decidió quemar sus documentos personales, dejó atrás un pasado de convencionalismos sociales, para construirse un nuevo entorno de representaciones visuales: su Museo. A partir de entonces, se le conocería como Man o El Alemán de Camelle: y todo lo que su vista alcanzaba al levantarse, lo fue transformando de a poco en objeto artístico. Hasta conformar una única obra integrada por los desechos del mar, las fantásticas esculturas en piedra de su jardín, la diminuta caseta con lo justo para vivir, las acciones plásticas en el dique, las instalaciones, las pinturas, dibujos y fotografías. Transformación que incluiría su propia imagen, al abandonar las ropas y deconstruirse en la simplicidad de la desnudez, despojado de ataduras materiales, en franco gesto performático, instintivo y experimental. Con el uso del cuerpo como elemento de interacción con el medio, sensible a sus signos y señales, reafirmaba el carácter procesual del hecho artístico, en un largo ritual que asumiría cual filosofía de vida o religión.

La misma simplicidad constante en sus obras y acciones, marcada por esa delicada línea que mostraba al individuo en su estadio más puro; en diálogo abierto con los fenómenos de la naturaleza, y en especial con el mar. De tal modo que decidiera construir su Museo a orillas de este y llegara a sentirse hijo de Neptuno, nacido de una ola. El mar como centro, protagonista de lo inusitado, elemento perturbador y de poder, escenario de muertes y fuente de reflexiones; en el mar, el artista encontró el motivo para emerger con una particular cosmovisión afincada en lo autorreferencial; su experiencia personal, de encuentro y sobrevivencia, trazaría las coordenadas de un paisaje interior asentado en la síntesis de las formas circulares.

En el círculo Man encontró su máxima expresión, un leit motiv traducido en lenguaje abstracto y al mismo tiempo directo. El círculo resumía una estética obsesiva pero sobria, mínima en recursos; de una organicidad geométrica sustentada en un pensamiento complejo, y guiada únicamente por el impulso de la creación. Con juegos de círculos de contrastes cromáticos, el artista cubría toda su caseta, del suelo a las paredes. Las formas circulares determinaban los ensamblajes de las esculturas del jardín o las instalaciones que realizaba con antiguos espejos; con círculos pintaba las rocas del entorno abrupto, el muelle en el pueblo, las fachadas de algunas casas; y los casi trescientos ochenta metros de dique que una vez dividieron su Museo, para después convertirse en una extensión del mismo, al quedar cubiertos por composiciones a gran escala, esculturas con elementos de reciclaje, o dejar plasmadas las huellas de su cuerpo sobre el cemento fresco -a manera de protesta- cuando empezaban a construirlo.

Es posible afirmar que el carácter efímero de aquellas obra expuestas al medio natural y hostil, le generaran al artista una dinámica circular e infinita, que lo obligaban a la acción repetitiva e incesante de rehacerlas una y otra vez. Ese énfasis cíclico, pudo haber influido en el ritmo de los aforismos de acento poético y otros textos metafóricos, que Man solía escribir cual ejercicios reflexivos y teóricos. En uno de sus aforismos sobre el círculo comentaba: “El punto, espacio cero. La nada. Por contraste, el círculo con dimensión. Si me alcanza la nada, dejo de existir. Si me llega el centro de mi círculo, soy todo presente.”[1]

Luego, en una entrevista radial, realizada a Man en 1986, el artista comentaba sobre los códigos del círculo en su obra, y la relación de este con el mar, y su persona:

“Mi alma es nada más que el círculo, y si es jorobado el círculo pues es la ola, la onda, y soy así, sin cuerpo, sin nada, solamente libre así, y soy agua nada más (…)El círculo es el elemento del mundo, no existe más que el círculo. Es el origen de otros elementos. El círculo así es todo, en tres dimensiones o más, si existen. La recta también está dentro del círculo. La horizontal cuando miramos ahora al mar es una recta, pero por la larga no, por la larga es el círculo de la tierra; y así, circulación, circulación del universo, es todo un círculo, todos círculos; y si es cuadrado pues es un círculo de cuatro puntos (…); y así el triángulo, es un círculo de tres puntos (…); el círculo es más suave y redondo como el cuerpo (…)"[2]

Un detalle a considerar en la obra de Man, fue su aislamiento voluntario. Apenas contaba con un puñado de amigos; y prefería mantener el vínculo con su familia por correspondencia postal. El artista consideraba la soledad como su tabla de multiplicar, de monólogo íntimo y modus vivendis. Soledad, que pudo estar condicionada por las contradicciones culturales con el entorno social que le rodeaba. Algo que suele ocurrir frecuentemente con los artistas outsiders, cuando deciden romper con esquemas y salirse de las conductas aceptadas por la sociedad. Aunque a pesar de este aislamiento, las personas que visitaban su Museo desde varios lugares de España y del mundo, formaban parte activa de este, al interactuar con el artista mediante pequeñas agendas que Man les ofrecía, para que dibujaran y dejaran sus impresiones. Por años, el artista logró reunir miles de agendas que recogían las experiencias de esta acción participativa, y que hoy se conservan como parte integral de su propia obra. El proceso artístico se movía en este caso, de la obra al público y viceversa, en una continua retroalimentación; donde la participación del público se convertía en un factor primordial.

Al igual que las pinturas monumentales con los grandes círculos, la caseta y el jardín de esculturas en piedras, eran la fascinación de quienes visitaban el Museo. [3] Todo el complejo resultaba un site specific en constante evolución. La acogedora caseta de madera, ladrillo y cristal apenas medía trece metros cuadrados; en ella conservaba sus libros de arte y filosofía, catálogos, herramientas y materiales, las agendas debidamente ordenadas por fecha, cuadernos de apuntes, libros manipulados, instalaciones y piezas escultóricas de huesos, caracoles, conchas, corales y plástico; además de fotografías, dibujos sobre papel y pinturas sobre lienzo. La caseta poseía un diseño funcional con una marcada intención artística, dada por el colorido, las figuras de círculos en el interior y en el exterior, el solárium de casi tres metros cuadrados, o la disposición rítmica de las alrededor de cincuenta ventanas de diversos tamaños y la puerta, que proyectaban la luz de día y de noche; con seguridad, la estructura y ubicación de la caseta respondía a un estudio minucioso de la luz, los puntos cardinales y el clima de esa geografía costera. En cuanto a las esculturas del jardín, movía manualmente cada piedra, para luego pegarlas con cemento y crear un conjunto caprichoso cerca de la caseta; algunas en forma de pináculos, fuentes, pórticos, o gigantescos templos. Consideraba cada piedra como una palabra sin ruido, que unidas formaban aforismos. Pura poesía visual, escenificada en el silencio de la soledad de un artista que construyó su hogar ideal, su refugio para escapar del mundo. Sus obras de décadas de trabajo eran todo lo que tenía, y las amaba como un padre a sus hijos.

De ahí que fuera un golpe tan duro, cuando en una mañana de noviembre del 2002, su Museo amaneciera cubierto de chapapote. Un barco había colapsado en medio de la tormenta, derramando al mar las setenta y siete mil toneladas de petróleo que traía. Con la marea negra provocada por el Prestige, no solo quedaron desbastadas buena parte de las costas gallegas, sino la obra de toda una vida de este prolifero artista. La tristeza, la pena y la desilusión ahogaron el corazón de Man, ya sin fuerzas; quien murió a los 66 años, al mes siguiente de este terrible desastre.

Durante todo ese tiempo de entrega espirituay esfuerzo, hubo quienes lo tenían por un loco y un vago; en cambio otros lo veían como un genio, o adivino capaz de predecir sucesos. Pero Man no era más que un artista en plena libertad de crear, que asumió como pocos el riesgo del anonimato, al desarrollar sus producciones en un lugar apartado de los circuitos artísticos; lejos de galerías, ferias, coleccionistas, críticos, subastas y eventos. Riesgo que a la vez resultó su mayor mérito. Con su aislamiento, se mantuvo fuera de ambientes contaminados por el mercado y presiones sociales, para realizar una obra artística en comunión consigo mismo; y consolidar un cuerpo coherente, donde se fusionaron las distintas manifestaciones, bajo la premisa de demostrar la posibilidad real de establecer un enlace entre el arte y la vida. Man irrumpe desde la experimentación y la búsqueda de su yo; logra difuminar fronteras clasificatorias que lo encierren o enmarquen en tendencias, movimientos y períodos; y se convierte en el eslabón necesario para entender el proceso creativo, como un amplio ciclo, sin límites, principio ni fin.

~Yaysis Ojeda Becerra

Investigadora y crítica de Arte

[1] Manfred Gnädinger. Documentos inéditos, cortesía Museo Man de Camelle, sin fecha.

[2] Manfred Gnädinger, citado de una entrevista de Radio Televisión Galicia: 1986.

[3] La comisaria e investigadora de arquitecturas y espacios bruts, Jo Farb Hernández, también directora de SPACES – Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, dedicó el capítulo 40,de su libro Singular Spaces: From the Eccentric to the Extraordinary in Spanish Art Environments (Editorial Raw Vision, 2015) al Museo Man el Alemán de Camelle.

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Camelle, Galicia, 15121

es

Latitude/Longitude: 43.1828201 / -9.0923614

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.