Mollie Jenson's Art ExhibitMollie Jenson (1973)

Non Extant

River Falls, Wisconsin, 54022, United States

late 1930s - mid 1950s

About the Artist/Site

Mollie Nelson was born on a farm that had been settled by her Norwegian grandfather in rural River Falls, WI, about 20 miles east of the Mississippi River. In 1911 she married Obert Jenson, and the two began their farm and family life together, raising six children, as well as crops and cattle, on the land she inherited from her family. At the time, the expectations for Midwestern farm women were clear-cut and strongly reinforced by social customs and religious mores: work, husband, family, farm, church, and work, all centrifugally centered around the home. Jenson had a subtle edge on the system, however, for the Jensons’ land came from her own family. Jenson satisfied the usual expectations and then went on to satisfy grand ones of her own.

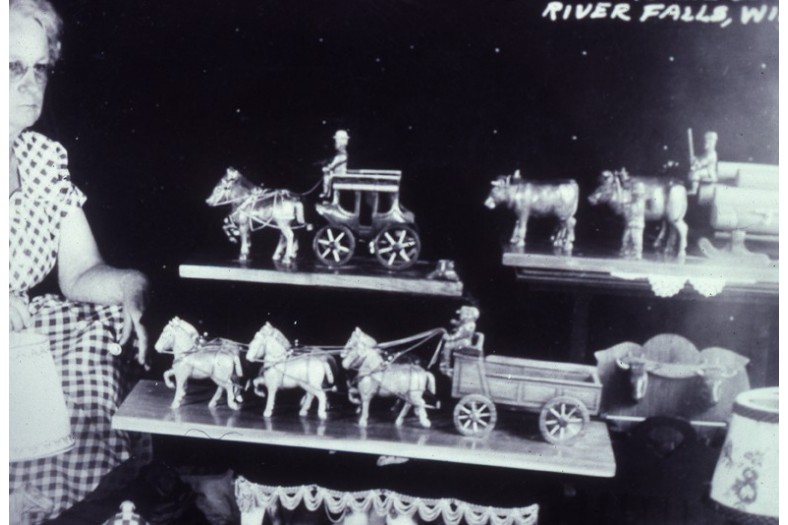

Mrs. Jenson had a reputation for being strong-willed, fiercely independent, and endlessly creative and busy. She pursued the proper activities for farm women at the time, making “fancy work” such as hooked rugs and quilts. She made drawings and paintings, and enjoyed cooking, “especially fancy dishes.” Moving beyond the conventional “polite arts” for women, she also made horn furniture and wood carvings, primarily of horse teams pulling wagons. On the only vacation she and Obert ever took, she brought her carving along with her. Butternut wood shavings fell to the floor, apparently creating quite a stir, as she whittled away on the train.

Jenson loved animals and had a rapport with them that apparently outweighed her affinity for people. In about 1938, when she was forty-eight, the gradually increasing collection of Jenson pets grew into an impressive, unusual country zoo. The fluctuating menagerie featured twenty-six species and over 150 different animals at one time or another, including badgers, opossum, raccoons, a selection of monkeys, exotic squirrels, coyotes, foxes, peacocks, a snowy owl, pheasants, woodchucks, ferrets, parrots and fancy fowl, a few black bears, and a lion. Regional zoos and circuses knew of Mollie’s generous spirit and patience with animals and left her with more than a few imperfect specimens. For example, an infamous six-foot-tall black bear named Ma, who had lost a paw in an auto accident and could no longer ride a bicycle in the circus, was retired to the Jenson zoo. Ma loved riding in Jenson’s son Harold’s car and especially enjoyed their visits to local taverns, where she guzzled bottles of beer, dropping the empty ones to smash on the brass rail below. Most of the animals stayed in their cages, however, and for the twenty or so years that the zoo existed it attracted countless people. On Sunday afternoons in the warmer months, anywhere from one to five hundred tourists wandered the Jenson property.

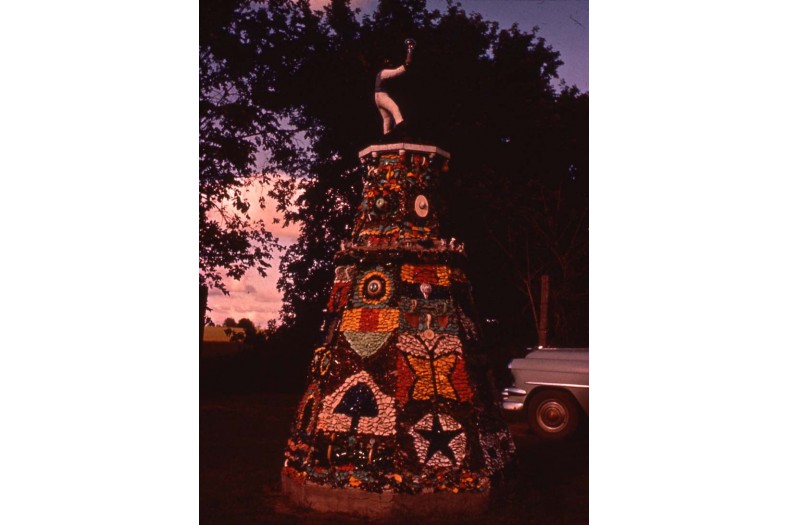

In the late 1930s Jenson began building a sculpture garden. Fueled by her inexhaustible capacity for hard work (and assisted by a ready work force—her children), Jenson’s innate sculptural abilities and her strong sense for color, composition, and the surrounding landscape flourished in a garden of sculptural and architectural forms—introducing an element of formality to complement the more prosaic structures of the zoo. She began with a rock garden, fish ponds, and lily pool, which she built with an interesting variety of local limestone. In the summer of 1940 she completed her first “edifice” (a Jenson family term) of embellished concrete. Exploding a common yard ornament beyond its miniature and ordinary form, Jenson’s Dutch Windmill was about ten feet tall—a kaleidoscopic monument of shapes and images made primarily from solid color fragments of china and glass. Perhaps owing to her familiarity with hooked rug and quilt design and her facility with traditional textile techniques, Jenson’s surface ornamentation resembled patchwork fabric. Like her other textile projects, Jenson composed her designs on the living-room floor at night, using shards of crockery that she broke in the bathtub. Block forms of color outlining simple images adorned the windmill base: star, horseshoe, mushroom, butterfly, pine tree, crescent moon, rainbow, owl, arch-backed cat, dog. The upper rim of the windmill was illuminated with bright-colored light bulbs; the top was surmounted, oddly enough, with a commercially made “step-’n-fetch-it” African American jockey figure holding a light bulb, counterbalanced by vanes that caught the winds and powered the lights.

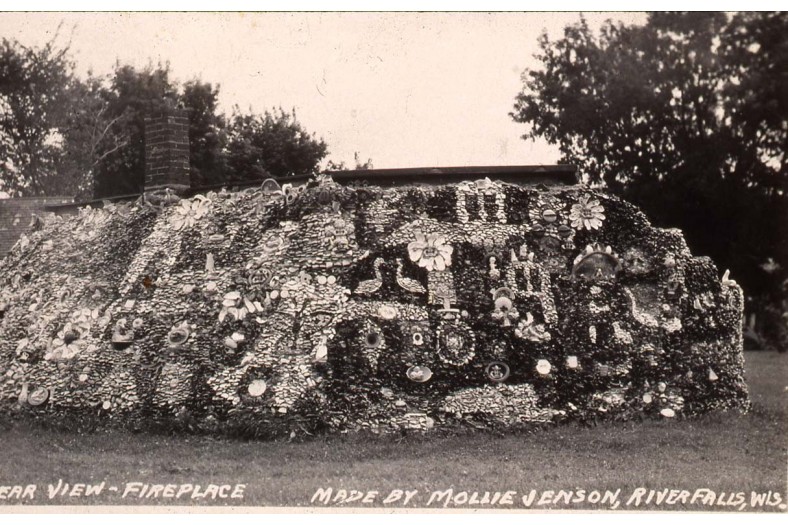

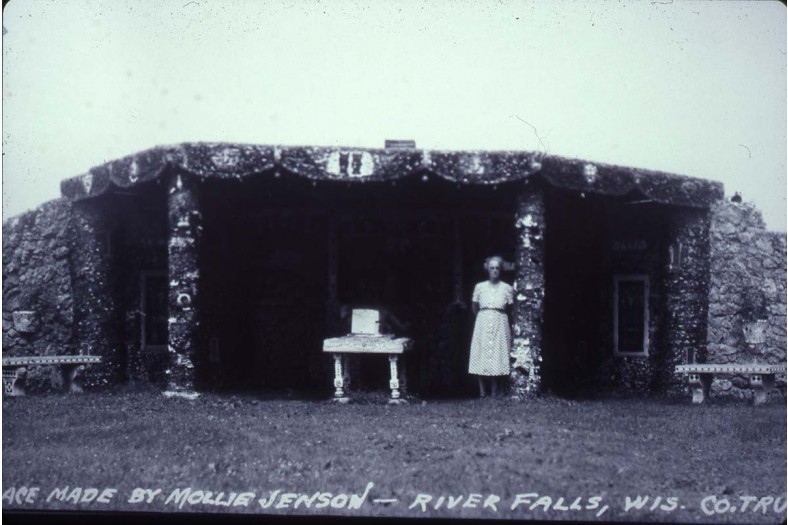

Her next venture started with a simple plan for a yard-improvement project and developed into a monumental, highly original structure, Jenson’s Fireplace. “I had an old barn that was hit by lightning. It burned down and the rocks from its foundations lay in the grass until I got sick of them. I rolled them into the yard to make a fireplace. From there one thing led to another. I knew a woman in Martell who took in washing and she had a lot of Hilex [bleach] bottles. So I got them, broke them up and started building.” The Fireplace had two distinct sides. The interior was a sheltered concave space: four pillars supported a canopy roof with an elaborate valence; a pair of black glass owls adorned the center of this encrusted concrete drapery. The actual fireplace—a relatively small hearth—was centered in the interior, with a deer trophy above. Recessed shelves held taxidermy mounts and carvings. Jenson incorporated false window shapes into the interior walls, and an encrusted table and benches completed the illusion of a stage-set living room. The consistent allusion to fabric in form and design, and the sense for domestic space that her structures elicit, lent a distinctly feminine feeling to her work. The “edifice” was made with Rush River hills limestone, rocks from the hills near Fountain City, red granite, mica flakes “as big as your thumb,” panels of exotic rock, tile, broken blue bottles, ceramic shards from the Red Wing Pottery, and other miscellaneous materials. Jenson incorporated her name and the year it was completed, 1941, into the wall.

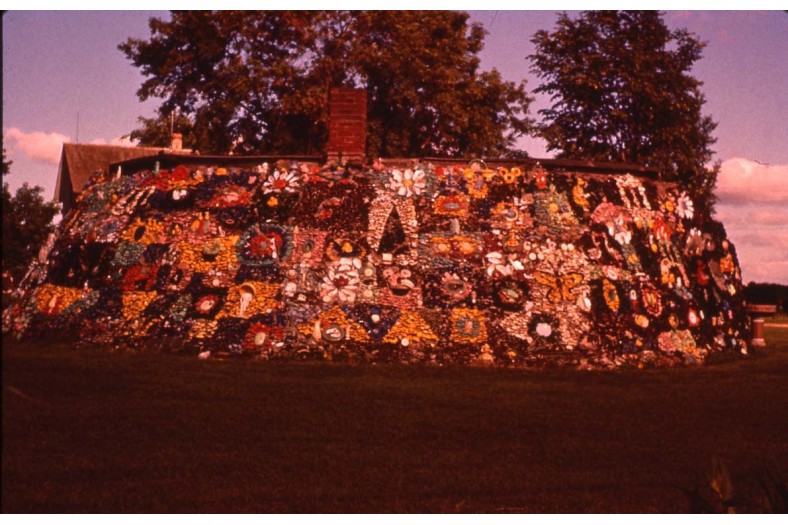

Each time Jenson thought she was finished with the Fireplace she perceived a missing element and continued to build. She decided that it needed sides. The sides were then extended into the rear—an enormous convex surface, loosely resembling the mountain forms of Father Dobberstein’s small grottos. (Although a relationship to the regional grotto phenomena may or may not have been intentional, a 1952 news article describing the Fireplace referred to this work as a grotto and related that “elsewhere on the grounds Mrs. Jenson is building a grotto.”) The west face of the Fireplace was an eye-dazzling curtain wall of embellished-concrete. Illuminated at night, the Fireplace was the focal point for many picnics and parties, about which Harold recalled fondly, “they’d drink too much and fall against the glass!”

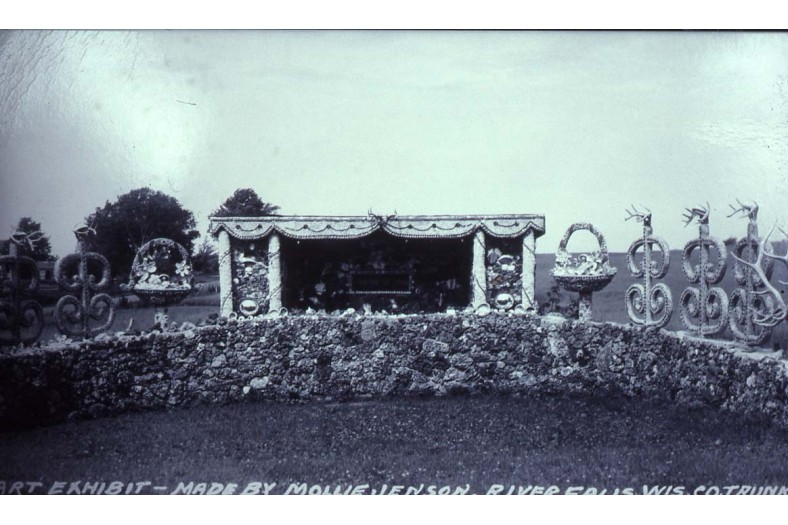

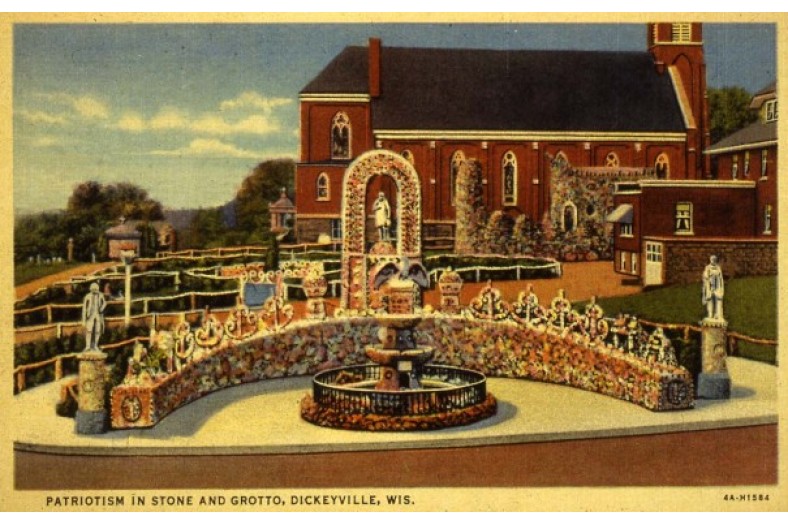

The design for Jenson’s next structure was a near-replica of the Patriotism Shrine at the Dickeyville Grotto. A gently curved rock wall was surmounted by anchor forms of embellished concrete. This structure, called the Horseshoe, had a diorama in the center. Like the Fireplace, the roof over this little shelter was finished off with a valence and supported by columns, and the diorama was flanked with embellished concrete flower baskets.

Jenson’s children recalled being required to labor on their mother’s “edifices,” building structural forms, mixing concrete, and joining in the “commotion out there at flower planting time.” Their father Obert was busy with the farm and thought the Art Exhibit and zoo were “foolishness,” though he, too, assisted over the years. The Jenson zoo finally closed in 1959. Shortly after, Jenson moved to town to live with a daughter, leaving the “home place” in the care of one of her sons. But the Art Exhibit began to deteriorate, and Mollie died in 1973. In the late 1970s, family members felt that structures of broken glass posed a threat to children’s safety, and all the structures, with the exception of the Dutch Windmill, were demolished.

Known to the public as Mollie Jenson’s Art Exhibit, elements of sculpture, architecture, landscape, and museum were cultivated and intermingled in an ingenious extension of home and farm culture, all adjacent to a vernacular farm house and her small but ambitious zoo. While we were conducting this research in 1993, Jenson’s grandson, Don Blegen, was pleased that we took interest in Grandma Jenson, saying “She was an extraordinary woman; and the older I get, the more I realize just how remarkable she really was. When I was a little boy, playing hide-and-seek on summer Sunday evenings around those marvelous concrete-and-glass constructions with my brothers and cousins, or helping Grandma feed the animals, or just lost in fascination watching the monkeys (or watching the Sunday visitors react TO the monkeys)—when I was just doing all of that, I just accepted it for what it IS. It has taken years to appreciate just how privileged I was to be Mollie Jenson’s grandson and to have such experiences enriching my childhood. Here was a woman who did it all, years before emancipated women were discussed in the opinion pages. She took care of her obligations as a farmwife, raised six children, built up a menagerie of animals and took loving care of them, found time for her multidisciplinary creative work, and orchestrated it all with a CEO’s hardheaded business sense. In the Forties! God bless her, she juggled it all with grace and panache, and nobody who writes on the op-ed pages ever heard of her.”

~Lisa Stone and Jim Zanzi

Materials

Embellished concrete, found objects

Map & Site Information

River Falls, Wisconsin, 54022

us

Latitude/Longitude: 44.861356 / -92.623808

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.