Stella Waitzkin's Chelsea Hotel ApartmentStella Waitzkin (1920 - 2003)

Relocated (incl. Museums)

222 W. 23rd St. , New York, NY, 10011, United States

1969–2003

Waitzin's work is held in collections all over the United States. Several of the "walls" of her Chelsea Hotel apartment are installed at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center's Art Preserve in Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

About the Artist/Site

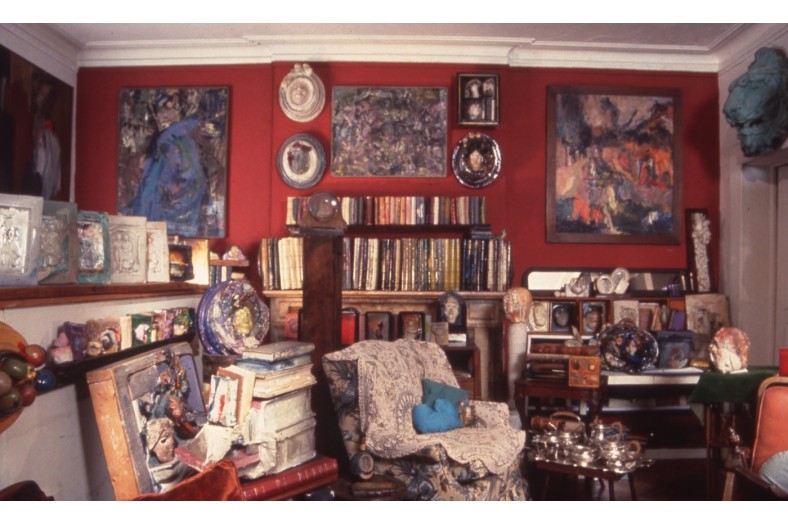

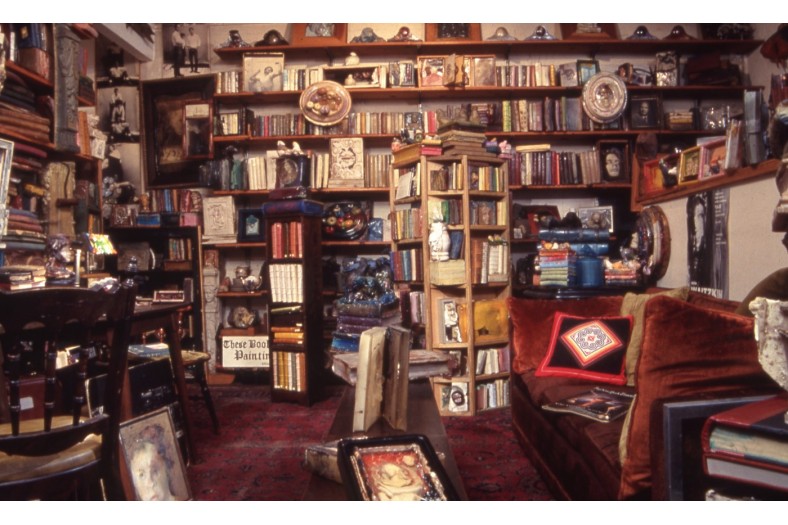

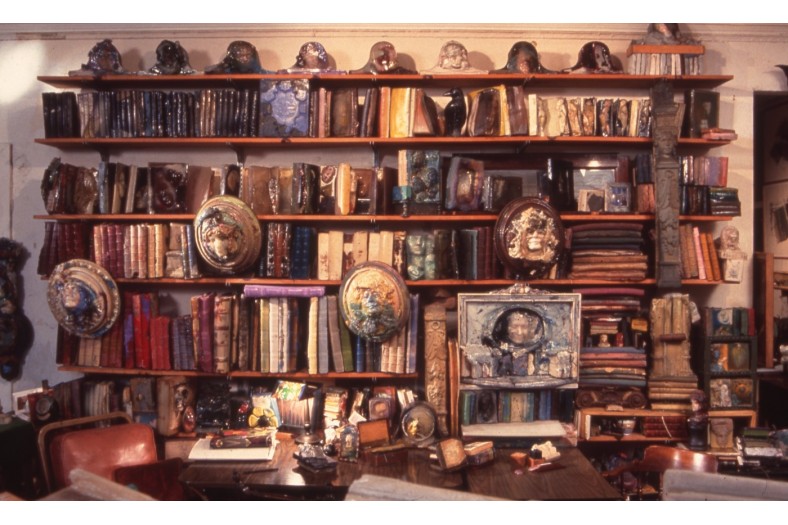

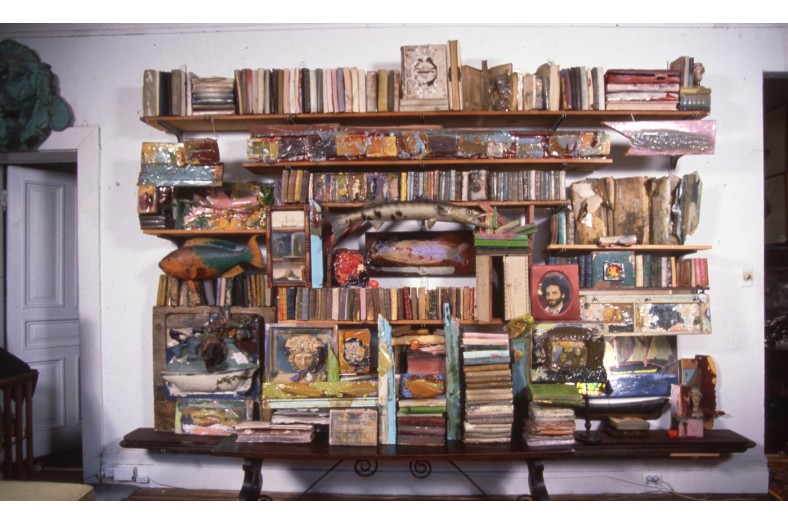

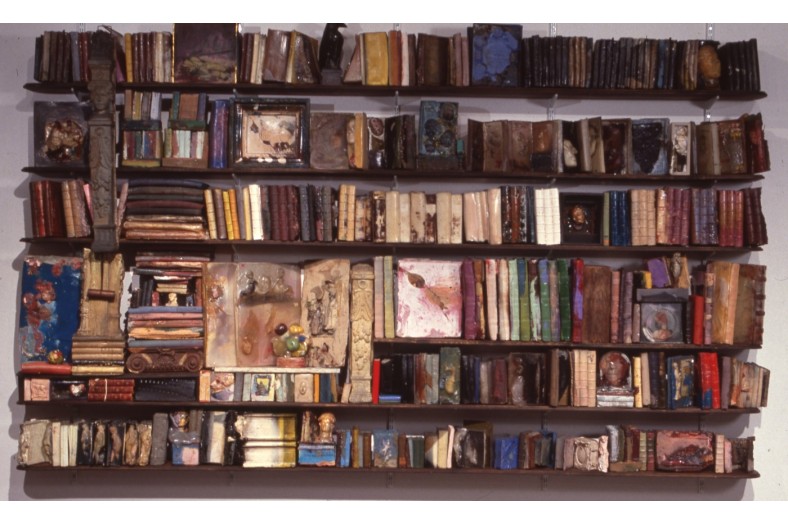

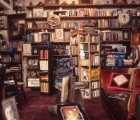

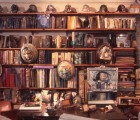

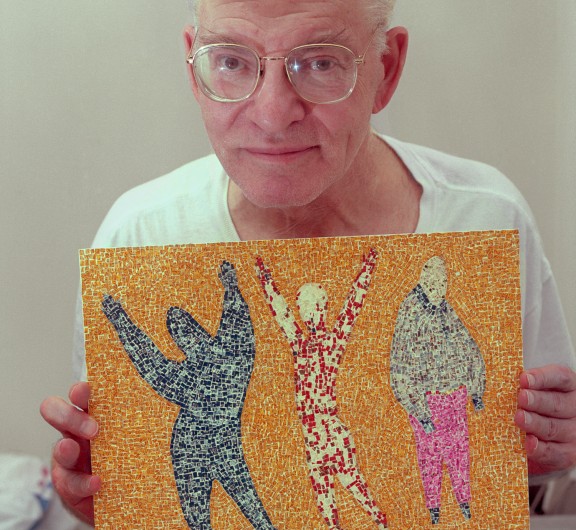

In 1973 Stella Waitzkin (1920-2003) created one of her first polyester resin books called “Autobiography.” The work, which she remade in different permutations over the next four years, featured a three-quarter scale mold of her face, cast with the help of her second son Bill. She continued the practice of sinking faces into the books, clocks, and frames that filled her lifelong project called “Details of a Lost Library” (1969-2003).

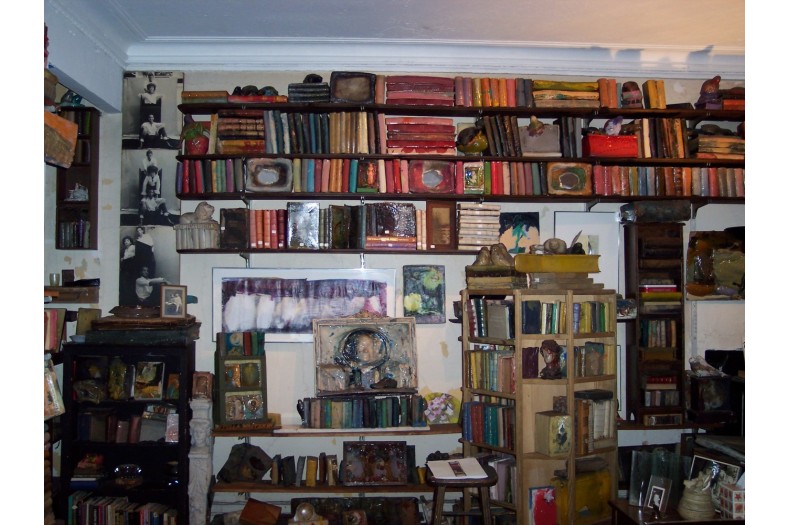

“Details of a Lost Library” was an installation of paper books, paintings, photographs, found objects, and cast resin sculptures of fruit, birds, books, and clocks. She curated the library in her Chelsea Hotel apartment. By creating an art installation that was her home, she subverted the notion of women as homemakers and decorators, claiming her position as a feminist artist.

Living in the Chelsea Hotel certainly provided endless inspiration for Waitzkin and its other residents. The Chelsea is a historic building in Greenwich Village, and it attracted avant-garde poets, musicians, performers, photographers, and all manner of artists. In fact, the artist, poet, filmmaker and “godfather” of pop art, Larry Rivers, formerly occupied Waitzkin’s apartment.

Having trained under influential abstract expressionists Hans Hoffman and Willem de Kooning, Waitzkin gathered her sensibility for an expressionistic approach to color, texture, and handling. Though she worked in three-dimensional forms, she insisted that her books were paintings and ought to be viewed as such. This approach may have developed from the rise of postmodernism, which challenged conventional categories of art and mixed styles and materials in effort to obfuscate meaning. The writings of Roland Barthes—who introduced the idea that the audience produced meaning as opposed to the maker—strongly influenced the development of postmodernism. Waitzkin echoed this philosophy in an interview about a film she had made. She said, “a painting or sculpture can’t be explained, but should be felt. Since I am an intimist and subjective and innovative, I prefer to let the film speak for itself.” In this statement, Waitzkin put the responsibility of interpreting her work on the viewer.

The New York City jazz scene also influenced her artistic approach and her works’ relationship to the audience. Waitzkin saw her creative process as immediate and intuitive—what jazz musicians might call improvisational. She was even friends with a number of jazz musicians. Between 1959 and 1962, Waitzkin lived in a basement apartment at 27 West Ninth Street, where she befriended neighbors such as the jazz writer Robert Reisner and trumpeter Tony Fruscella. It was in this apartment that she first used a kiln to melt glass to the sounds of jazz playing in the background and began to speak of her work in jazz terms. Jazz presented her with the invitation to improvise and create collages of different genres—a sort of fusing or melting process visible in Waitzkin’s blends of materials and colors in her work.

When her friend Tony Fruscella died a mere week after Waitzkin moved into the Chelsea Hotel in 1969, she held a memorial for him on WBAI, a New York City listener-supported radio station. During the segment, she contemplated the difficult life that artists faced, writing, “It is no accident that the most gifted are the ones who are most vulnerable.” As Waitzkin became increasingly interested in assemblages, she created an artwork called “Last Notes from Tony,” which included glass bottles and Fruscella’s trumpet.

Today, viewers can only imagine what it was like to enter into Waitzkin’s Chelsea Hotel installation, surrounded by the sounds of jazz and improvisation. However, her works and their melting layers of color that give way to transparency and opacity, visualize a musical moment where chords struck the tones of a New York City art scene challenging preconceived notions about art, its process, interpretation and categorization.

Kohler Foundation acquired three “walls” of Waitzkin’s Chelsea Hotel living room which were then conserved and gifted to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. These works and many more acquired later in 2016 have been installed in an intimate, jazz filled room at the JMKAC’s Art Preserve, providing an immersive experience for Waitzkin’s work. Her work is also included in many other collections, including the National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Walker Art Center, and more.

Narrative by Cortney Kramer, PhD Candidate in Art History at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

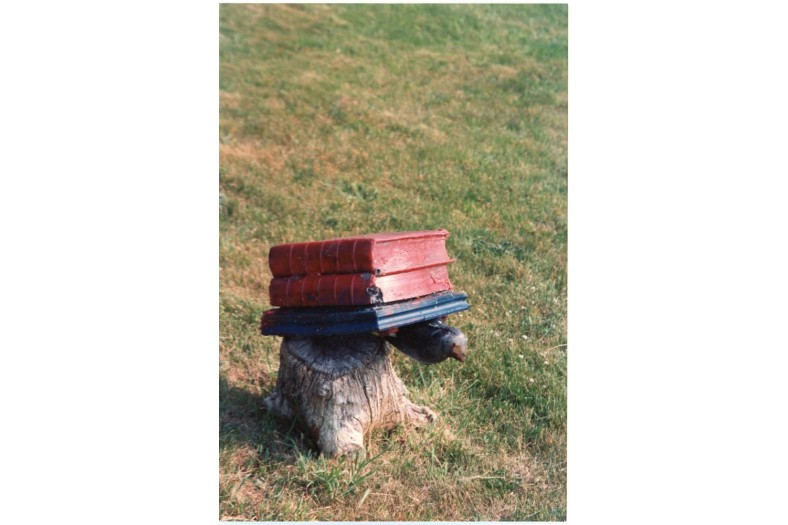

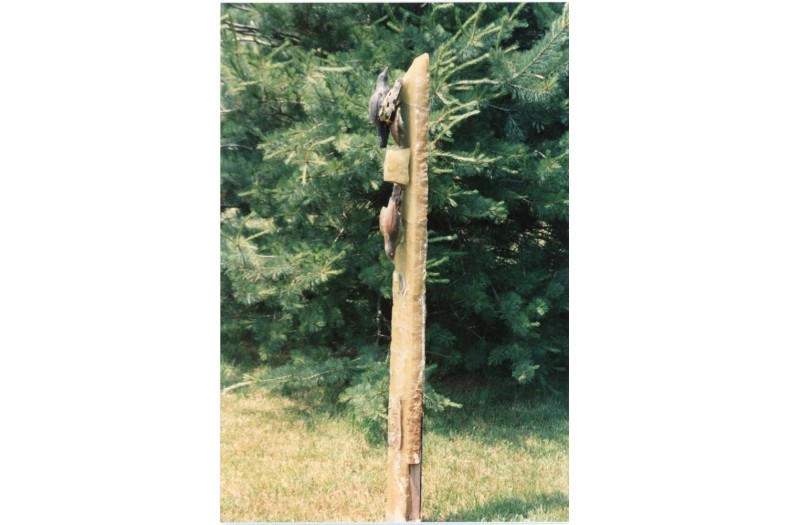

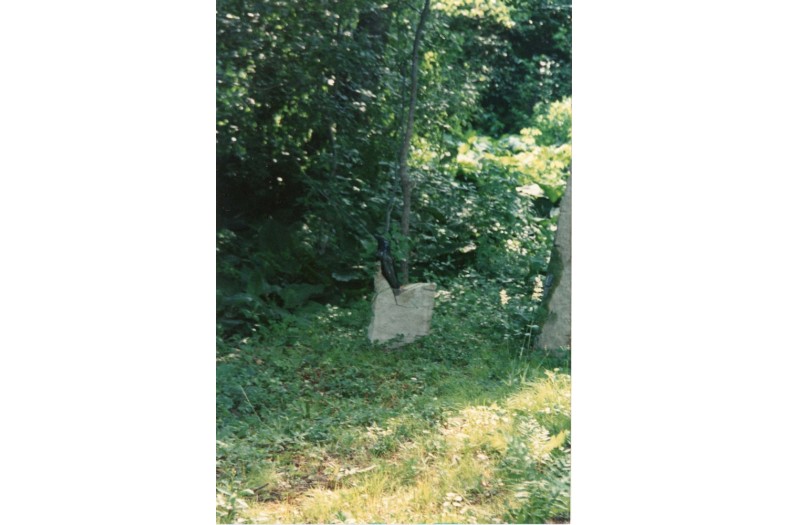

Addendum: Stella Waitzkin's creative practice extended past her time at the Chelsea Hotel to her home on Martha's Vineyard where she lived during the later part of her life. She installed work outside of her home on Music Street as well as through the surrounding landscape. These installations are pictured in photos taken by Charles Russell in 1993 (see gallery above).

Materials

resin, books, paint, photographs, found objects

SOUNDS

"Raintree County" by Stella Waitzkin's friend Tony Fruscella

Map & Site Information

222 W. 23rd St.

New York, NY, 10011

us

Latitude/Longitude: 40.7443341 / -73.9968729

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.