Yelena Dmitrievna Babanskaya and others, Various sites

About the Artist/Site

Soviet-era bus stops are now internationally recognized as architectural forms with historic, cultural and historic value, and, as the former capital of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, Almaty is particularly rich in these distinctive structures. Yet Almaty’s historic bus stops have been poorly maintained or even destroyed in the years since their construction, and until now no work has been done to systematically catalog these structures, research their history, and develop a strategy for their preservation. This is a first attempt at providing a basic history and description of the city’s historic bus stop structures.

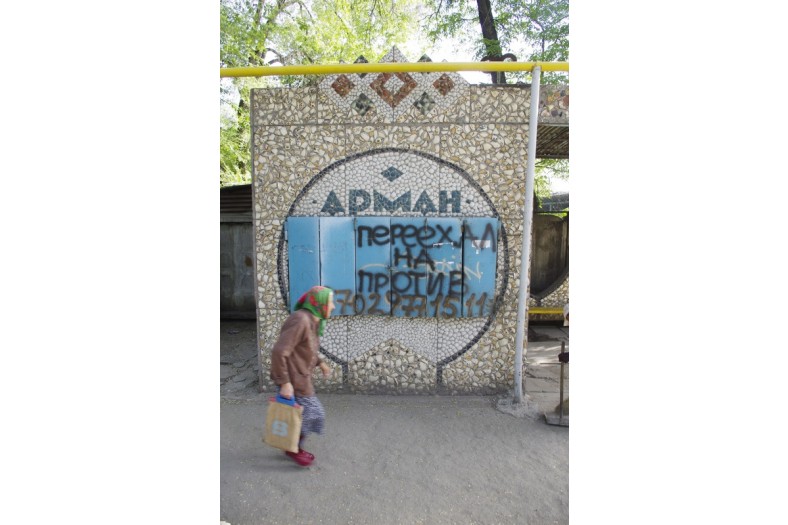

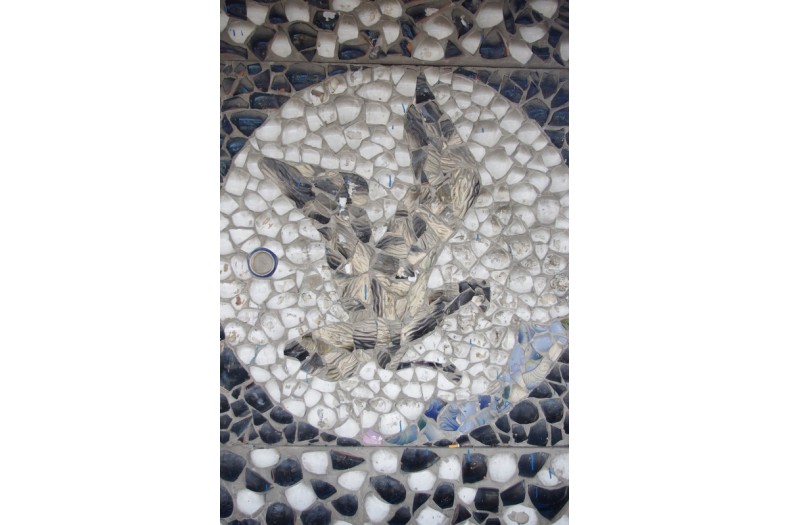

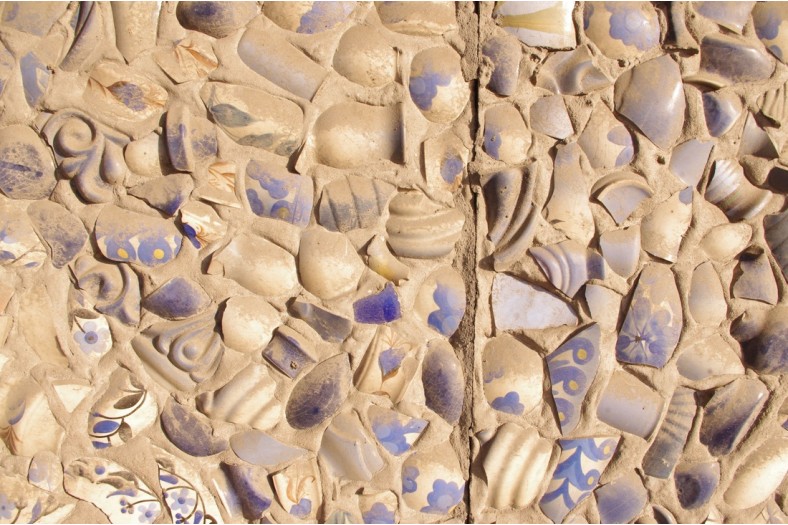

Almaty’s historic bus stops reveal three major styles. The first is the mosaic bus stop, made of concrete panels that have been decorated in mosaics made from broken porcelain dishes. (This style of mosaic is known as pique-assiette/picassiette or trencadís, and can be famously found in Antoni Gaudí’s mosaic work at the Parc Guell, Raymond Isidore’s La Maison de Picassiette in Chartres, France, Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh India; and Sabato Rodia’s Watts Towers in Watts, California, USA; while there is no conceptual connection between these artists or their works, all have been recognized by their respective governments as historic monuments.) In Almaty, broken pieces of ceramic and porcelain dishware were glued to the façades of concrete panels in images that included abstract patterns, text (“A” for Avtobus, “Arman,” or “Viktor i Ya”), and figurative images like a sun, a bird, and a galloping horse. The concrete panels were arranged into structures that complemented the striking geometry of modernist architecture. Bus stops with porcelain mosaics were located mostly on inter-city routes, and tend to be found in peripheral areas, especially in the northern parts of the city. While this style of historic bus stops are widely found in Almaty Province, there is no evidence of them elsewhere in the country.

Although these bus stops are priceless from both an architectural and artistic perspective, many of them have been destroyed, and those that survive are in poor condition. Concrete elements have decayed and need reinforcement, ceramic tesserae from the mosaics have broken off, and the façades are covered in graffiti or glue from advertisements.

The second prominent style of historic bus stop are those made of concrete panels that are faced with bas-relief sculptures. Since the bas-relief panels were made from reusable molds, identical bus stops can be found throughout Kazakhstan. Common images include those of a dombyra player, an eagle hunter, children playing on a carousel, a father with his son on his shoulders, a mother with her baby in her arms, a shepherd watching his horses, a construction worker, and one of the road workers themselves. Other elements were more abstract, such as star and diamond shapes, or referenced natural forms of flora and fauna, with images of marmots, swallows, clover leafs, and trees. While concrete panels could be mixed and matched to make every bus stop unique, there were standardized structural configurations. Bas-relief images were often painted by road workers although this painting was not part of the original designs, so the color schemes varied according to the taste of the workers and the availability of paints.

The third category of historic bus stops is less defined, and consists of those that lack any decorative elements like mosaics or bas-reliefs, but that have an interesting visual appearance because of their unusual forms. These bus stops, notably, are influenced by the design vocabulary of modernist architecture.

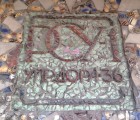

Most of Almaty’s historic bus stops were constructed at two studios in the city. Mosaic bus stops were made at a sculptural studio run by the Kazakh SSR’s Ministry of Roads’ Construction and Repair Division No. 36 (Ремонтно-строительное управление № 36 Министерства автомобильных дорог КазССР), known as RSU-36. (The name of this organization can often be found written in porcelain shards on these bus stops.) Bus stops with concrete bas-reliefs were made at the Highway Provisions Studio (цех обстановки пути) of the Almaty Stone Processing Plant, or AZOK (Алматинский завод обработки камня).

The artist Eduard Kazaryan, who worked at RSU-36’s studio, believes it was located somewhere in the lower part of the city on Ryskulov Street. In our research, we found a building at 276a Ryskulov that has a large mosaic of a road, a bridge and paving equipment, with text that identifies that building as the Kazakh SSR Ministry of Roads’ Line Operational Department of Roads No.36 (ЛЭУАД-36, Линейно-эксплуатационное Управление автомобильных дорог). It seems likely that this was the location of the original studio. The property is now rented out to several small businesses, but the mosaic remains, and the security booth is decorated in concrete blocks with porcelain mosaics.

The RSU-36 studio was the personal project of Yelena Dmitrievna Babanskaya, who managed the organization from its beginning to end. Babanskaya passed away some time in the 2010s and little is known about this influential figure. According to the recollections of her sculptor employees, one or both of her ethnically Russian parents were officers in the Tsar’s army and fled to Harbin, China sometime after the October Revolution, where there was a large Russian community. In the 1950s, the family returned to Kazakhstan.

It was Babanskaya who acquired the supply of broken porcelain that went into making Kazakhstan’s historic mosaic bus stops. The mosaics were made out of shards of broken porcelain plates, teapots and teacups. White shards came from the Kapshagai Porcelain Factory, and colored shards (mostly brown, black and blue) came from the Almaty Ceramic Factory.

The Kapchagai Porcelain Factory, located in the city of Kapchagai (Kapshagai in Kazakh) off the Almaty-Öskemen A-3 Highway at 10 Industrialnaya Street, was founded in 1975. The nearby Kapchagai Reservoir had been formed with the damming of the Ili River in the spring of 1970, and residents of the historic town of Ilisk, which was flooded by the waters, were evacuated to the new city of Novoiliisk, or New Ili, built on its western shore. The city was soon renamed Kapchagai, and many local residents worked at the factory, which produced everything from vases to china, some of which have become collectible. The factory today continues its work as Kapchagai Porcelin Inc., though with lower output.

The Almaty Ceramic Factory was founded in 1935, when it was a small workshop (гончарная) located near the banks of the Poganka River on Vinogradov Street (now Karasai Batyr Street). Specialists arrived from Belarus and the Ukraine to help develop a local ceramics industry. The factory, which employed about 500 people, had nine tunnel kilns, 15-18 meters long, that fired the ceramic pottery.

Products at both factories were tested by a quality control department (отдел технического отбора), which evaluated the pieces on a three-grade scale. Defective products that were assigned the third grade were removed and destroyed, and the broken pieces were supplied to Babanskaya’s studio, which led to the factory receiving prizes for its “wasteless production” (безотходное производство).

AZOK was located in the large industrial center north of Serikov Street, on a property that is now divided up into several small businesses that continue to work with concrete production and stone carving. The bus stops on Serikov Street nearby continue to be known by the title AZOK, and you can find the letters AZOK, made out of steel bars, crowning the bus stop on the south side of the street. At AZOK, bas-relief panels were produced from concrete. Artists carved in clay, molds were made, and concrete was poured into these molds.

Sculptors who worked at AZOK include Eduard Kazaryan, Kairzhan Tokishev, Aleksandr Tatarin, and Azat Bayarlin. They were assisted by brigades of craftsmen, known as formatory, who specialized in the making of sculptural molds.

Generally, not enough is yet known about the authors and their work to assign authorship to specific bus stops. One exception is the previously-mentioned bus stop across from AZOK itself. The design depicts road workers, with a man holding surveying equipment, a woman holding construction plans, and a road roller. According to the artist Eduard Kazaryan, there was an urgent order for a design, so Ivan Arystov, a formator who worked at AZOK with no formal artistic background, drew the sketch for the project, possibly by copying it from a magazine.

One particular bas-relief bus stop deserves mention, as it is by far the largest such bus stop in Almaty. Located on the north side of Serikov Street, also known as the AZOK stop, this site has images of a maiden and a child and a boy lounging with a dragonfly, both of which have been spotted in other locations in Kazakhstan. To the right of the main structure, however, is a continuation of six or more long horizontal bas-relief panels depicting a Soviet childhood, with children studying in school, playing volleyball, and learning the violin. These bas-reliefs seem to be unique to this structure, and they represent a particularly excellent example of Soviet monumental art in Almaty. The bus stop itself, unfortunately, is in need of repair. The roof is missing in places and concrete panels are damaged from weathering. For these reasons, the AZOK bus stop is a good first candidate for a restoration project.

It should be noted that the mosaics and bas-reliefs developed at the RSU-36 and AZOK factories would often be applied to objects besides bus stops. Panels with porcelain mosaics are found throughout Almaty, used in the façade of a bridge, the wall of a store, and even the garden pathways of a private home. A particularly valuable example of RSU-36’s mosaic art can be found at the Balbobek Kindergarten on 17 Brusilovsky in Almaty’s Tastak neighborhood, where play shelters, built in the same shape as bus stops, are decorated in impressive mosaics of fairy tale figures.

Bas-reliefs made by AZOK can also be found elsewhere, used as part of a retaining wall near the Alma-Arasan dam and decorating the sports complex of a summer camp owned by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In the Kamenka neighborhood, there is a branch of the Ministry of Roads at 1 Dauletkerei Street that still functions to this day, and its façade is decorated by a massive bas-relief sculpture of road workers. It’s very likely, given the building’s owner and the style of the bas-relief, that this work was produced at AZOK.

~Dennis Keen

Map & Site Information

Nearby Environments

Can you provide SPACES with images of this art environment?

Please get in touch!

Kitengela

Nairobi, Nairobi County

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.