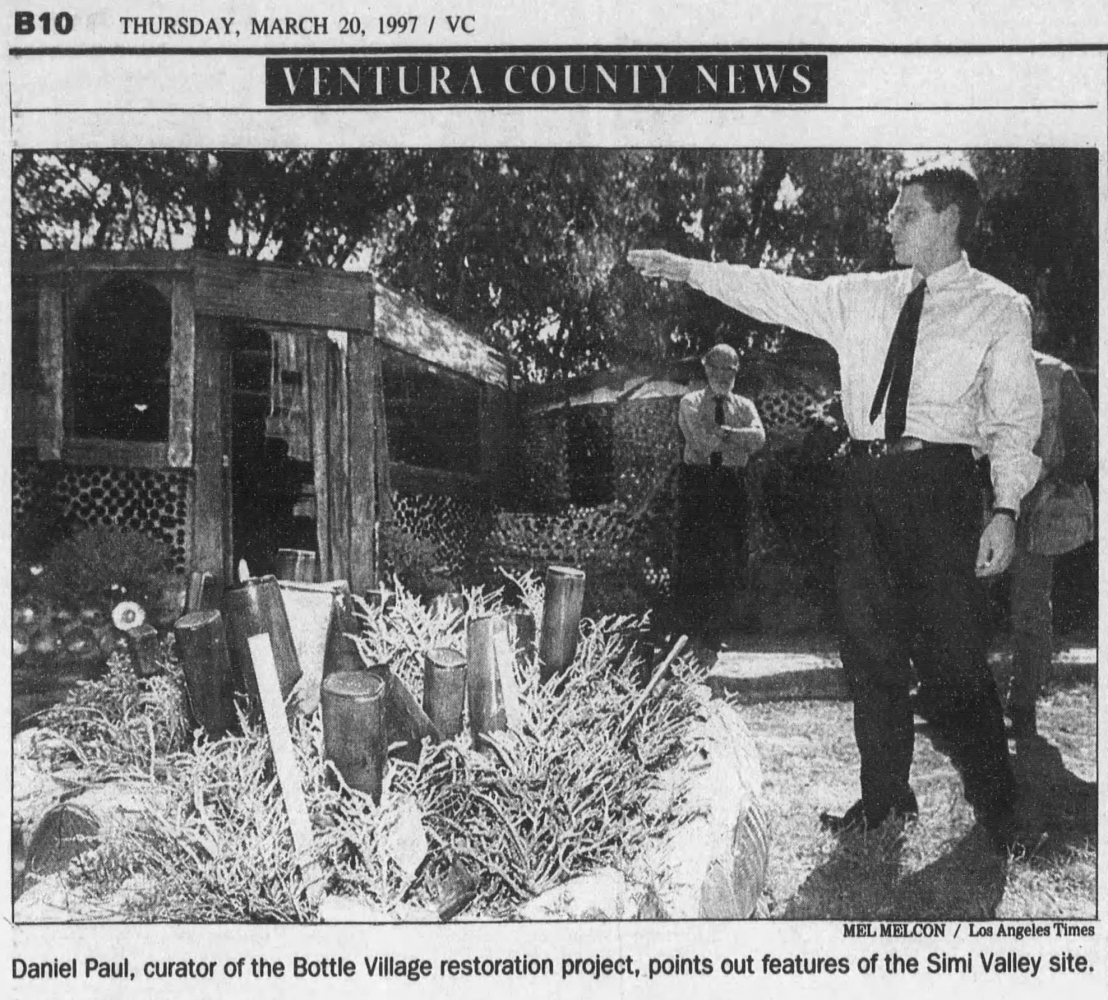

Architectural Historian Daniel Paul has more than 25 years of experience in the historic preservation field and has successfully listed local, state, and federal landmark applications that include the Capitol Records building in Hollywood, Tressa "Grandma" Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, and early U.S. Border Inspection Stations in Vermont. During his time with Bottle Village, Paul worked with SPACES Archives founder Seymour Rosen (pictured in the background of the above photo). He recently spoke with SPACES about his experiences in the field of art environments and where he sees this work headed.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your previous/ current work?

My name is Daniel Paul. From 1994 until 2010 I helped oversee Tressa “Grandma” Prisbrey's Bottle Village: an art environment located in Simi Valley, CA. Sometimes I was referred to as an Acting Director there, but either way, it was an entirely volunteer activity. I was only 21 years old when I began – so kind of on the young side! I hold a master's degree in art history (California State University, Northridge, 2004) and a short course certificate in historic preservation from a USC summer program I took in 1996. I am now a federally qualified architectural historian, which means I am able to sign certain documents and make certain calls regarding historic preservation; it is assumed with this qualification that I know my subject quite well.

After 15 years in a corporate environment, I am now in independent practice and have been since 2021. Over the years I have surveyed literally thousands of properties. I have drafted very dry technical reports that may never see the light of day, but perhaps most interesting to most, I have landmarked a variety of properties for local, State of California, and federal listing onto the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). This includes Bottle Village, back in 1996 – my first landmark application! At that time, I had no idea that what I was doing at Bottle Village was even called historic preservation.

Recent work has included getting the Integratron (A ufology site in California's Mojave desert) listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and I recently completed a draft NRHP nomination for an ecological design/art environment in Marin County, CA named The Last Resort. Other projects of mine have included landmarking the Capitol Records Building Hollywood and the entirety of Los Angeles' Griffith Park. Just last week I attended the dedication for the spot-on-reprinting of a 640' long Bicentennial Mural designed, conceived, and painted by high school kids in 1976. In a volunteer capacity, I worked in secret for eight years on that, court declarations and everything. I am considered an expert on 1970s/80s era mirror glass office park architecture – that slick, high-tech, wet-look vernacular with smooth, all over grids – a subject I have been researching for the last 22 years.

The Last Resort in Lagunitas. Photo: Jo Farb Hernandez.

How did you become introduced to/ interested in the world of art environments?

At the time I came across folk art environments, I was an undergraduate art history student extremely interested in the nexus between art and psychology. At some point, I became moved by this possibility of individuals who did not consider themselves artists in any way devoting all their lives, efforts, resources, and energies to creativity and art making. To me it seemed that there was a certain potential importance for the role of creativity in everyday life – just as humans in general, not "artists"– and I was moved by this as demonstrated through art environments. The more specific story is that I was at a museum on a Monday – forgot they are closed on Mondays! – and ended up in its bookstore in January of 1994. I saw a hardcover magazine from Japan named ArTRandom, and it was about folk art environments. Looking through its pages, I felt like I had been hit over the head in a good way, and suddenly realized that I must get involved and see the Southern California examples!

Within the next couple weeks, I called Bottle Village – one of only two Southern CA art environments featured – the other, of course, being Watts Towers. A remarkable volunteer named Janice Wilson (who at the time was overseeing Bottle Village) was insisting I could not come because, well, between the time I saw ArtRandom and the time I called a week or two later, the January 17, 1994 Northridge Earthquake happened, which damaged much of Bottle Village, so it was closed. I found a way to come anyways and immediately got involved – including meetings with Seymour Rosen right away – and basically fell in love, even with half of the art environment in shambles on the ground. Even then, what Prisbrey made over her decades was that powerful for me.

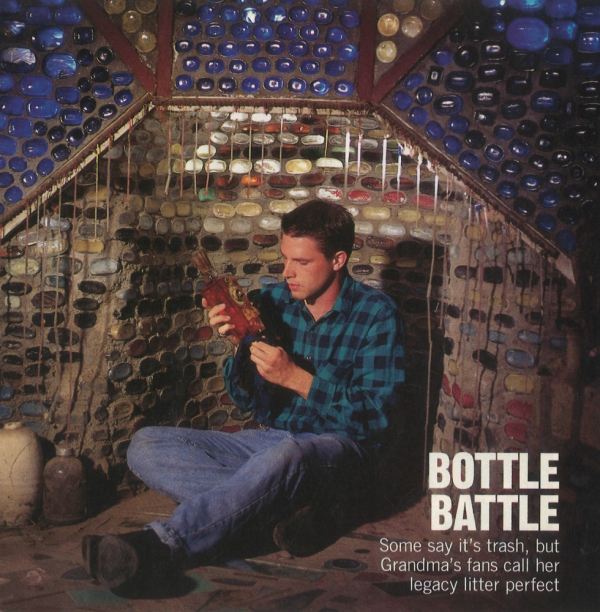

Daniel Paul pictured at Bottle Village in a June 1997 People Magazine feature titled "Bottle Battle"

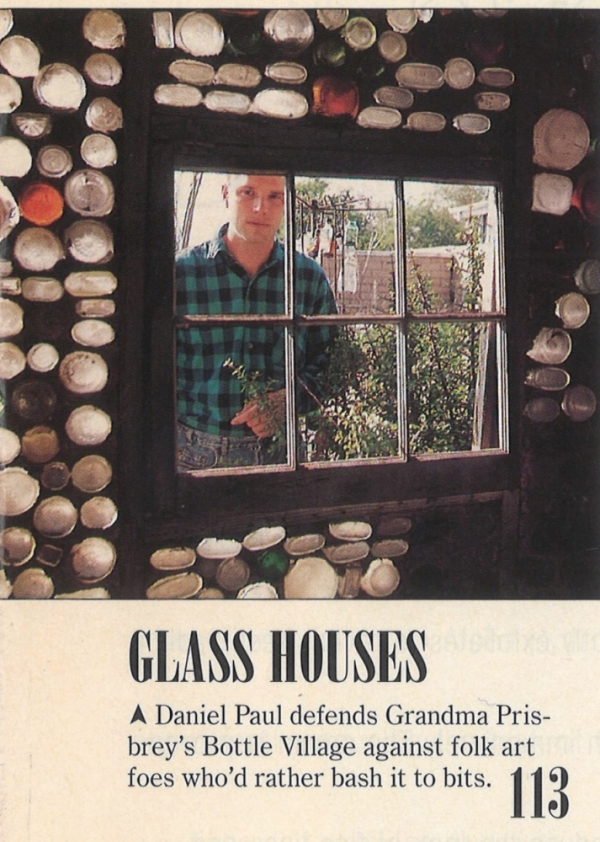

A detail from the 1997 People Magazine feature on Bottle Village.

How has this field changed since you first became involved?

Well, at the time I first got involved, it seemed like outsider art was having a moment, with magazines like Raw Vision, events like the art car parade, large publications by Phaidon, Taschen, and others. I feel that my timing was lucky in this regard. I do not feel that as many people in the general public will now relegate an art environment as crazy as they may once have, and everything, for better or worse, is now easily over exposed – for selfie purposes or otherwise. I know that Bottle Village is – if not beloved in Simi Valley – is at least left alone, when at one time some locals were perceiving the property (and Prisbrey) as embarrassments and actively trying to get rid of it.

In California, the Office of Historic Preservation (which undertakes preliminary approval of NRHP nominations, among other things) is open and savvy, but is also in some ways more circumspect. So it sometimes seems more challenging to list these properties. On the whole, I'm just thankful more people seem to know what outsider art is and younger generations seem so much more open to it, as part of a remarkable openness in general. I do worry about a certain desire for built environment homogeneity I sense among some younger people, but I hope this will not have a negative bearing on saving art environments.

Seymour Rosen, the founder of SPACES, prepared a National Register nomination for eleven art environments in 1978. All but one of the nominated sites were rejected due to the age of the site or the presence of the artist. Of the ten environments not listed, one fortunately remains in the artist’s family, two have decayed significantly, and seven have been lost entirely. The listed site, pictured above, Desert View Tower in Jacumba, Cal., is thriving

Art environments are unique sites with unique considerations. Where do you see this type of art making fitting into your work/ impacting the overarching field of historic preservation?

For the art environments I have gotten involved in preserving, one absolutely cannot wait 50 years – the typical cutoff for deeming something "historic" – before drafting that designation. The period of significance by necessity must often end fairly recently. If preservation protocols are not in place, local agencies may chomp at the bit to get rid of art environments immediately. On account of how ephemeral they are, not to mention their very materials – often never meant to be outside and therefore rapidly disappearing – art environments occupy a remarkably distinctive place in the preservation pantheon. It is not so much the need to push the preservation envelope for the sake of being clever, progressive, or different for its own sake. Instead, reviewing agencies need to make the call, sometimes right away, as to if a given art environment may have distinctive historic significance at a local, state, or federal level, for any chance to save the work. On account of property values, ambivalent heirs, or a city's litigation fears around the public at unpermitted properties, the site can literally be gone in a matter of months if not sooner, otherwise.

What do you hope to see for the field of the future?

I hope to see an understanding that if a given individual has spent decades vesting themselves in a creative process, that right there speaks for the property's historic distinction. That act, and that commitment to making an art environment, is so rare – and even rarer than before in this new, more technocratic world. In such instances there should be little doubt an art environment deserves preservation. A fast tracking of this realization would be nice to preserve any variety of threatened art environments. It's not like they are a dime a dozen. They are intrinsically distinctive, and therefore telling at some level that they can be perceived as artistically and historically significant – if not just for a local community, and the locals inspired by its presence. In this new global world, a local preservation victory can instantly become one for a much larger community of the interested. For those hungering to touch such creative expression, it becomes most rewarding to know that someday, if your travels take you there, you can experience yet another preserved art environment.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Paul.