Nothing beats the relentless march of time and elements, especially under a sun that bakes every surface in 120+ degrees days every summer. So it is no surprise that Salvation Mountain, a literal man-made mountain 28 years in the making, has been falling apart and being built back up almost daily since Leonard Knight started putting his heart into it all those years ago.

What started as a small monument made of dirt and painted cement became, over time, a sprawling adobe and hay-bale mountain complex, with peripheral structures made of telephone poles, tires, and car windows, as well as art cars and sculptures, all painted in a patchwork of stripes and color blocks of whatever paint was donated that week (estimated at over half a million gallons of latex paint!).

I remember helping Leonard carry a dozen hay bales up the mountain the first day I met him in 2007 and promised to come back again. I returned a dozen times over six years to help him build, to photograph his work, and to try to better understand his humble genius.

I watched, as he battled the elements with the thickest paint I'd ever seen and an endless plugging of cracks with fresh adobe. But eventually time and the elements take us all away too, and so when Leonard died in 2014, it was up to those who loved the mountain to continue his work.

A series of caretakers and volunteers over the years have made a valiant effort to plug the cracks and repaint the surfaces, but we have lost many parts of the mountain especially after big rains. Parts of the mountain that Leonard Built have completely collapsed and been remodeled in a close replication to Leonard’s work using old photographs, and others are just too complex to do while trying to keep up with emergency crack repair. The “Museum,” the stand-alone structure Leonard built next to the Mountain, (an architectural feat that has no influence and is without doubt my favorite part of the Mountain complex) has collapsed in a way that makes it too dangerous to enter and is too precarious to be rebuilt safely in places.

When I visit the mountain I am always so torn – grateful for all the efforts put in over the years by volunteers and caretakers, and sad that I can no longer see the hand of Leonard himself in the brushstrokes of areas that have been painted over 20 times since his passing.

As I began to learn about photogrammetry and started to build large scale cultural heritage preservation projects for National Geographic, I realized that this technique could be used to resurrect surfaces and brushstrokes long lost to time… if I could find enough images. And so I began to dig through my archives to find a day in 2009 when I had decided to photograph the entire surface of the mountain at close range. These images were flawed and filled with shadows and not made with the idea of photogrammetry in mind, but with the help of a friend and collaborator, Devlin Gandy, and funding from SPACES via Kohler Foundation, Inc., we set to work. Our goal was to stitch these images together and remove the shadows to reconstruct a 3D model of the mountain as it looked while Leonard was still alive.

We also hoped to make a way for people to be able to “walk” up the Yellow Brick road that Leonard painted winding to the summit. The Yellow Brick road has been closed for over a year now because there are not enough docents to supervise the traffic and too much surface damage to keep up with.

The results of our project accomplished all goals, and we are happy to present a model of Salvation Mountain that has its entire main surface made from those 2009 images showing Leonard’s original brushstrokes and color and includes all surrounding areas merged from 2022 drone scans:

Original 2009 stitched images at highest resolution before merging and repairs:

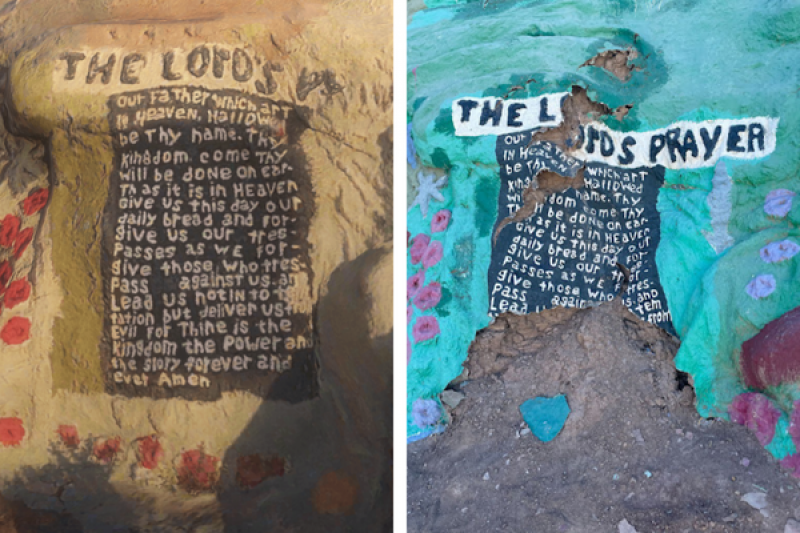

2009 Rendering of the Mountain (left) and collapsed segment in 2022 (right)

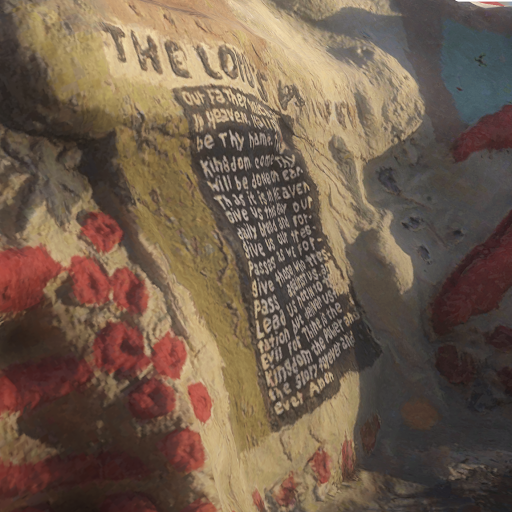

Details from the rendering featuring photos from 2009

Rendering of Salvation Mountain using photo from 2009 (left) and a photo of the same area in 2022 (right)

Other areas were not captured with enough 3D data to bring back. Seen here is the interior of the Museum.

Collapsed section rebuilt by Ron, Salvation Mountain caretaker.

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.