Almost everyone who knows art environments knows Lisa Stone. Whether through her (and for a long time, Jim Zanzi's) unparalleled class Better Homes & Gardens at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago or her steadfast commitment to the preservation and interpretation of art environments around the world, many who know Lisa have been swiftly convinced that this is the place to be. You will typically find her juggling a million projects–from curating exhibitions to hands-on conservation work, but she always makes time to generously share the vast knowledge she's collected throughout the years, including playing a large role in the creation of the original SPACES website during her tenure on the board. We're so grateful for her continued support of SPACES, and we're thrilled to share this interview with you in hopes of recognizing her extensive contributions to the field of art environments.

Stone working at the Wisconsin Concrete Park, 2007. Stone worked at the Wisconsin Concrete Park each summer, from 1988 to 2018, lead the formation of Friends of Fred Smith in 1995 and chaired the conservation committee from 1995 to 2018.

How did you get involved with SPACES?

In 1981 I met Don [Howlett] who later became my husband. A few years before that, I think it was the late 1970s, Don met Seymour. He [Don] and Sharron Quasius had done the major restoration of Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park in 1977 and ‘78. He found out about Seymour and SPACES, which had just been formed officially. First he [Don] went to Kansas and visited the Kansas environments and became good friends with some of the Kansas Grassroots Art Association folks. Around this time Seymour brought Don to California to explore many California sites. SPACES is saving and preserving arts and cultural environments, and the preservation of art environments was in its infancy. Since, other than the Watts Towers, the Wisconsin Concrete Park was the first major restoration, he [Don] was the dude! And so when I met Don, I brought him to the farm where I lived, and he showed us three slide trays of slides of art environments, so I was baptized by full immersion into the realm of art environments because of Don’s experience with Seymour and SPACES.

And then (I forget what year it was, but it was in the early '80s) Seymour, Don, and Jim Zanzi decided to have a kind of summit about art environments in Chicago. I think it might have been his idea to talk about art environments and how to get more traction with SPACES, to get the genre more widely understood. Seymour, Don, Jim [Zanzi] and Gregg Blasdel and I gathered at the Art Institute of Chicago. They gave us a room, and we had an all day meeting. I remember Seymour talking a lot about, “How do we find these environments? Do we ask postmen to report on unusual yards? How do we actively and really assertively find these sites?” And I remember Jim and Don responding, “Well, you do it by being inspired wanderers. You hone your radar. You don’t come up with a process.” Everyone had really differing ideas.

I think it was in 2000, I went to a National Trust for Historic Preservation conference in Los Angeles and Jim went also, and so we decided to have a meeting with Seymour and catch up. It was the first time I visited his home, and it was SPACES! Jo [Farb Hernández] came down from Aptos, California. By that time, Jo had been working with Seymour for years, writing grants and doing all manner of supportive work for SPACES. We met and talked about all kinds of things. I was on my path to learning as much as possible about art environments and visiting as many as possible, but I remember just sitting in this cramped little room and seeing what SPACES really was. I had imagined something much different, very organized. I thought, You’re kidding! It was such a mess. Jo deserves an enormous amount of credit for taking all of this stuff that wasn’t well-organized and kicking it into professional shape, when SPACES was reorganized after Seymour died.

After Seymour passed in 2006, SPACES was reorganized, and at the 2007 John Michael Kohler Arts Center conference, Jo asked me and Peter Tokofsky to join the board, along with Holly Metz and John Foster. We [the SPACES board] worked really hard to create parameters around how the library and the art collection and the archives would be managed. Early on, we decided we were going to put all our energies and resources into a website. Up to this point, Seymour had gathered information and images about art environments but there was no outflow, he didn’t have a way to get the information out. We decided having the mother of all websites would be the way to make SPACES effective. We put an enormous amount of work into imagining the website. John Foster was fabulous in being the liaison to the web builders, TOKY, where he worked. I remember the first thing I did–I wrote it on the airplane going home from the first board meeting–is that I really didn’t want there to be this general idea of what comprises an art environment, so I drafted a list of types of environments, actually, modes of expression, that I thought would be more helpful. That’s how I teach. I worked with an SAIC Historic Preservation student, Sarah Tietje, in creating a preservation toolbox for the website. I know it’s been helpful to a few people. I wanted it to be the go-to place for people who are desperate because a site is threatened or it’s about to be lost or it’s been common for people to “have this thing and we don’t know what to do with” and there’s nowhere to go for models and advice.

Fred Smith's Wisconsin Concrete Park in Phillips, WI. Lisa Stone.

Tell us more about Seymour and your relationship with him.

I love the fact that Seymour was really wide open about the things that he was interested in and enthusiastic about, things he was convinced were culturally important. It could be anything from drag queen parades to high school parades to any kind of ethnic or cultural celebration, art cars, just anything in the category of In Celebration of Ourselves. That’s something that I hope that SPACES KFI can more robustly collect and make visible on the website, in addition to the genre of vernacular art environments as we understand them. He also was documenting, early on, the arts scene in Los Angeles. This has become more evident and visible more recently, particularly from the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time project. There was a lot of documentation of the white but not the Black or the Latinx arts scenes in LA. I wish like hell he had documented the Brockman Gallery and other spaces that showed African American artists. But fortunately he documented exhibitions at the Ferus Gallery and that documentation in SPACES’ collection has been really important for many scholars, exhibitions, and catalogues. I appreciate the fact that he was looking not just at work by non-mainframe or non-mainstream artists, but he was looking at the larger scenes.

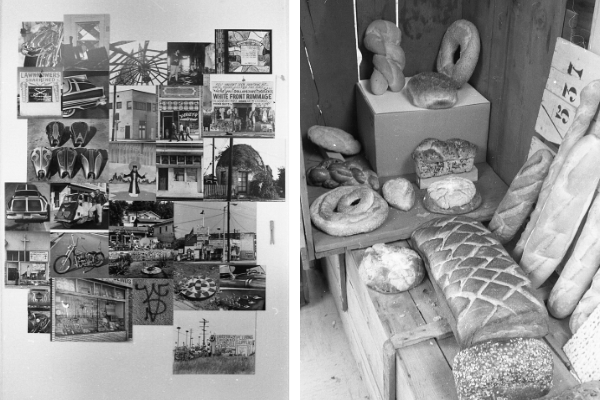

I think one of the most wonderful things he did was a show called I am Alive. I think it’s so important in terms of a curatorial approach. He took, I think a 17-mile radius* around the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and allowed people to give him stuff, collected stuff off the streets, objects that were found and representative of ordinary life, which doesn’t mean they weren’t important or valuable, in fact, it was their ordinariness that made them valuable. I think he chose the radius so it could include Watts Towers. I got a copy of the catalogue a few years ago, but I’d never seen pictures of the installation. Finally SPACES digitized and shared the installation images, and it was revelatory. It was a marvelous installation organized around huge wood crates arranged throughout the gallery, with Seymour’s photographs of Watts Towers and other places interspersed among the objects. One crate was overflowing with loaves of bread, which you could never bring into LACMA today. I Am Alive was radical at the time and needs to be exhumed at some point when you really want to talk about Seymour and Seymour as a curator. Seymour’s scope continues to excite me. (L. Stone: I’ll note here that Annalise Flynn created a thoughtful presentation on Seymour and I Am Alive, presented at the 2020 College Art Association conference.)

Installation views of I am Alive at the Los Angeles County Museum. Seymour Rosen, 1966.

What are you most proud of that SPACES has achieved over the last 50 years?

The website is the obvious achievement; it’s been the workhorse and the outward face of SPACES. But behind the scenes, the organization and digitization of massive materials can’t be underestimated. I feel like I don’t know how much of an impact SPACES has had on saving threatened sites, but we’ve tried, and I think that’s possibly a weaker link that could be improved.

What do you hope to see SPACES do in the future?

An important goal for me would be to find meaningful ways to use the resource to educate and erode the boundary between mainframe and non-mainframe even further, and of course, it’s important to me personally and certainly as an educator, that the range of expressions in the genre of art environments is absolutely in cadence with, and in many cases preceded, exigencies of the mainstream. Contemporary art critics, art historians, and arts administrators want contemporary art to satisfy a range of artistic, social, and political agendas. Most arts professionals overlook the fact that environments by self-taught artists have negotiated these arenas in complex ways for many decades. Art environments reflect and are affected by every agency of change, from fluctuations in real estate values to the impact of the climate. In addition to functioning artistically, they exist in space and time, and thus they heighten our awareness of change in the environment, beyond the environment, and of change itself. And now, in the time of COVID-19, they exemplify creative lives that take place within the context of home. Environment builders are, in so many ways, far in advance of art world trends, for these reasons as well as the increasingly examined genre of found object art. Rauschenberg didn’t invent it. Jasper Johns didn’t invent it. It’s important to say these are currents that have real relevance to each other. It would also be my goal to not keep SPACES in a non-mainframe ghetto, to include more writing, more educating, that positions art environments within other spheres.

Nick Engelbert's Grandview in Hollandale, WI. Lisa Stone, 2013.

What do you hope to see from the new SPACES/Kohler Foundation (KFI) partnership?

The transition from SPACES Aptos to SPACES KFI was a huge and challenging transfer to manage, with tender spots and moments. Jo’s been so dedicated to and consumed with and by SPACES. She lives and breathes SPACES, but it’s now transitioning to a new life. It’s in good hands. It has landed at Kohler Foundation, and the adjacency to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center and the Art Preserve is making Sheboygan exponentially more of a destination, and a place to study the genre. I always describe the western shore of Lake Michigan as an axis of inclusion–with the nodes of art museums in Sheboygan, Milwaukee, and Chicago–that doesn’t exist in the same way anywhere else.

Mary Nohl Art Environment, Fox Point, WI. Lisa Stone, 2007.

What’s next for you?

I stepped back from serving on several non-profit boards as I really need some time and space. I want to have a life beyond working all the time, which I love, but I want to go home and read. And think. I need to find out who I am and what I do–big question marks, especially in terms of future work with art environments. I want to go home and work in my garden/ruin and have a studio life (which I don’t mean as a maker of objects). And I want to figure out how to be involved with the effort to teach this material even more robustly, to encourage really hardcore enthusiastic scholarship and infiltrate, infiltrate.

Dr. Charles Smith and The African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive in Hammond, LA. Lisa Stone, January 2020.

Postscript, June 2020: Stone decided she would work one more year, and then retire from 23+ years as curator of the Roger Brown Study Collection, in August 2019. She has taught an art history course, Better Homes & Gardens: Vernacular Art Environments, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in various forms, with Jim Zanzi from 1986 to 2013, and since then, solo. She shifted the course to an online format in March, due to COVID-19; she’s teaching it online for the Ox-Bow summer camp in summer and for SAIC in fall 2020.

*Objects and photos of locations within a ten-mile-radius of LACMA were included in the exhibition I Am Alive.

Post your comment

Comments

Susanne Theis July 24, 2020

Lisa Stone is a national treasure!