Many art environments either are or start as home-based collections connected to a larger creative practice. This can make these collections somewhat elusive to archives and scholars, as they often are eventually liquidated. Fortunately, there are instances where family or friends identify that they are faced with something unique or notable. Such is the case with Irwin Rubin, who passed away after planning a museum of miniatures that never saw completion. If realized, this miniature museum could have been an art environment. Carmelle Sadfie, a student of Rubin's and founder of the Irwin Rubin Archive, has shared Rubin's story with us here that prompts us to ask — What other would-have-been art environments are out there?

Irwin Rubin, untitled leaf collage, 3.5 x 2.25 x 0.75 inches framed, c. early 1960s, photographed by Carmelle Safdie in 2019

I’m looking at a degraded digital photo of two tiny artifacts. On the right is a Byzantine-style bronze and blue-tiled cassone, standing barely one and a half inches tall. To the left is a gilt Gothic reliquary, reaching only slightly higher at its peak, its frame enclosing an upholstered cushion, atop which sits the micro-rendering of a human skull. In the photo the objects are blurry and hard to make out; at this scale the iPhone lens gives focal preference to the weave of the tablecloth below. And after Lucas Rubin, a Brooklyn-based Classics scholar and sometimes-producer of historic miniatures, texted me the photo last week, forwarding it between my flip phone and tablet in order to work on this article further obscured the image.

Lucas’s father, Irwin Rubin, a Brooklyn-born artist, collector, and educator who passed away in 2006, made these two miniature objects in the last decade of his life. They were to be, Lucas tells me, inventory for Irwin’s unrealized miniature museum, a project that would have married his interests in art, architecture, and collecting. A box of the museum components, which include diminutive representations of Victorian furniture, ancient Persian-style artifacts, and miniature Byzantine icons— as well as architectural components, for example four clock posts to be repurposed as columns for the museum’s façade— still sits in storage in the Rubin family basement.

Working with precisely-crafted details at a tiny scale wasn’t new to Irwin. In the mid 1950s, while studying under Josef Albers at the Yale School of Art, Irwin shifted his creative attention from painting to collage. He began composing works from tiny bits of paper, fabric swatches and lace, bonsai-sized leaves, razor-cut scraps of cardboard. Most of his artworks totaled just a few square inches in area. In the 1960s his output shifted to polychrome wood constructions. And while these works grew in size and projected off the wall, they often retained the minutia and intricacy of his collage work, sometimes even serving as surfaces on which to showcase tiny collages. All were framed within tight-fitting handmade wooden boxes.

Irwin Rubin, Construction #7, painted wood and collage, 8 x 3.25 x 1 inches, c. 1965-1966, photo by Chris Austin 2020

Visual complexity and intricate craftsmanship were also attributes that Irwin appreciated in the work of others, and sought out through collecting. Irwin fell in love with objet d'art from faraway places as a boy frequenting the Brooklyn Museum, guided by his mother or a grandparent reading the wall texts aloud. As soon as he was old enough to earn an income, Irwin spent a fraction of it purchasing antiques, antiquities, and artifacts from around the world. In the late 1950s, an informal mentorship with Madison Avenue dealer H. Khan Monif fueled Irwin’s interest in Islamic and Persian art in particular, but also taught him that staying ahead of buying trends ensured he could obtain museum-quality objects affordably. Other areas of interest ranged from Kachina dolls to Victoriana, as well as miniatures of all kinds. And while Irwin maintained these all-time favorite periods and styles throughout his life, he also resisted specialization. In a 2004 interview with daughter-in-law Simona Rubin he referred to himself as a tchotchke gatherer rather than a serious collector, noting that his purchasing habits were guided mostly by aesthetic impulses and affordability. For Irwin, collecting also served as an autodidactic lens for learning about the world around him through the objects he encountered in it, and he both prided and faulted himself on being a person who knew a little about a lot.

Irwin also expressed his fascination with visual complexity through the home display of his collected objects, which spilled into every corner of his domestic life. Snapshots from the 1980s show walls covered to the max, and collected furniture used as surfaces for showing off more of the collection. One display case was filled with ancient Egyptian relics, pre-Islamic bronzes, Sultanabad blue-green pottery and lusterware bowls from Rhages. A mirrored vitrine, loaded to the brim with cranberry glass, stood in front of burgundy damask wallpaper. A velvet and embroidered floral mantle cover served as the backdrop for a gilt Thai Buddha and antique clock, set off by pages of Persian calligraphy and illuminated manuscripts framed above. A Chinese cloisonné smoking set with a tray and little vases rested atop a carved wooden table, covered also with a small stone bust, inlaid boxes, a large pink and white vase. Smaller items like stick pins, antique silver tea balls, and buttons were grouped by color, size, and style. This is not to mention other prized possessions like Kwakiutl pottery, a Victorian bride’s basket, Fifth century Coptic woodcarvings, an assortment of umbrellas and canes, early Christian Roman intaglios, countless lamps and chandeliers, Victorian miniatures, a rare Plains Indian basket purchased for 98 cents in New Haven.

***

In the late 1960s, around the same time that Irwin started a family and put his studio-based practice on hold, his collecting extended to include historic architecture. Over the next three decades Irwin and his family purchased and lived in two notable homes, a landmark 1880s neo-Grec brownstone in Park Slope, and Brambleworth, an 1847 stone Gothic Revival cottage in Westchester. In 2004 Irwin noted to Simona that artifacts and furniture entering a collector’s market are almost always preserved, because conserving and caring for them is understood to be integral to their value— whereas architecture is more often, and often relentlessly, destroyed. A new homeowner may have no sensitivity to or interest in its history, might tear out hardware and moldings, even level walls, destroy entire rooms or structures. When Irwin purchased his homes he took a different approach. He didn’t just see these spaces as architecturally-splendid backdrops for showcasing his collection, which they most certainly were, but worked tirelessly to restore and customize the architecture itself, approaching the houses as an extension of the objects in his collection.

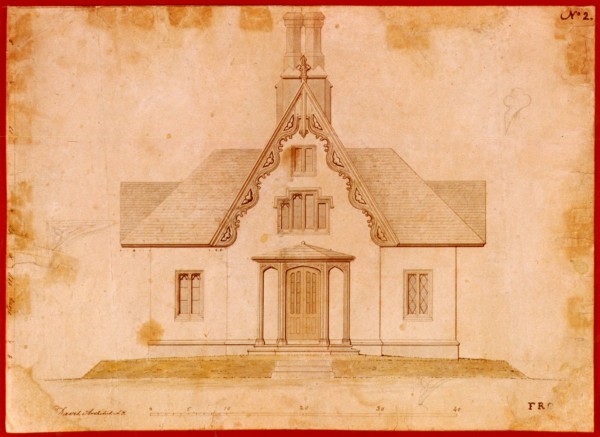

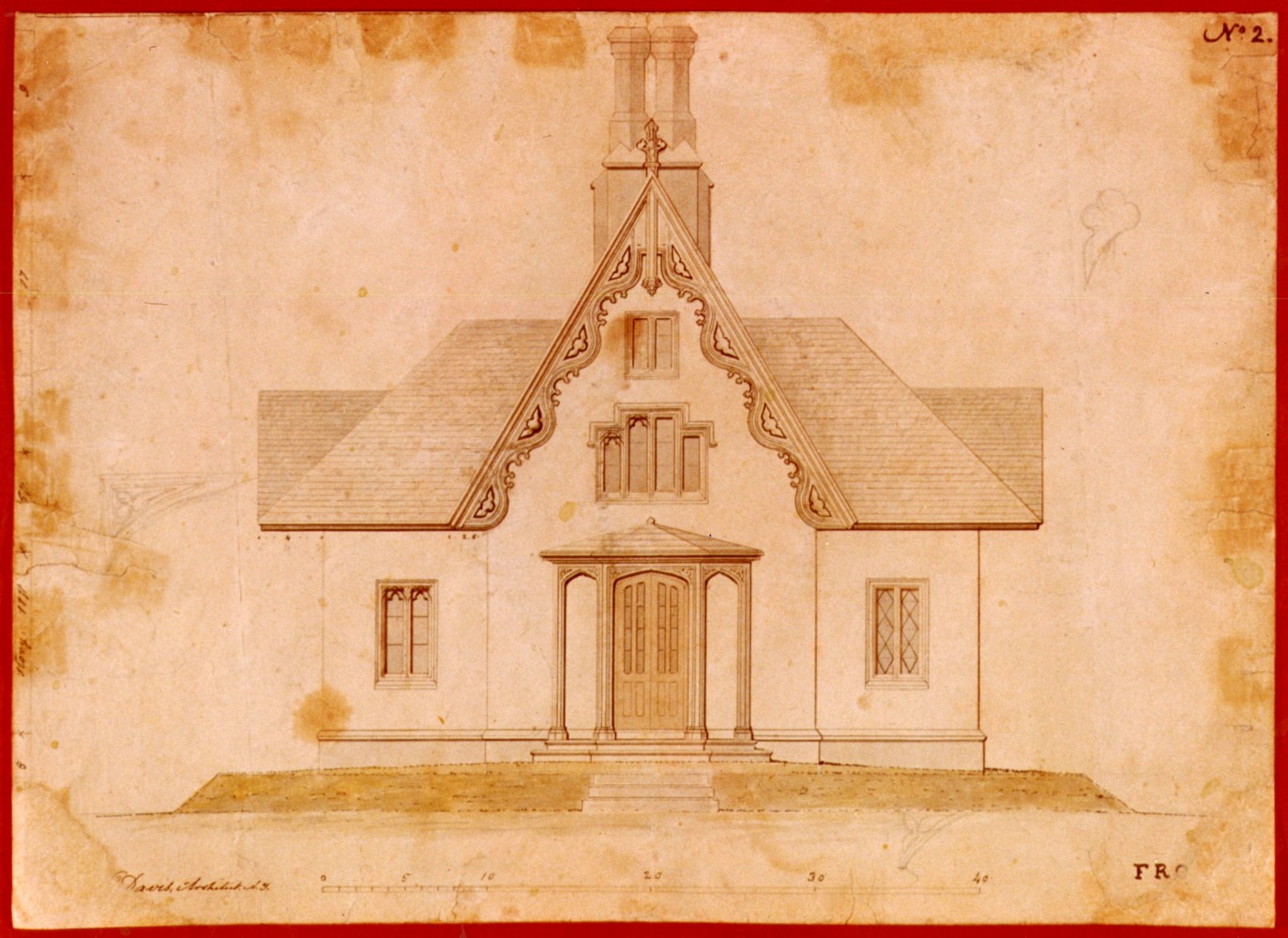

An architectural rendering of Brambleworth, designed by Alexander Jackson Davis and completed in 1847, which Irwin reproduced on a holiday card in the late 1970s or 1980s.

Brambleworth in particular, located in the Woodpile historic district of Mount Kisco, became the object of Irwin’s creative attention and obsession from the late 1970s to 90s. He poured time and resources into rebuilding parts of the house and restoring fixtures to their original glory. He reconstructed a staircase, hand-stenciled the kitchen floor, and chose antique wallpaper and accent trimmings for each room. His care also extended to the surrounding grounds, absorbed by rare plants that demanded the attention he once gave the wood constructions in his studio. In the 1960s he worked with floral themes through collage; now he cultivated unusual flowers, exploring color and composition through the dynamic and tactile practice of gardening.

A detail of the interior at Brambleworth shows collected furniture, objects and artworks set off by ornate wallpaper designs and trimmings, and historic architectural features like molding and lozenge-shaped window lattice, 35mm color photo, c. 1980s

Irwin Rubin in his garden at Brambleworth, 35mm color photo, c. 1980s

After visiting a miniature show in the 1990s, Irwin became interested in miniature display and was inspired to create custom vitrines and small rooms for showcasing the tiniest items in his collection. He built a Victorian-style room for his existing collection of antique dollhouse furniture. He played with scale by using wood scraps from his box of “findings” to stand in as wall moldings, cut up an old picture frame to make a small cove, and refashioned a landscape print into a multi-panel mural. This backdrop set the scene for an ornate carpet and tables, a love seat and dining chairs, a mirror in gold-leafed frame, a cello and inlaid guitar, and brass candelabra hanging from the ceiling. Around the same time Irwin also built a miniature Adobe room to showcase his baby Southwest-style items. This more austere diorama features tiny earthenware vessels and a Navajo rug just a few inches long. Architectural components include dark rounded wood beams spanning the ceiling, and a horizontal window inlet with wooden ledge, supported by three turned newel posts. Irwin also built a Southwest-style display case out of hand-painted cigar boxes to house his collection of miniature Southwest Indian baskets. When the baskets and case were later sold in the Brambleworth house sale, which the Rubins held when they moved back to Brooklyn in 1999, the woman who bought them remarked that it was the display case alone that compelled her to acquire the collection.

Irwin Rubin, untitled Adobe room diorama, c. 1990s, photo by Lucas Rubin 2022

By the late 1990s, Irwin’s ambitions for scale architecture expanded to include the construction of a miniature museum. This project would not only be used to showcase more of the miniature items in his collection, but would also house his own recreation of historic artifacts, like the Byzantine and Gothic-style constructions captured in Lucas’s photo. Working on a mini collection had practical space-saving appeal, but it was also a way to fill historic gaps in Irwin’s inventory by making fantasy versions of objects he encountered in books or museums but would never be able to obtain in the full-sized world. He did not draw up plans or make renderings for the museum, but told his family that he planned to fashion it after the Brooklyn Museum, the place he visited weekly as a small child and had moved back within a mile of after selling the house in Westchester. One can imagine the scope of the would-have-been project by looking at Queen Mary’s dollhouse at the V&A, where a master-crafted façade opens up to reveal stacked chambers of wondrously specific detail.

One afternoon in 1939, at the age of nine, Irwin set off to Manhattan, out running errands with his mother. At the Gimbels flagship store in Herald Square, Irwin stumbled upon a huge liquidation sale from the Hearst family collection — an entire floor of the sprawling department store was filled with artifacts from the West Coast estate. Irwin describes coming across a chastity belt, a Syrian mother-of-pearl inlaid chair, an entire church boxed up in crates, and all of it for sale. What impressed the boy was not so much the excess of relics and ornamentations; these were familiar thanks to his weekly visits to the Brooklyn Museum. What stood out was what was not there— there were no display cases, no vitrines or stanchions, no wall labels. At Gimbels, Irwin could see the stuff as stuff, dumped out in bins, spread over tables to be perused and handled, and all with price tags, cash and carry. In 2004, Irwin cited this experience as a defining moment— it was the first time he realized that he could seek out and own the objects of desire he saw from a mediated distance each week at the museum.

It’s interesting that sixty years after the fortuitous Gimbels encounter, Irwin landed on the architecture of a shrunken museum as the ideal setting for modeling his miniature world. Back at Gimbels the lack of institutional prohibitions and linear systems for categorizing culture fueled his longing to own, collect, and care for objects. It doesn’t seem unrelated that as Irwin matured as an artist he grew disenchanted with New York galleries and their dealers, and by the late 1960s withdrew from both exhibiting and making his collages and constructions. And whether it was embracing childlike ecstasy and visual excess through the vivid polychrome ornamentation in his studio-based work, or the way he ignored historical and geographical ordering in favor of a more anarchic and lived-with approach to collecting, Irwin always followed an intuitive attraction to color and crafts as a guiding principle that rejected established categories and standards of expertise.

***

I’m looking at images of the Brooklyn Museum: unrealized renderings for the massive Beaux Arts complex that McKim, Mead & White first envisioned in 1893; a washed-out black and white photo from the early 1900s taken as the masonry that stands today reached completion; a tinted postcard from the 1930s showing the façade after the grand entrance staircase had been demolished in favor of more “democratic” street-level access (this is the entrance Irwin would have known as a child); large format color slides from the 1970s and 80s with views of the museum from Eastern Parkway, more or less as we know it today minus the glass entrance that was added in 2004. The illustrations and color photographs, which depict a higher vantage point than one can obtain when approaching the building from the street, gives me a sense of what a meta version of the museum would have looked like in miniature. Seeing graphic representations of the building in its entirety, the Eclectic Roman-style features appear cake-like. The saucer dome atop the central pavilion becomes a dominant formal element, flanked by the Neoclassical columns, gridded projections around the windows, and a row of twenty-eight sculpted allegorical figures sit on blocks, checkered by their shadows cast along the attic story.

Photographer unknown, "Brooklyn Museum: exterior. View of the Eastern Parkway façade from the northeast, showing Eastern Parkway and Washington Avenue in the foreground, 1987." 4 x 5 inch color negative, 1987, Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives: Photograph Collection

Irwin Rubin’s untitled sculpture, painted wood and collage, 7.25 x 5 x 3.75 inches, c. 1965, photo by Chris Austin 2020

These images of the museum make me think of a small orange and yellow sculpture that Irwin made in 1965. It is one of only two known freestanding objects that he produced in his studio, and stands just seven inches tall when measured to include its tabletop pedestal. It’s made from what look like salvaged scraps of dowels and wooden knobs, maybe even repurposed beads or board game pieces. Delicate posts, not much thicker than a wooden kebab skewer, are adorned with teeny collaged florets at their base. When I first encountered this citrus-colored sculpture, I associated it with the more fabulous examples of Eastern Orthodox architecture, like Saint Basil's Cathedral in Moscow’s Red Square. I saw it as an extension of Irwin’s fascination with the art of bygone eras and distant lands, formed during childhood through those early visits to the museum. But reconsidering it now, in relation to the Brooklyn Museum façade and its potential for miniaturization by Irwin, I see the untitled sculpture as an expression of the world immediately around him. And I see the unbuilt miniature museum, with its clock post columns— maybe a repurposed salad bowl would serve as the dome?— imbued with the same joy I take from his artworks, and the delight that comes with diligently and meticulously shrinking the world into miniature.

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.