SPACES Director Jo Farb Hernández, Luisa Del Giudice, Jeanne Morgan, Rosie Lee Hooks – Watts Towers Art Center. Photo by Paul Harris, courtesy Luisa Del Giudice

Born on September 20, 1926, Jeanne Smith Morgan was primarily raised by her grandmother, a Nebraska pioneer and one-room schoolteacher who was born in a sod house on the prairie. She learned early about perseverance, hard work, and to focus on what was important; she never used a mirror (it was hung too high for her to see into it as a child), nor a flush toilet or an electric light until she went to first grade. But she learned how to read and write from her grandfather, a house carpenter and farmer whose mother was a full-blooded Kentucky Cherokee, and how to make willow whistles, wren houses, and much more. Her grandparents were born only two decades after the end of the Civil War, so the Northern anti-slavery culture and its songs filled their home; she was taught about equality and equity and grew up to be a strong leftist thinker, sympathetic to those less fortunate than herself. But she also, from the very beginning, had an “eye,” and, after having received accolades for a picture of The Night that she drew with her Christmas Crayolas, her grandmother believed that she was born to be an artist.

In 1940, when Morgan was in 8th grade, her grandmother died, and she moved to Denver with her mother and stepfather. Based on her art work, at age 14 she won a summer art scholarship to Denver University, an award that was granted to her in subsequent years as well. Thanks to her “dysfunctional family,” however, she became a ward of the court two years later; to overcompensate, she became VP of her class, All-School Show Producer, and more. She won a scholarship to Colorado College, but after one semester, with hopes for better art teachers, she scraped together $70 for train fare to New York to “study in the museums and find the socialists.” She married soon after her arrival, and she and her husband became “anti-Stalin social revolutionaries.”

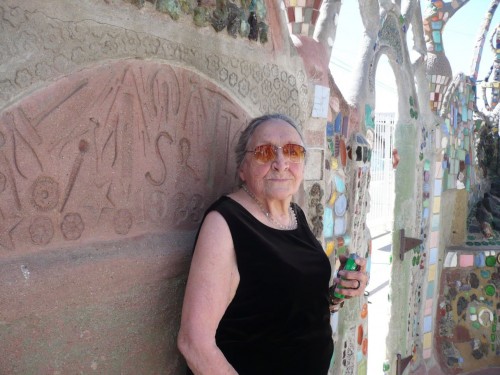

Jeanne Morgan, photo by Jo Farb Hernández.

Morgan moved to Los Angeles in 1948, where she continued to be involved in the art scene on many levels, including painting a large public mural of Emiliano Zapata. Soon she received yet another scholarship, this one to attend the Otis Art Institute to obtain her MFA. Several years later, as a young art student and “trusted socialist,” she was invited to a civil rights meeting in South Central Los Angeles – Watts. The civil rights revolution was boiling, and with her friends traveling to the South to register voters, Morgan had been feeling like a renegade nonparticipant, focused on art school instead of being on the front lines of major social change. She never made it to that meeting, however, because she became lost and hit the eastern dead end of 107th street. Suddenly, she forgot all about the meeting, as she was confronted with one of the most spectacular and monumental works of art ever created by a single human: the Towers of Sabato Rodia.

Even awash in trash, the Towers indeed changed Morgan’s life. She vowed to do everything she could to salvage and bring further visibility to this marvelous achievement by this then-unknown artist. She brought other students to Watts with her, organizing Art Students for Watts Towers; even knowing they shouldn’t, they all climbed the Towers anyway, unable to resist. Toward the end of 1958, she learned from her artist friend Mae Babitz that there was a group of older Los Angeles professionals – architects, actors, designers, artists, and teachers who also wanted to support the Towers – and together, at that first December meeting at Hollyhock House, they founded the Committee for the Preservation of Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts (CSRTW), the original name of the group that would eventually be incorporated as a nonprofit corporation. Film editor Bill Cartwright and actor Nick King, who had just purchased the Towers from Rodia’s neighbor for $3000, urged the new Committee to work to defeat the City’s recently discovered Demolition Order, an order the neighbor had neglected to disclose when he happily sold them the property. The Committee’s success in doing so – after a gut-wrenching “stress test” in October, 1959 designed by aeronautical engineer Bud Goldstone – was the first step toward preservation, and, indeed, to ultimate worldwide recognition for this spectacular site.

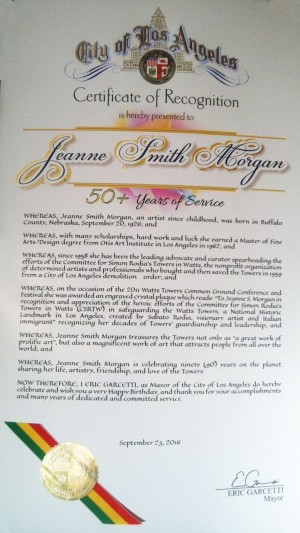

City of Los Angeles Proclamation

But those early years weren’t easy – indeed, none of them were. Morgan describes herself as a “foot soldier” for the CSRTW, drawing up petitions and learning to stand up to the macho anti-cultural city authorities who only saw a pile of junk where she saw a masterpiece. In 1961 she and Mae Babitz traveled to Northern California to meet Rodia, carrying small gifts and telling him of their awe about what he had created. “We intended to amaze and cheer him,” she writes, “and we did.” This was the first of many trips for Morgan, and other CSRTW members followed; during one of those visits, it was arranged for Rodia to speak to students at the nearby Berkeley campus of the University of California in conjunction with a showing of the 1953 William Hale film; there, documented by SPACES founder Seymour Rosen, the artist received a standing ovation.

In 1962 Morgan finished her MFA at Otis, with her thesis concentrating on contemporary methods in stained glass, a project inspired by the Towers and one that, ultimately, provided her with the chemical and technical knowledge to demonstrate varied rates of molecular movement in heat, the exact problem suffered by the Towers. Because Rodia had used a variety of materials with distinct and incompatible molecular structures, they compressed each other as they each uniquely reacted to the sun and heat; this differential movement created cracks that allowed moisture to seep into the metal cores and rust the armatures, thus endangering the structures’ stability. Morgan, therefore, knew on a much more technical level what was necessary for their durability over the long term, knowledge some of the people entrusted with preserving the Towers did not share.

As civil rights actions were heating up, members of the CSRTW knew that they could not, in good conscience, ignore the community in which the Towers were located. It had earlier been a diverse and multicultural neighborhood, but by the early 1960s it had become primarily African-American, as the earlier Japanese and Mexican residents had moved on. It was clear to Morgan that the broader philosophical, political, and sociological impact of the sculptures was as profound as their aesthetic power: “The relation of art and success arose. We couldn’t believe that a work of such great value and noble achievement could be so lost, so unknown. It was a shocking testimony to the plight of Watts’ people, who were certainly as ignored as were Rodia’s mighty sculptures. The Towers were like a jewel in a wound.”

So, in 1965, now as Executive Director of the CSRTW, she was sent by her Board to staff an office in a little white house near the Towers that had been purchased two years earlier in order to provide a safe space in which they could offer free art classes to local children. Lucille Krasne, the children’s art instructor at the Pasadena Museum, had volunteered to teach classes near the Towers beginning in 1961, and once the office was established the untrained children ran in and out while their parents, thinking that this was a new social service agency, came in with pleas to help release a son from jail or provide food for a daughter’s baby. Yet while peace was mostly made with members of the community, Morgan recalls a self-styled “Mao Revolutionary” wearing khaki fatigues and a cap emblazoned with a large red star, wearing dark pancake makeup so as to blend in better with the local community, who yelled at her with great hostility: “You gettcher white ass out of here!” Of course, she didn’t.

City of Los Angeles Proclamation

The trust and appreciation of the community has waxed and waned over the years for those mostly white pioneers who, driven by their marvel at Rodia’s constructions, also became involved in trying to improve lives in Watts. After the Watts rebellion in 1965 – from which the Towers emerged unscathed – the neighborhood was no longer seen as safe for white visitors, and the Committee’s only income, derived from tours of the Towers, dried up. Nevertheless, the CSRTW continued working, and through volunteer labor and fundraising – including the “One Square Inch” campaign that sold miniscule portions of the Towers to supporters – succeeded in expanding those art classes, the earliest ones taught outdoors, into a permanent and handsome space, the Watts Towers Art Center. Inaugurated in 1970, it has become one of L.A.’s most dynamic cultural centers, with an ongoing series of exhibitions, performances, and festivals that draw thousands of visitors each year.

By 1975, however, the Committee had no further funds, and some members were aging and/or moving away. Because the City of Los Angeles promised a complete restoration, touting Rodia’s work as a monumental aesthetic achievement, the decision was made to gift them the property. Relieved and reassured, the CSRTW signed a contract that included a clause requiring the City to solicit and receive the Committee’s approval for any matters impacting the Towers. However, the City ignored the contract, and, shortly thereafter, formally sold the Towers to the State of California for $207,000, with a lease-back to operate the Towers for fifty years. The City then transferred management of the Towers from the Department of Cultural Affairs to the Department of Public Works, more commonly in charge of LA’s sewers and streets than of works of art. DPW Director Warren Hollier then contracted with his friend Ralph Vaughn to manage the restoration process. An unlicensed and unscrupulous contractor who hired local youth and directed them to pry off anything that was loose on the Towers, Vaughn’s intent was to reinstall the “rubble” later according to his own designs, rather than those of Rodia. “It’s folk art,” he cried, “and we’re folks! Better than Rodia!”

Thanks to pro bono legal help from Carlyle Hall’s Center for Laws in the Public Interest, the CSRTW sued the City, and in 1979 ultimately won case C259603 in Superior Court, cancelling Vaughn’s contract. Further, a complementary Los Angeles Times investigation exposed kickbacks to the head of the DPW, forcing his resignation. Other local officials, including the mayor’s daughter, were also implicated in the illicit purchase of supplies and other materials. But despite this hard-won victory, ill-informed and unethical attempts to conserve the Towers continued in subsequent years; as late as 2006, Morgan and others helped prevent another City-sponsored crew from shoddy and inexpert repair. But they were too late to stop a crew member who destroyed Rodia’s signature – his right handprint placed in the wet mortar just west of the exterior north wall gate. A poor reproduction has now replaced it.

Rosie Lee Hooks, Jeanne Morgan, and Jack Jones III from the City of Los Angeles, photo by Jo Farb Hernández

Morgan has worked for almost sixty years with the Towers as Executive Director and/or Curator of the CSRTW, and the more involved she became, the more complex and challenging the work became. Nevertheless, she concurrently prolifically continued to produce her own art, and explore the work of those other artists whose works she finds of particular interest. Also a compelling writer, she served as Managing Editor of the Los Angeles Free Press, and both her creative work and her writings analyzing the Towers have appeared in national and international publications. Her most recent publication is An Interpretation of Goya's Caprichos: With 80 Interpretive Line Drawings.

Morgan, at 90, now rarely visits the Towers, partly due to her move, around 1981, to Santa Barbara, some two hours north. Nevertheless, she continues to draw them, and to brainstorm and write about them, as she sends out regular missives advocating for their safety and preservation – an increasingly lonely job, as most of her original CSRTW compatriots have passed on or have grown tired of the fight. She is relieved and delighted that now, with trained conservators from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art having undertaking the task of conservation, basing their design on the meticulous vintage photographs taken of the Towersand their hands-on work on real science, new technology may help to better preserve Rodia’s masterpiece for the long term.

Interested parties and stakeholders in the bid to have the Watts Towers honored as a cultural heritage site through UNESCO. Photo courtesy Luisa Del Giudice

On September 25, Morgan’s 90th birthday was celebrated at the Towers. Joined by new and old friends – including some she had never met in person but with whom she had corresponded over the decades – SPACES hosted a luncheon to celebrate the proclamations of service and gratitude granted her by the City of Los Angeles, her longtime opponent. Rosie Lee Hooks, Director of the Watts Towers Art Center, and Luisa Del Giudice, prime mover behind the Watts Common Ground Initiative and the initiative to place the Towers on UNESCO’s list for consideration for cultural heritage status, joined SPACES Director Jo Farb Hernández and others in feting Morgan’s achievements. Her long and productive life, working in a variety of ways on a variety of levels, has been spent trying to expand artistic horizons and appreciation for artworks often unknown or underappreciated, and to right often egregious wrongs that others often shrank from challenging. She is an inspiration to all of us to continue this struggle.

- Jo Farb Hernández, based on personal emails from Morgan to author, July through September, 2016. Excerpts from this text will be published in the December 2016 issue of Folk Art Messenger.

Post your comment

Comments

Jill Casty August 4, 2022

I have been looking for Jeanne . . . We are old friends but I haven't spoken with her for several years. I see she turned 90 six years ago. Is she still with us? If so, I would love to be in touch. jillcasty@jillcastyglassart.com I am in Seaside, CA, on the Monterey Peninsula. 831-224-3798 I do hope someone will let me know. Thanks.