Intrigued by the nature of artist-built environments, how they are conceived, what they become, their impact and connection with the public and the community in which they are created, it was more than a dream come true to embark on a field research trip to Detroit to visit The Heidelberg Project, C.A.N. Art Handworks, Detroit Industrial Gallery, and the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum.

I chose Detroit because as an admirer of innovative placemaking, I was eager to experience several extraordinary art environments in Detroit created by visionary artists working with recycled and found materials. I decided to visit The Heidelberg Project by Tyree Guyton for its transformation of his neighborhood into a colorful, symbolic landscape celebrating community; C.A.N. Art Handworks by Carlos Nielbock for his creativity in turning everyday cast-offs into vibrant sculptures and his connection to West African roots; Detroit Industrial Gallery by Timothy Burke for his documentation of the city's working-class stories through industrial remnants; and Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum by Olayami Dabls for his innovative assemblage methods and Afrofuturist themes. My main goal was to explore current preservation practices and investigate the balance between preservation and usage of these artist-built environments, aiming to develop an understanding of effective techniques, materials, and approaches for preserving the artistic integrity and authenticity of such sites.

These environments, ranging from sprawling outdoor installations to repurposed industrial spaces, represent more than just art – they're living, breathing testaments to Detroit's creative spirit. But a recent exploration as a young preservationist with a keen interest and a desire to know more reveals that maintaining these spaces while allowing them to fulfill their intended purpose is a delicate balancing act.

Photo credit: Andy Sturm

Take the iconic Heidelberg Project, for instance. Created by Tyree Guyton, this outdoor art installation spans several city blocks in a neighborhood that has suffered from years of disinvestment and economic decline. Guyton's work transforms this urban blight—characterized by abandoned homes, vacant lots, and crumbling infrastructure—into a colorful, symbolic landscape. His art serves as a vibrant response to the area's challenges, turning neglected spaces into a thought-provoking community asset. Guyton's perspective on preservation is enlightening: "It's not so much about the work but what it has created, which is a sacred space, and the story that needs to be told." This philosophy in a way challenges traditional notions of preservation, suggesting that the essence of the artwork lies not only in its physical components, but also in the community and the dialogue it creates.

William with Mr. Guyton making a polka dot in the Heidelberg street. Photo credit: Andy Sturm

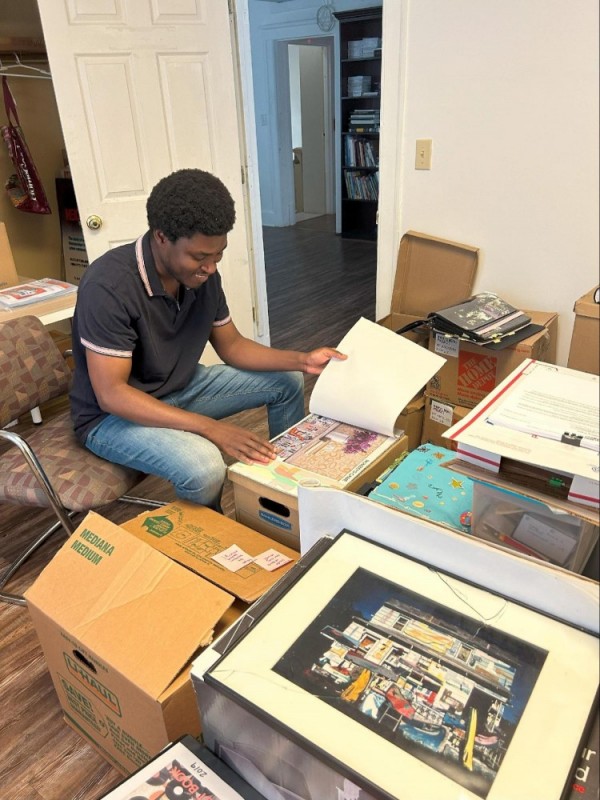

Going through the Heidelberg Project Archive. Photo credit: Andy Sturm

Caption: William making a polka dot in the Heidelberg Street. Photo credit: Andy Sturm

Photo credit: William Richardson

Similarly, at the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum, artist Olayami Dabls views his massive, immersive art environment as an ever-changing installation. Made from found objects and recycled materials, Dabls is less concerned with the physical preservation of individual pieces and more focused on the ongoing transformation of the space. This approach aligns with the temporary nature of his art, emphasizing concept over permanence.

William at DABLS MBAD Museum Photo credit: Andy Sturm

Photo credit: William Richardson

Contrast this with Timothy Burke's Detroit Industrial Gallery, which takes a more traditional approach to preservation. Burke's work, which documents Detroit's industrial past, could potentially be preserved through routine maintenance and possibly housed in a museum setting. This highlights the diverse preservation needs within the spectrum of artist-built environments.

Photo credit: Tim Burke

Gift from Tim Burke. Photo credit: William Richardson

The preservation challenges facing these spaces are numerous. Limited resources, lack of institutional support, and Detroit's specific issues of disinvestment and socioeconomic disparities all play a role. Yet, the artists behind these environments remain committed to their vision of transforming Detroit through art.

At C.A.N. Art Handworks by Carlos Nielbock. Photo credit: Andy Sturm.

At C.A.N. Art Handworks with Carlos Nielbock. Photo credit: Andy Sturm

So, how do we strike a balance between preservation and utilization? The artists themselves offer some insights:

- Focus on legacy and narrative: Preserve the story and impact of the artwork, not just its physical components.

- Encourage continued artistic engagement: Allow spaces to evolve and remain relevant to their communities.

- Provide educational opportunities: Create curricula based on these projects and engage students in hands-on learning experiences.

- Offer administrative and financial support: Help artists manage their spaces and secure sustainable funding.

- Recognize expertise: Compensate artists for lectures and site visits, acknowledging their unique skills and knowledge.

The key seems to lie in a flexible approach to preservation – one that honors the original intent of these environments while allowing them to grow and adapt. This might mean documenting the history and significance of these spaces through photographs, interviews, and academic studies, while still permitting the physical spaces to change over time.

Also, finding innovative ways to preserve the legacy of these spaces while allowing for their continued evolution can help maintain their actual value as hubs for community-driven and socially engaged art.

In the end, preserving Detroit's artist-built environments is about more than maintaining physical structures. It's about preserving a spirit of creativity, community engagement, and urban transformation. As these spaces continue to evolve, they challenge us to rethink our approach to preservation, pushing us to consider not just the art itself, but the living, breathing ecosystems these environments create.

The future of Detroit's artist-built environments remains bright. But one thing is clear: their preservation will require as much creativity and innovation as the artworks themselves. In this delicate dance between preservation and utilization, Detroit has the opportunity to contribute to a new approach – one that keeps the spirit of these unique spaces alive for generations to come.

Acknowledgements

This field research trip was facilitated by the Roads Scholarship for Research and Travel, an anonymously endowed scholarship opportunity for students who complete the Better Homes & Gardens course at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago taught by Professor Annalise Flynn, an expert in the field for whom I am very grateful. I'm deeply grateful to Mr. Andrew Strum, Executive Director of The Heidelberg Project, who facilitated my visit to Detroit and arranged meetings with the artists. My sincere thanks go to all the artists: Mr. Tyree Guyton, Mr. Carlos Nielbock, Mr. Timothy Burke, and Mr. Olayami Dabls for their warm reception and insightful discussions about their work. Finally, I extend my appreciation to Professor Nicholas Lowe, Chair of the Historic Preservation Department at SAIC, and ultimately to the anonymous donor who financed this trip.

Post your comment

Comments

Randy November 20, 2024

Your intriguing journey is amazing to read about. Wishing you all the best in your continued success!