Being in an artist-built environment is all-consuming; however, if you have never been to one before, it can be hard to conceptualize just how immersive the experience feels. Due to the fact that they are often built in the home and/or yard of the artist and are the product of decades-long (and sometimes a lifetime of) construction, the sites overwhelm. For my dissertation research, it has been imperative to visit and experience the extant sites of my dissertation: Mary Nohl’s Art Environment, Dr. Charles Smith’s “African American Heritage Museum and Black Veteran’s Archive,” and Sam Rodia’s “Watts Towers.”

While I was writing my first chapter, I had the special privilege of residing and researching in the Mary Nohl Art Environment for two weeks. My extended stay at the Mary Nohl House catalyzed numerous insights, but perhaps the most profound came from the juxtaposition of the archival boxes that I was sifting through each day with the immediacy of the site: I was viewing 2D materials chronicling history alongside the 3D art environment chronicling the moment. Being able to cross-examine the archive with my surroundings heightened my awareness of the sculptures that were no longer right in front of me. In the writing that follows, I will share some of my favorite sculptures from what I deem her “Impermanent Collection.”

Since Nohl’s site has very limited public access, managed by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC), Milwaukeeans mostly experience her site by peering through the fence. So, if you were to visit her site it would most likely be framed by your attempt to align your eye (or camera) with the fence to get an unobstructed view:

Photo by author, 2023

Her concrete Easter Island busts, fish friend sculptures, and eight-foot dinosaur are some of the most visible from this vantage, and thus have become staples of the site. If you were to venture to her site today, you could see them all smiling back at you. Despite the abundance of sculptures that are preserved on site currently, there are many more sculptures that have historically adorned her site that are now lost to time or housed at the JMKAC Art Preserve.

Water Mobiles

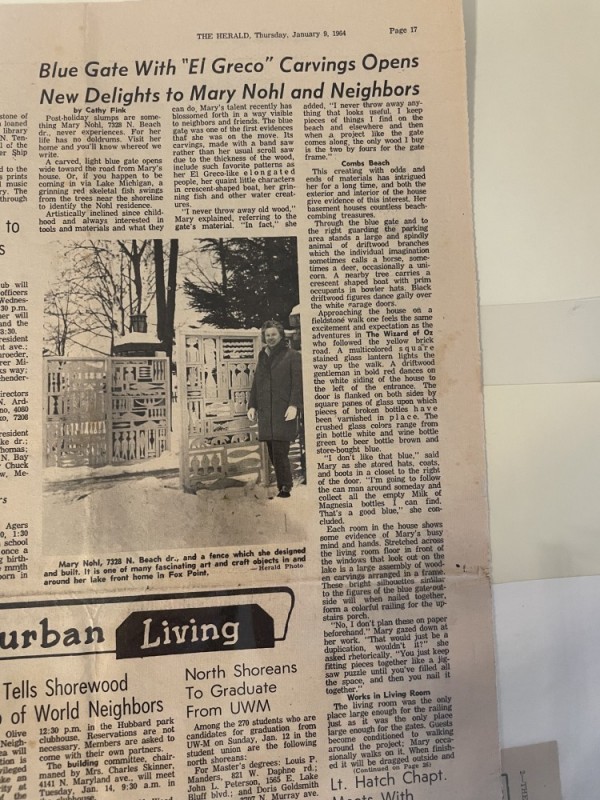

While I was paging through an archival box full of newspaper articles written on Mary Nohl, I encountered her water mobiles. They were introduced to me in “Blue Gate with ‘El Greco’ Carvings Opens New Delights to Mary Nohl and Neighbors” published by The Herald in 1964. In the article, Mary walks the journalist, Cathy Fink, around the site and provides anecdotes and extra texture for all they are observing.

Photo by author, 2023

In one anecdote, while explaining her first modification to the house, the hanging red fish, they discuss the inevitable decay of her sculptures out in the elements and the unfortunate and complete demise of one:

“For all of its ten to twelve years of tree swinging, the fish has held up remarkably well. This, Mary revealed, is because she has a spare fish in the garage in case winds damage and drop this one. At one time she had a boat load of bowler-hatted people floating in the lake.

‘This was great until strong waves would wash them down to Whitefish Bay, and I’d have to go down and shag them.’

One of the newest ideas on her big list is extending a cable from a rock out in the lake to the shoreline and attaching water mobiles: a boat, a fish or whale to the cable and letting it play in the waves” (25).

After reading that charming story, every time I walked the shore and gazed out over the lake, I could not help but imagine bowler-hat boaters anchored out there and riding the waves. Given her diary entries, my sense is that these water mobiles presented logistical challenges over the years; in 1968, she wrote that “one of my model boats is missing and 2 others [are] bogged down with seaweed.” The experiments with these sculptures illustrate Mary’s ethos of commitment without attachment that she practiced throughout her life of making.

Windmills and Other Wind-Blown Sculptures

In addition to out on the lake, up in the trees was another area of Mary’s site that hosted an ever-evolving exhibit. Over the years, different variations of wind chimes and driftwood carvings hung from the trees—the aforementioned red fish started in the trees (and was eventually mounted on the eastside of the house as you can see today). Specifically, the late 60s and early 70s had a lot of tree mobile movement because this was when Mary’s original fence (pictured above in The Herald article) was being targeted for theft and vandalism, so she moved her red fish and fence carvings high enough so local kids could not reach them. What destruction the kids could not accomplish, the wind would eventually do. In April of 1970, she wrote that she was “up and down ladders quite a lot” hanging and rearranging her downed tree mobiles.

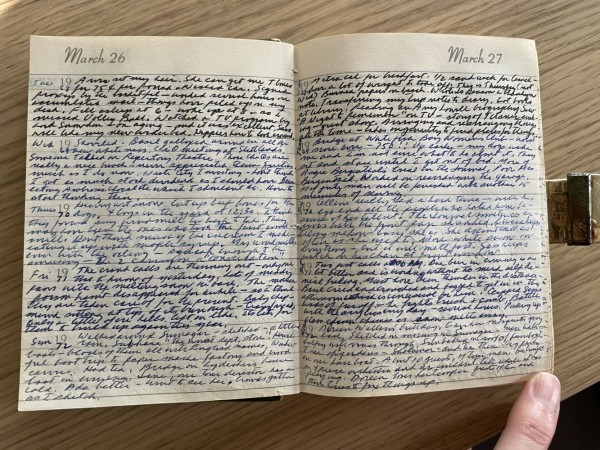

Since there are no sculptures hanging in the trees today or windmills in the yard, Mary’s diary entries regarding the aural qualities of her mobiles and windmills provide a useful window into the soundscape of the site. As you can see from this photo that I took in residency, she wrote five lines per day in her five-year journals:

March 26 and 27 from 1968-1972. Photo by author, 2023

She practiced diligence and discipline with her daily journaling routine, thus her entries provide an incredible amount of context for the conditions of her site. In the last line from Mary’s diary entry on March 26, 1970, she writes “My windmills – even with the oiling – squeak enough to be amusing – the 2 carry on a ‘conversation.” Four days later she adds, “Enamored of my squeaking windmills – as though something living, breathing, out there and it makes me chuckle.” During this five-year period, she reports frequently on the noises coming from her “living, breathing” windmills and clanking chimes. These cacophonous conditions contrast heavily with my residency experience; the lapping of the waves never ceased while I was there, so beyond that rhythmic white noise, the site was profoundly quiet.

Weathervanes

Her army of weathervane sculptures added to this racket as well. This series of sculptures began appearing in her diary in April 1977 when she wrote, “Planning a fish weathervane for the top of house – always liked weathervanes.” A few weeks later, she semi-successfully put up her first fish weathervane, but strong winds blew it down within three hours. Five days later, she put the weathervane back up, but this time with “20 screws.” So after some trial and error, she finds a reliable installation method. Although, in April, she reports that in the middle of the night she had to climb up onto the roof twice to check on all the noise they were causing. The weathervanes and their commotion are a great example of a set of sculptures that are not preserved on site but can be viewed at the JMKAC in their Art Preserve. In the first photo posted below, you can see the weathervanes screwed into the roof; in the second photo below, the weathervanes are seen as displayed at the Art Preserve.

Photo courtesy of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

Detail of the Mary Nohl installation at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center's Art Preserve. Photo by author, 2022

Conclusion

Photo: Lisa Stone, 2007. Courtesy of SPACES Archives.

Through this photo by Lisa Stone, we can see that the weathervane sculptures were screwed into the roof on the northwest side of the house. Therefore, the weathervane convening would theoretically be visible from the road while you’re peering through the fence trying to get uninterrupted views of the site. Mary’s windmills also would have been a dominating presence– she reports on March 5, 1970, that she “Got my big windmill up – looks great – see it way down the road.” So, whether you are a frequent Mary Nohl house stopper-byer or you still have yet to make your first pilgrimage, bring your imagination and try to picture and listen for her swinging mobiles, windmills, and weathervanes as you admire her already replete and whimsical world.

Acknowledgements

My profound thanks is owed to Alex Gartelmann and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center for being the most gracious and brilliant hosts. In particular, Alex’s transcriptions of Mary Nohl’s diaries proved invaluable– his diligent work across the board has made researching her work incredibly accessible and infinitely exciting. Finally, I am endlessly grateful to Mary Nohl; her legacy has had an extraordinary impact on my thinking, learning, and being in the world.

Bio

Grace Hayes is a PhD Candidate at the University of California, Davis and is working on a dissertation currently titled “The Ecological Everyday in Artist-Built Environments and Postwar Poetry.” In it, she uses postwar poetry as a heuristic to examine how the embedded ecology of art environment sites materializes in the art form. She is originally from Milwaukee, Wisconsin and grew up going to the “Witch’s House,” so her first chapter on Mary Nohl’s artistic legacy holds a special place in her heart.

Post your comment

Comments

Cassandra February 18, 2025

The idea that some of her sculptures were short-lived yet still left a lasting impression raises an important question—should art be preserved at all costs, or does its transient nature add to its meaning? Her approach reminds me of how architectural landscapes evolve, with some creations standing the test of time while others disappear, making way for new developments, this concept is especially relevant in places like Dubai, where innovation and reinvention shape the city’s skyline. Projects by Danube Properties projects exemplify this transformation, introducing modern living spaces that redefine urban lifestyles. Just as Nohl’s art continues to inspire despite its impermanence, Dubai’s architectural evolution reflects a similar blend of creativity and constant change.

Shari Tuska January 18, 2025

Thank you for sharing your process and work! Its seems, while in your process, you centered in on a part of Mary's process of creating by acknowledging its existence and engaging a conversation (the chuckle) with it (the work). “Enamored of my squeaking windmills – as though something living, breathing, out there and it makes me chuckle.” It is the "as though" that holds the wonder ... Brava Grace