Museo de la historia y de la vida (Museum of History and Life)Maximo Rojo (1912 – 2006)

About the Artist/Site

Máximo Rojo was one of eight children born to a family of subsistence farmers in Cortes de Tajuña, a tiny village that by 2009 was home to only thirty-three inhabitants. His father died when he was six and his mother was left to care for the children; Rojo never had the opportunity to attend school: he helped in the fields starting at age seven and by age fourteen was in charge of a flock of sheep. He did not learn to read until he entered the military to perform his required service, between age eighteen and twenty, teaching himself from a scholastic encyclopedia that emphasized geography and history. In retrospect, it appears that this was the spark that shaped his worldview and inspired his interest in communicating what he had learned to others.

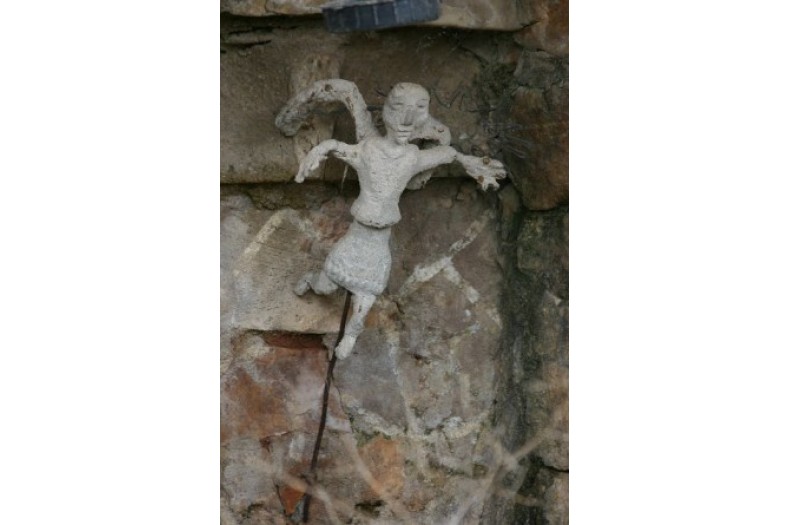

Although he had never before evinced any interest in art, Rojo began building a “museum” with a sculpture garden on the site of his fruit orchard after he retired in 1979 at the age of 67. Working quickly and feverishly, he ultimately packed over 300 discrete figures, animals, and forms into this small, irregular plot of 8,815.6 square feet (819 square meters), about one-fifth of an acre, once on the outskirts of the village but now sandwiched between several newer two- and three-story apartment buildings. The impact of this sculpture garden is overwhelming: around 300 figures, animals, and objects crowded together with no apparent sense of organization, so that contiguous works might provide a reference to events that happened centuries apart, or mythological or literary figures might be installed next to bona fide historical characters. He defended his efforts by inscribing a Spanish proverb on the entrance wall and on more than one of his pieces: “Obras son amores y no buenas razones [I do what I do for love, and I do not need another reason].”

Constructed from unpainted concrete over steel wire, sticks, or found object infrastructure (including ceramic pots and soccer balls), in general Rojo’s craftsmanship was poor and he seems to have had little understanding of a suitable way to construct works so that they might withstand the rigors of the cold, humid winters and hot summers of Spain’s central plains. During my first visit, only two years after Rojo’s death, the field had already begun to take on the look of a surreal cemetery, with concrete body parts scattered on the ground and many of the works in a marked state of deterioration. Although some of this was certainly a result of vandalism, there is no doubt that the rapid decay of the site is also at least partially due to the artist’s unconsciously careless fabrication and assembly of the works.

His works run the gamut of local figures and scenes, including animals tilling the soil and at least two self-portraits of the artist and his wife. There are also well-known historical figures, such as Christopher Columbus, Magellan, the royals Fernando and Isabel, and El Cid; literary references, including Don Quijote and Sancho Panza; representations of animals and birds; and many religious narratives, including Adam and Eve, Noah’s Ark, a Nativity scene, and the Last Supper. More conceptual works were created as well, such as the three figures representing Fe, Esperanza, and Caridad [Faith, Hope, and Charity] at the entrance to the site, enhanced by textual admonishments for visitors to abide by the Golden Rule and treat each other well. Several large architectural-like structures are also on display. Taken together, the varied sculptures—often labeled with anecdotes or exhortations, numbered as if they were “chapters,” and identified with metal wire or carved inscriptions—range in size from several inches to several meters, and provide a universal encyclopedia of popular knowledge. And although the works were, at least at one point, organized thematically according to the encyclopedias from which he learned to read, the overall impression is one of chaotic excess.

Disparaged by the local community during Rojo’s artistic life, the village has now closed his “museum,” although one may ask at the city hall for entrance, which is occasionally granted. And although in 2008 the village had toyed with the idea of developing a “tour” of local art sites (the House of Rock by Lino Bueno is also within city limits), the economic crisis of more recent years has effectively stymied that idea. With each passing season more works degrade or are vandalized, and there is no existing plan to either open the garden to visitors or to address the severe conservation needs of the sculptures.

The artist also ornamented his home, several blocks away from the sculpture garden. The interior has been gutted (in preparation for future conservation, it has been said), but numerous smaller sculptures are easily visible around the exterior façades and in a small yard area at the rear.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2014

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Alcolea del Pinar, Castile-La Mancha, 19260

es

Latitude/Longitude: 41.0381144 / -2.475252

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.