La Casa de las Ranas (The House of Frogs) / Chapel of Jimmy Ray GalleryAnado McLauchlin (1947 - 2021)

Extant

Temazcal 3, La Cieneguita, Mexico

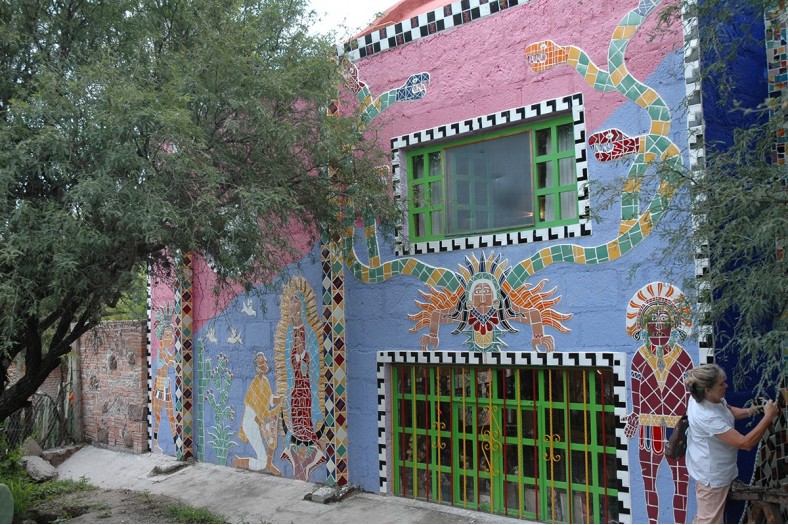

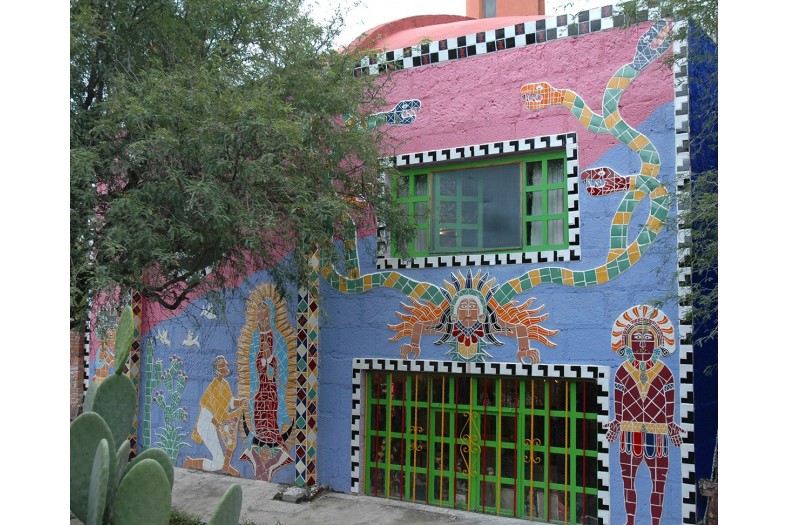

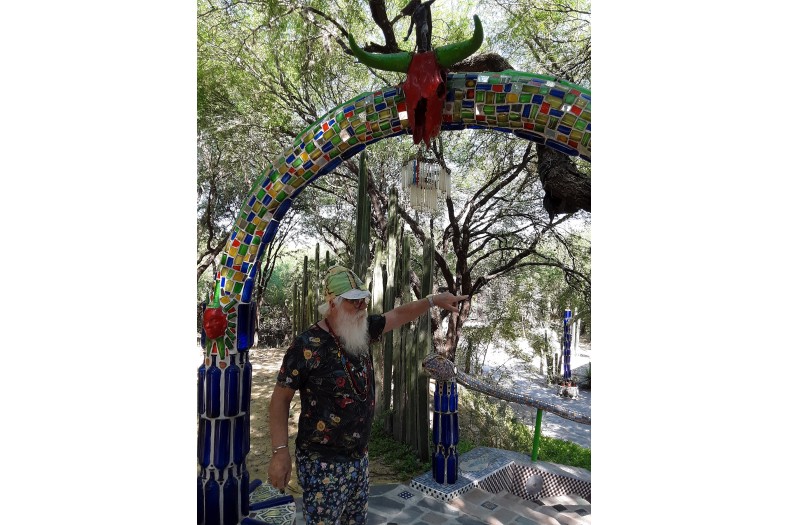

Potential visitors are advised to take the tour, for little of the art environment is truly visible from the road except for the brightly-painted wall surrounding the property, painted with frogs, snakes, and native motifs.

About the Artist/Site

James Rayburn McLauchlin III was born on May 24, 1947 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma to a father who was a doctor and a mother who stayed at home to care for her family; although the couple had been without artistic training, they encouraged their only son’s interest in art. He lived at home, served in the navy, and then entered the University of Oklahoma at Norman, where he intended to pursue a career in visual art. However, he quit school after one year, disheartened by his professors’ comments that his work was too decorative, preferring instead to explore his artistic consciousness with the help of mind-altering psychedelics and meditation instead of academic theories and classes.

He spent the following two decades traveling the world and working as a part-time delivery boy, waiter, bartender, Christmas Santa, chimneysweep, actor, and more, odd jobs that provided him with the bare minimum of financial resources such that he could spend his free hours working on his art. Among his stops were New York City, where he drove a cab from 1971 to 1981 and involved himself in the Gay Liberation Movement and the performance poetry spoken word movement; and numerous visits to Asia – and, in particular, an extended stay in an ashram in India – between 1978 and 1989, during which time he was re-christened Anado by the Indian spiritual teacher Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (Anado means “No Sound” or “Silence” in Sanskrit). He also lived in the Sacred Valley of the Incas in Peru and in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he fabricated decorative furnishings out of a studio in Sausalito at the same time as he worked as a landscape gardener.

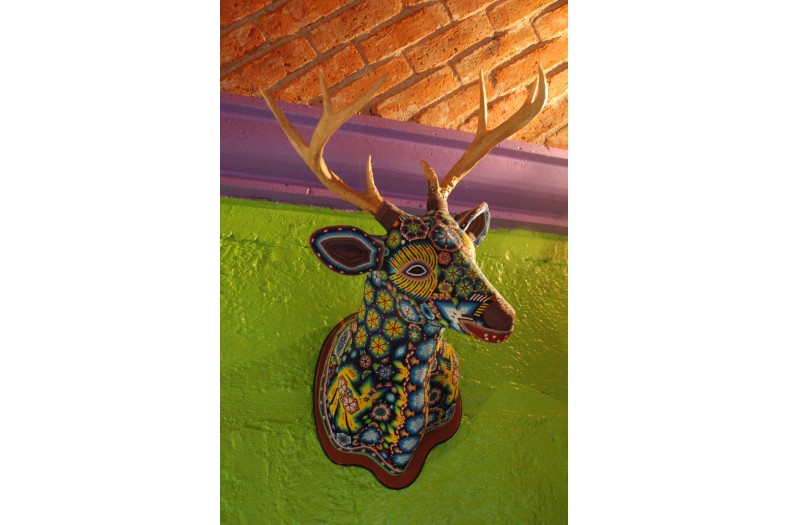

In addition to developing his aesthetic simply by keeping his eyes open during his travels, McLauchlin was also an avid museum goer, and was particularly inspired by an exhibition of Australian aboriginal art that he saw in San Francisco, as well as exhibitions of the works of Native American artists. The aboriginal exhibition, in particular, inspired him to start making dot paintings, something that he continues to this day, although he has become more renowned for his mosaic work – discrete freestanding and wall-mounted works as well as architectural decoration.

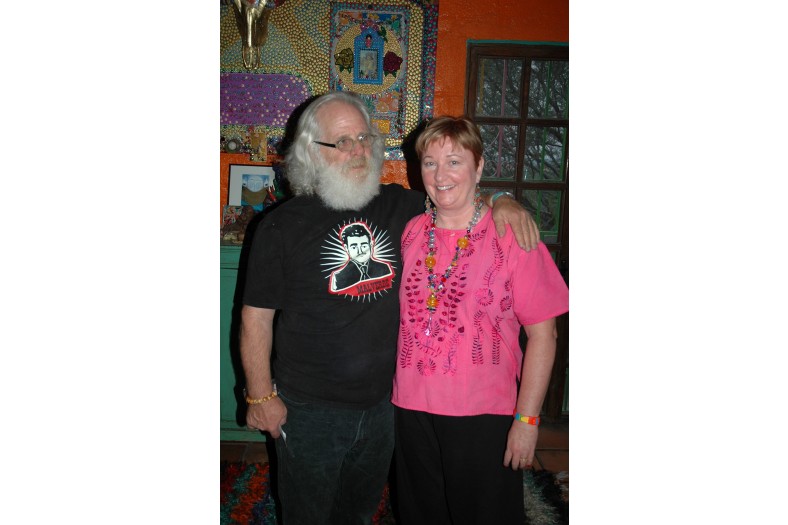

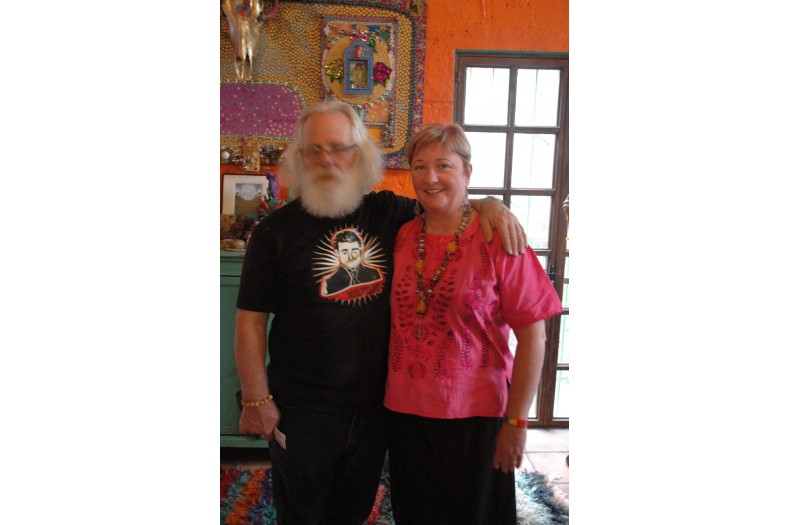

In 1998 he met his future husband Richard Schultz, a 37-year teacher of history and Advanced Placement art history at Notre Dame High School in San Mateo, a small city south of San Francisco. By that following year, McLauchlin finally felt sufficiently financially secure to retire from his various odd jobs in order to concentrate solely on his artwork. In 2001, he and Schultz, who had recently retired from teaching, decided to vacation in San Miguel de Allende, a charming enclave – and now UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site – that has long been considered an art center, particularly for expatriate North Americans from the US and Canada. They thought that perhaps they would rent a place for one year to see how they liked it, but within two weeks they had found and purchased the property that would become the art environment known as the Casa de las Ranas. Located in a small community between San Miguel de Allende and the village of Atotonilco,[i] the 2.5 acre property included a gutted two-story stone house full of scorpions, a few deteriorating outbuildings, and a lot of brush.

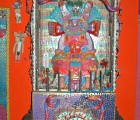

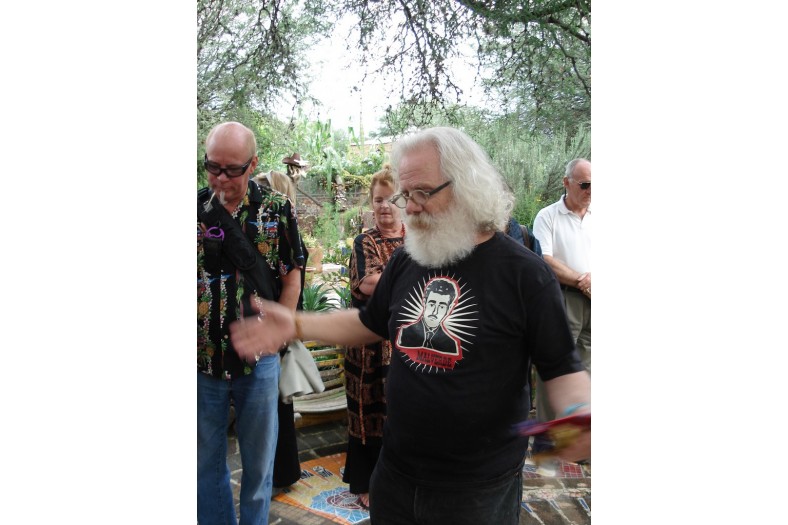

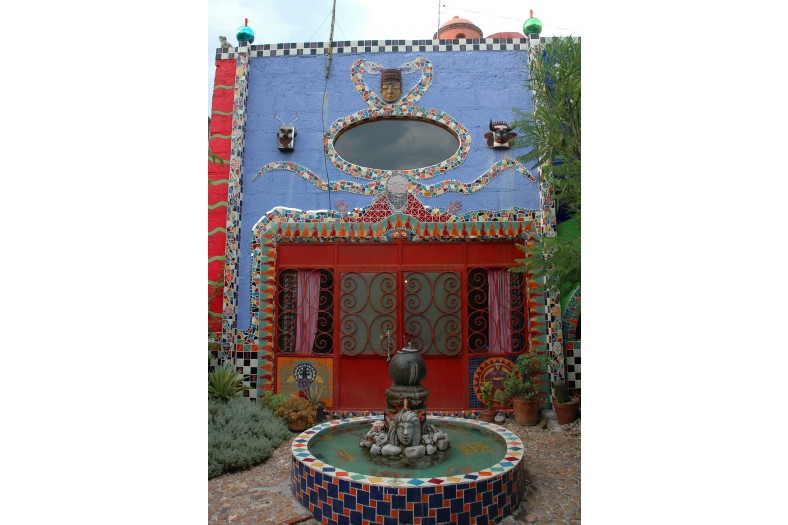

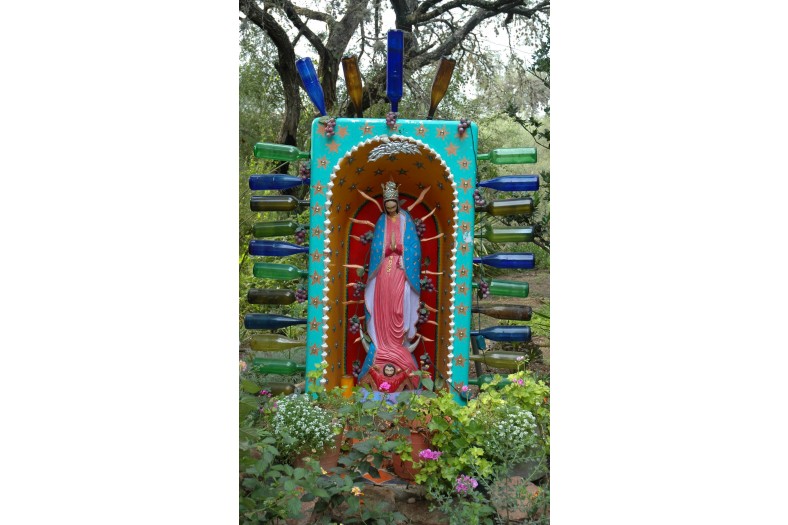

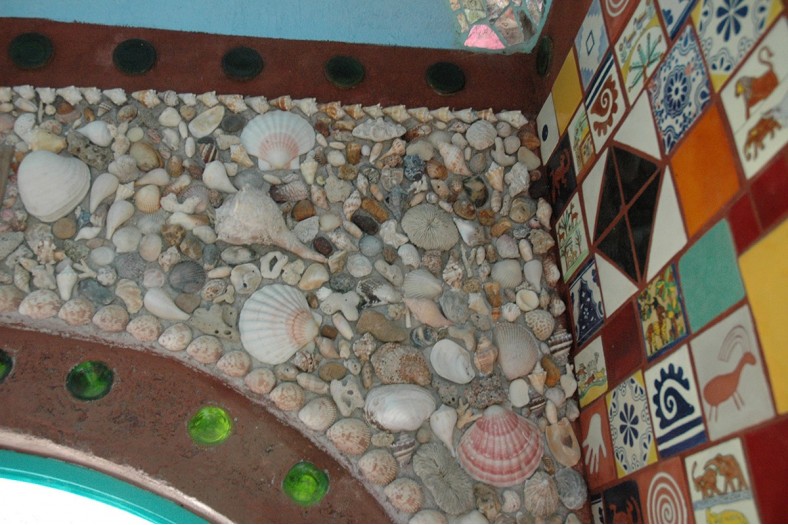

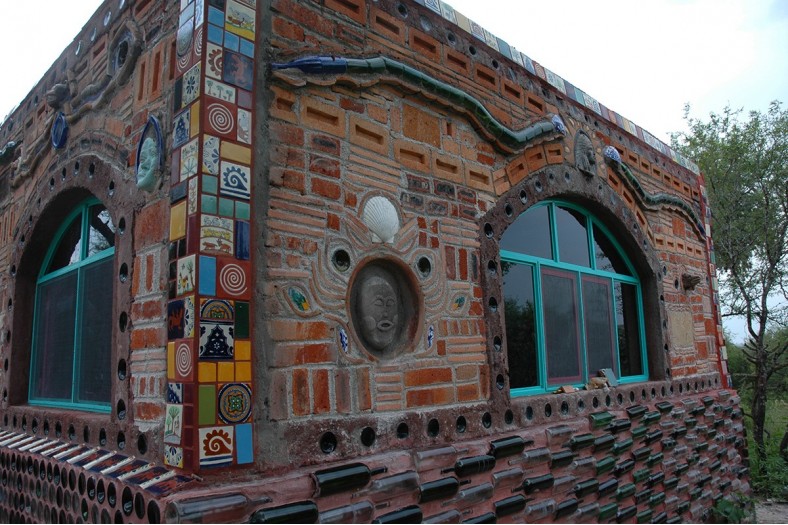

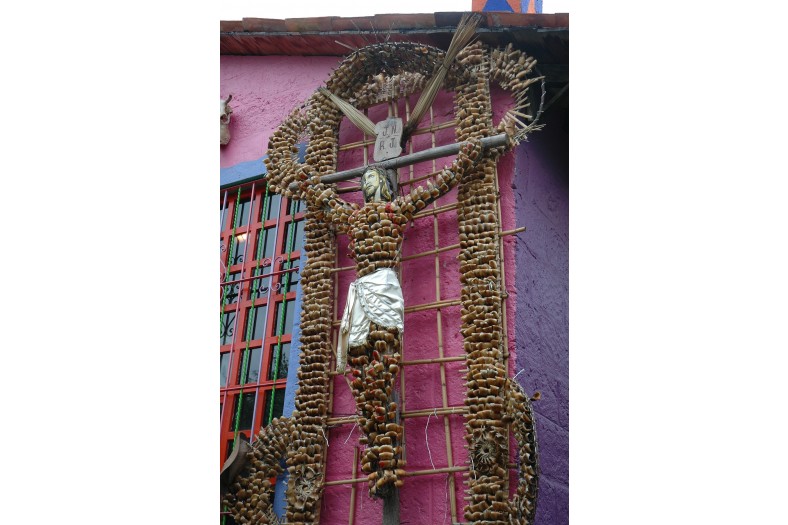

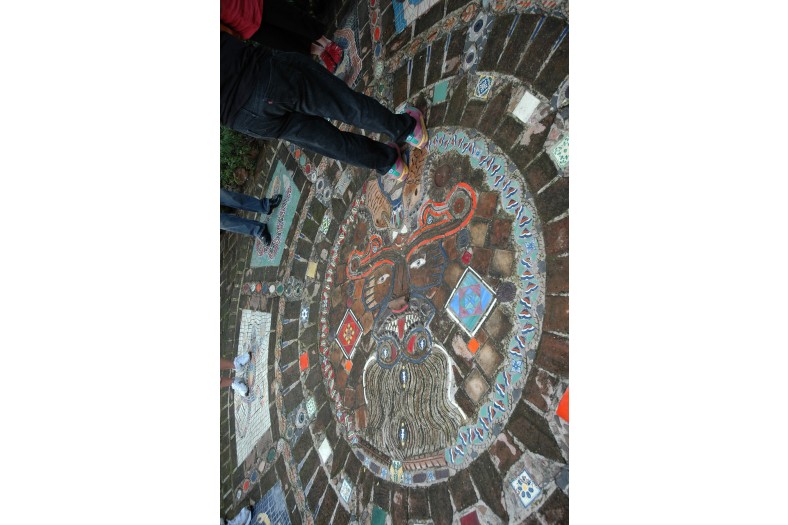

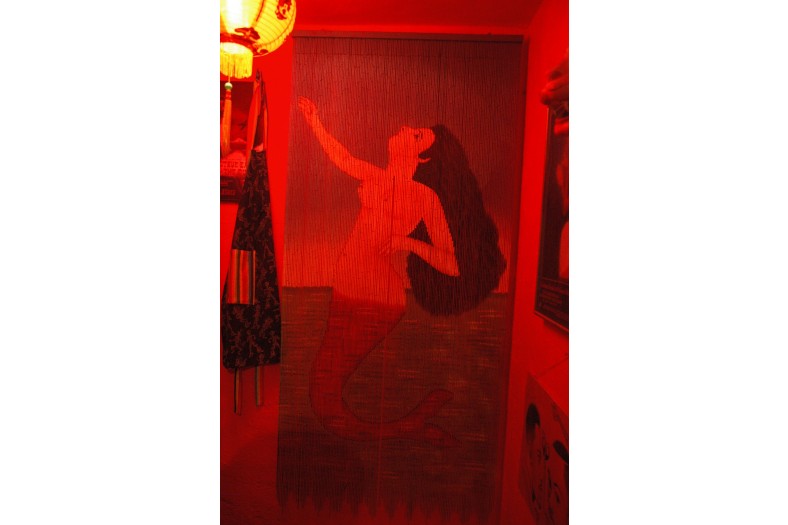

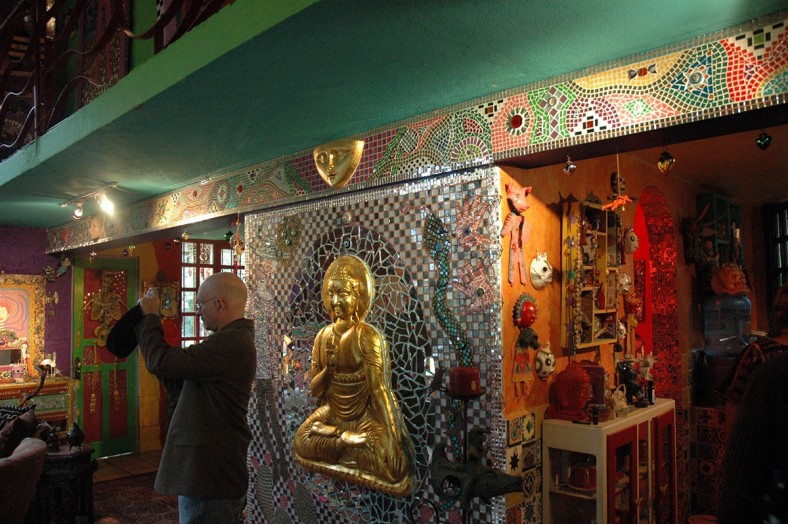

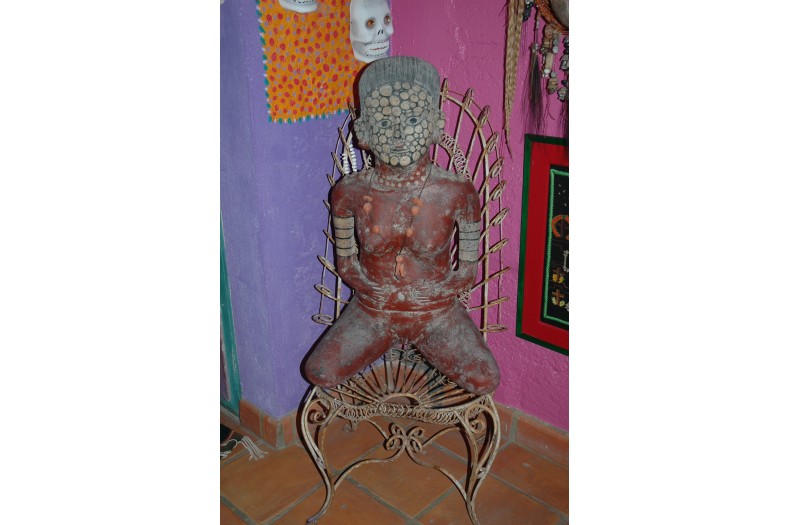

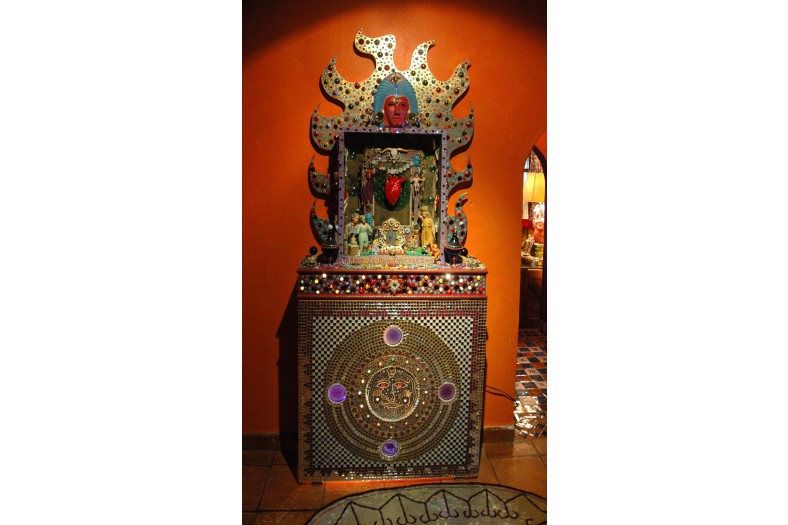

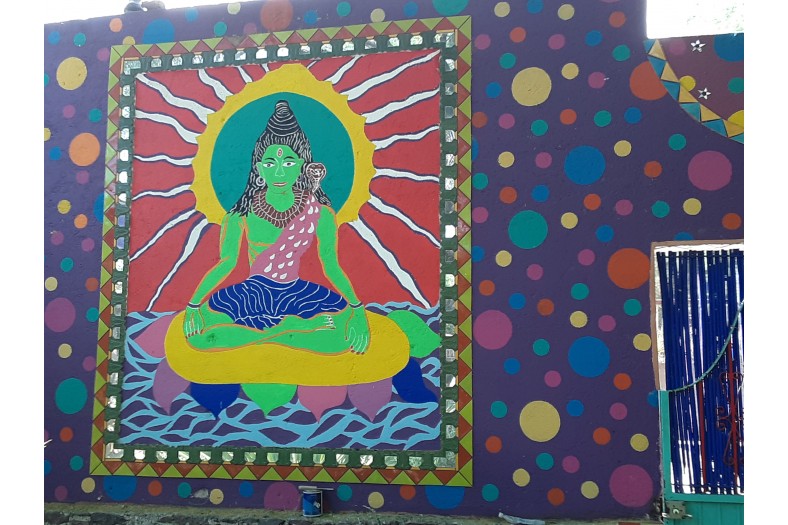

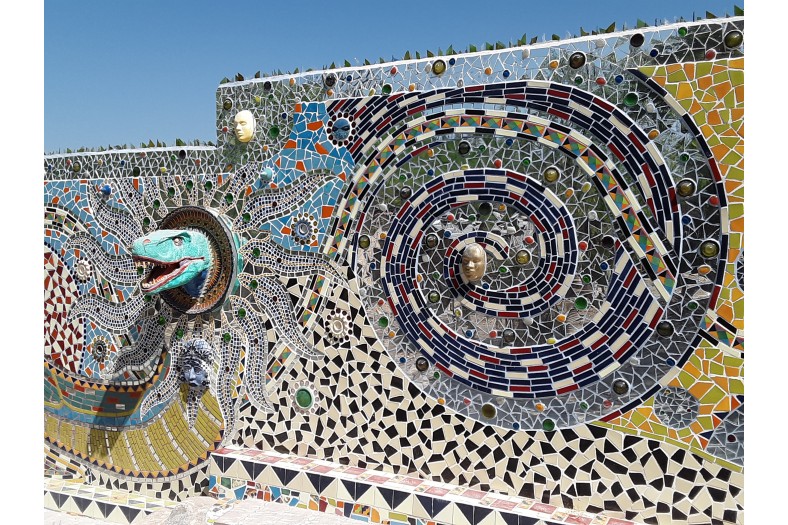

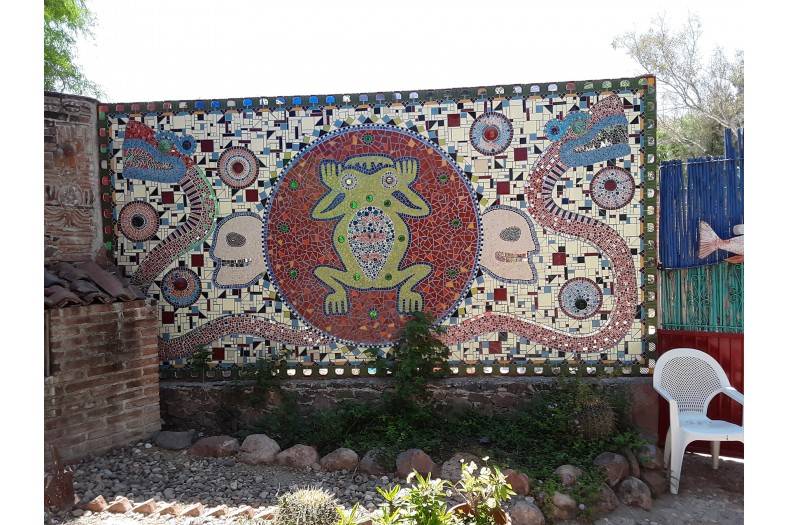

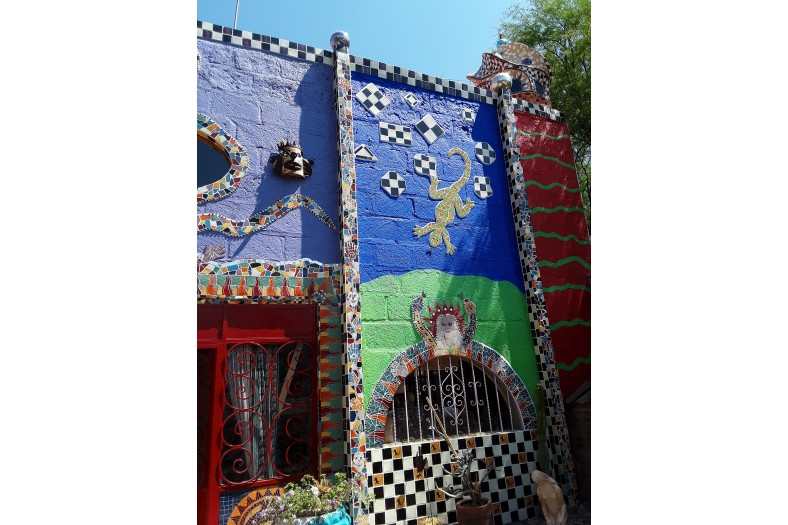

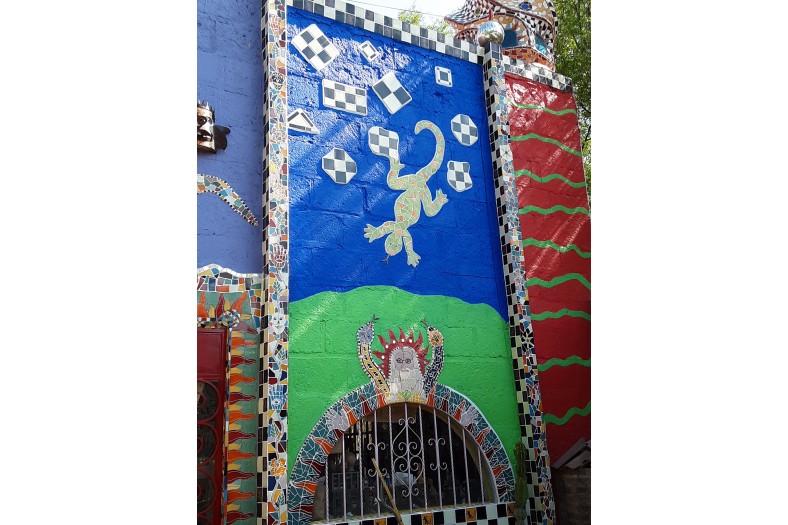

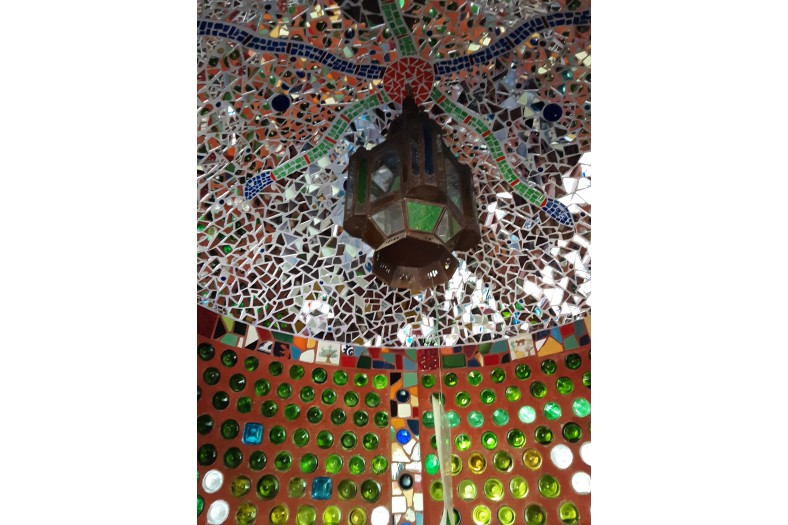

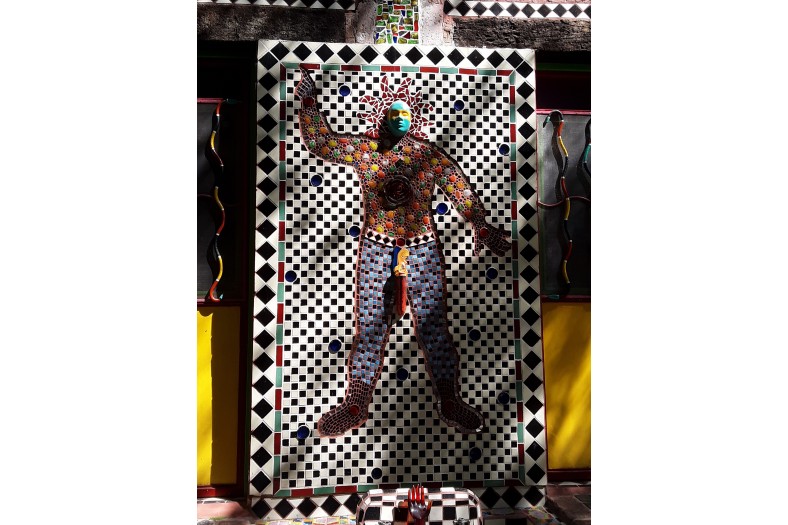

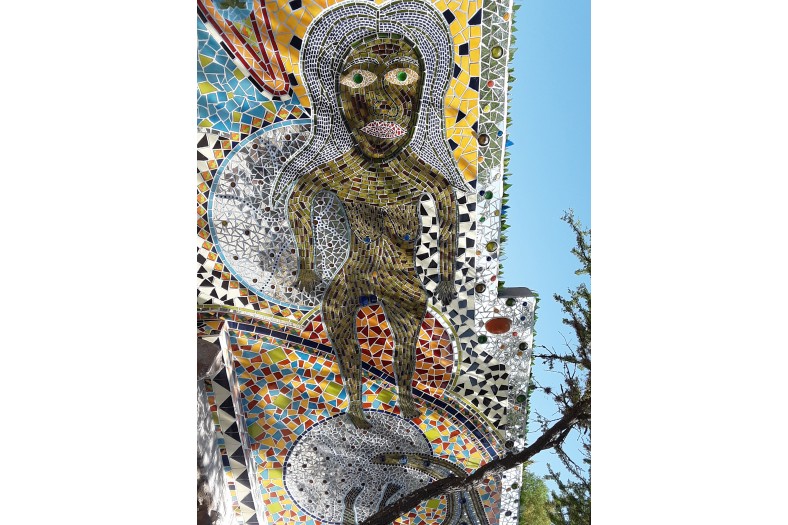

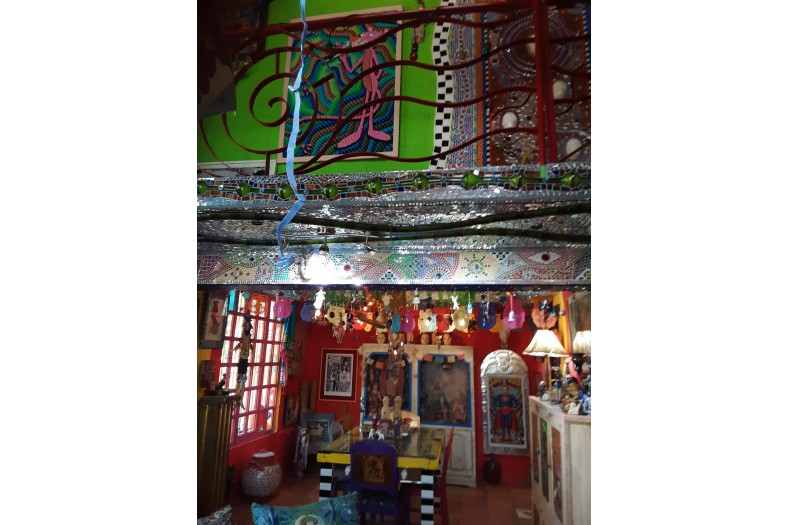

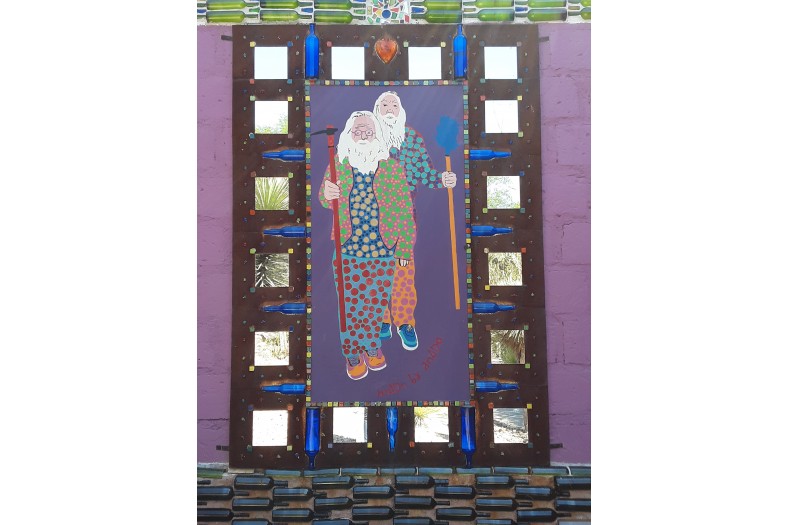

Feeling financially pressured, McLauchlin felt that he needed to begin to work immediately, so he began doing mosaic and jewelry work on commission for a wide range of clients. Yet as he did so, and as his work became more renowned, he also began to transform the property on which he and Schultz were now building a new life. Dedicating it to “the Outlanders of the world, those who have chosen the road less trodden,” they renovated and added on to the home such that it has become a classic example of horror vacui, with no space, inside or out, left unadorned. Mosaic images created from mirrors, tiles, ceramics, and found objects riff on Native American and Mexican motifs but also reveal personal homages to people who have been important in his life: he embraces the legacies of his parents, memorializing them with walls that include their portraits; there are also numerous self-portraits of the long-bearded McLauchlin and Schultz, found all around the property, in both interior and exterior spaces and in all scales and colors. Brightly-painted walls and ceilings are hung with collected artworks of all kinds, from local indigenous festival fabrications and crafts to paintings and prints by friends, traditional paper cut-outs, dolls heads, masks, saints figures, animal skulls, living plants, and more. Religious images include Buddhas, the Hindu elephant god Ganesh, and the nationally-venerated Virgin of Guadalupe. Much of the work is nominally spiritual; McLauchlin has commented: “Lo que yo hago a un nivel poético es tratar de combinar todos los sistemas de creencias, todos los caminos y mostrar que en realidad sólo hay un camino, existen diferentes formas, decoraciones pero hay un sólo camino hacia donde todos vamos [What I do on a poetic and metaphorical level is try to combine all of the different belief systems and all of those spiritual roads and to show that in reality there is only one road; it exists in different forms and with different decorations but there is only one sole road toward which we all travel].”[ii] Regular use of mirrors – both in broken pieces of trencadís as well as solid wall coverings – complement the innumerable collections and preventing them from overwhelming with textures, colors, and forms.

A 2008 New York Times article brought even wider attention to McLauchlin and his work, and he became the fulcrum of a small group of local (mostly expatriate) artists. He began building the Chapel of Jimmy Ray Gallery in late 2011, funded in part through a Kickstarter campaign; this construction is now used for the exhibition of the work of other painters and sculptors in addition to his own. While he has described Jimmy Ray as “mythical character,” he clearly takes inspiration – if not origin – from his own given name as well as that of his father and grandfather. This building, inaugurated on February 12, 2012, is also adorned inside and outside with paintings, assemblages, and mosaics. A psychedelically-inspired black-and-white painted abstraction on the ceiling in the main gallery space surprisingly does not seem to fight with the brightly colored works on display; instead, it complements them with its similar intensity.

Other outbuildings include an outhouse – a round bottle house with elaborate finials so thoroughly decorated that it is hard to believe that it and its composting toilet are functional, although they are – and Casa Kali, a multifunctional building originally built with the intention that a dear friend might move in; she has since passed and the space is now used to display assorted artworks, albeit in a less formal setting than in the Chapel of Jimmy Ray Gallery. There is also a spacious and well-lit studio space that will become a memorial to the various dogs that have passed through the lives of McLauchlin and Schultz as well as, increasingly, those of their friends. The exterior sheathing of this one-story building is still very much in process, but already features portraits of some of their dogs, interspersed with bottles whose necks and mouths protrude into the interior. Within, McLauchlin, his main assistant Carlos Ramírez Galván, and other long-time helpers work on long tables, assembling mosaics from the boxes and bins of raw materials stacked around the perimeter.

Stairways bounded by writhing serpentine mosaic reptiles, bottle fences, freestanding altars, a monumental smiling head with fiber mustache and beard constructed by neighbor children out of twigs and branches, and a branch fence ornamented with painted cat food cans are among the works that grace the spaces between the constructed buildings. (McLauchlin designs all of the buildings on site, and then closely monitors the construction work of 3-6 members of the Ramírez family; he calls them all “Team Groove.”) Shells, stones, all kinds of found objects, local Talavera tiles, sea shells, Mardi Gras beads, dominoes, and more round out his palette, fitted together in images that are improvisationally conceived without the use of preliminary sketches or maquettes. Most of the mosaics are created in-situ, rather than being fabricated in the studio and then moved out to be mounted.

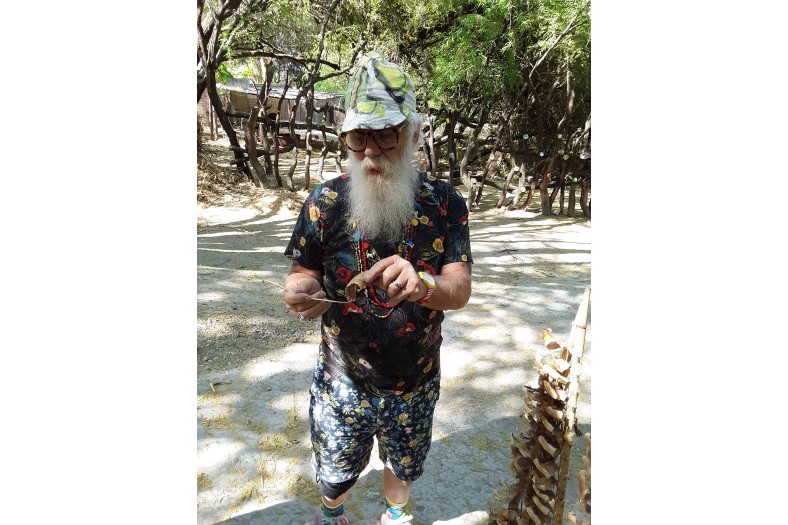

A rear “garden,” in which currently little is growing except cactus, is framed by an elaborate mosaic wall, the Kismet Street, rising some 2-3 meters (6 or more feet) tall and 150 meters (almost 500 feet) long (a flourishing vegetable garden, tended primarily by other members of the Ramírez family, is located elsewhere on the property). This work features an evolving series of images, from portraits of loved ones, political statements (“Dump Trump”), and stylized indigenous, zoomorphic, astral, human, and floral motifs often redolent of his dreams. The craftsmanship is meticulous, the colors are saturated and bold, and the imagery is both creatively developed and cleverly integrated. It should be noted that both McLauchlin and Schultz dress in a manner consistent with the artwork on display, wearing riotously colored and patterned clothes, ornamented with his handmade jewelry, and complemented with elaborate tattoos, bright socks, and multicolored shoes. They are both the perfect counterpart to the art environment itself.

As McLauchlin continues to work on the site, which he believes will always be a work in progress, as well as on his ongoing commissions, members of the public are welcomed to visit with prior appointment. Currently, the artist offers tours of the site, with a requested donation, three times weekly; he could fit in more, he says, but it takes too much time away from his artwork. He does enjoy the interaction with his visitors, however, because it gives him the opportunity to encourage them to lighten up and enjoy life more, and to look inside themselves to find their own creative expressions. Potential visitors are advised to take the tour, for little of the art environment is truly visible from the road except for the brightly-painted wall surrounding the property, painted with frogs, snakes, and native motifs.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2019

[i] Atotonilco is renowned for the mural paintings in the Santuario de Jesús Nazareno painted by Antonio Martínez de Pocasangre over a thirty-year period. They date from the second half of the 1700s

[ii] Quoted in http://www.atencionsanmiguel.org/2015/05/08/anado-mclauchlin-creatividad-color-y-diversion/. [This article has since been removed from the website.]

Update: Anado McLauchlin passed away April 4, 2021 after a brief battle with colon cancer. His husband Richard Schultz continues to live at and maintain Casa de las Ranas.

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Temazcal 3

mx

Latitude/Longitude: 23.634501 / -102.552784

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.