The Rudolph Grotto Father Philip J. Wagner (1882-1959)

Extant

6975 Grotto Avenue, Rudolph, Wisconsin, 54475, United States

1919-1959

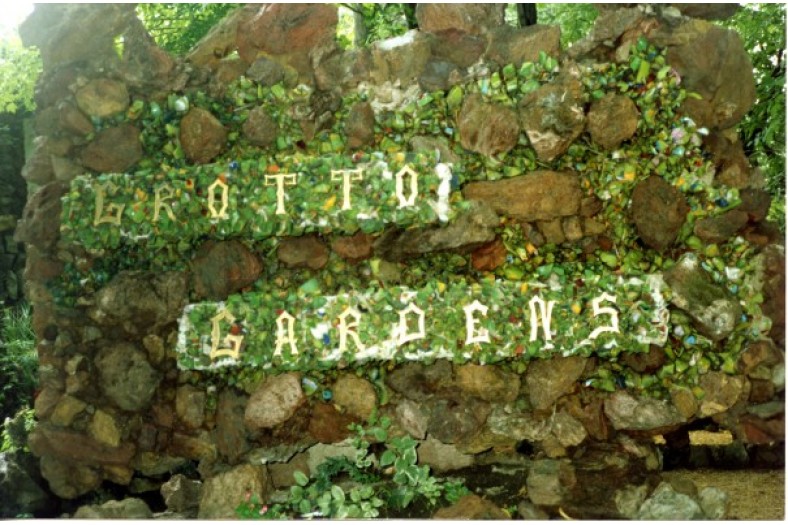

The Grotto Gardens are open year round for all to enjoy. The Gift Shop and Cave are open seven days a week on a seasonal basis from Memorial Day through mid-September. The St. Philip Church Picnic is held at the Grotto Gardens each year on the first Sunday in August.

About the Artist/Site

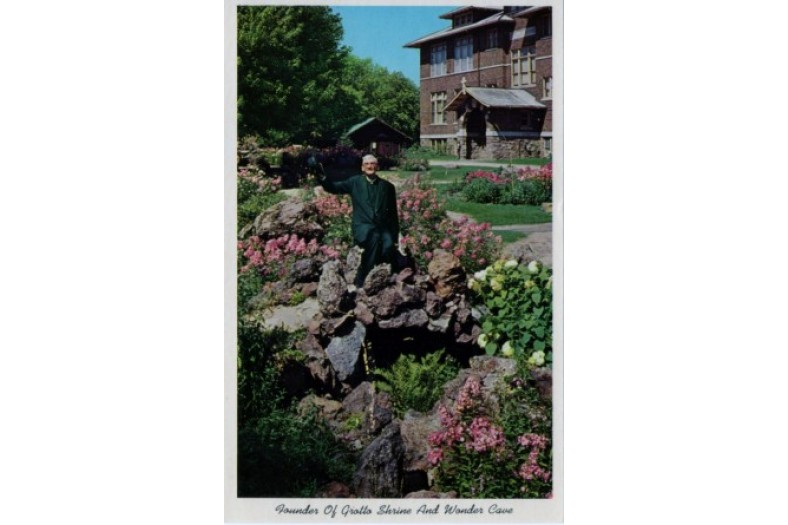

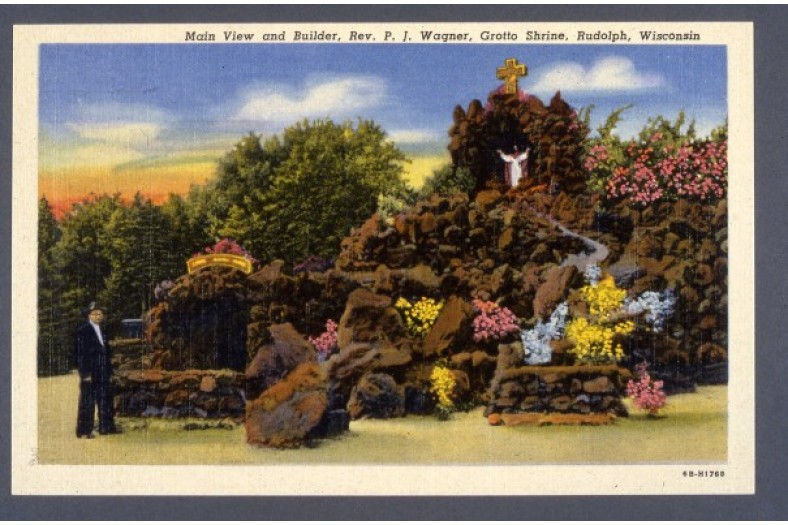

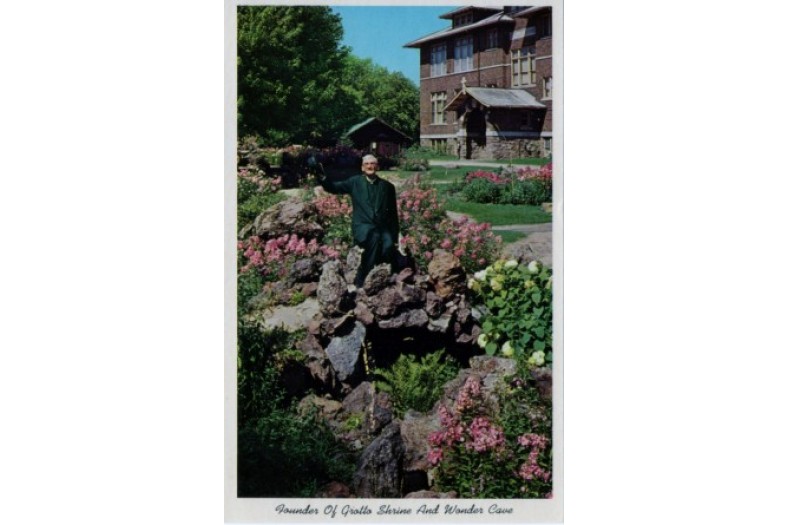

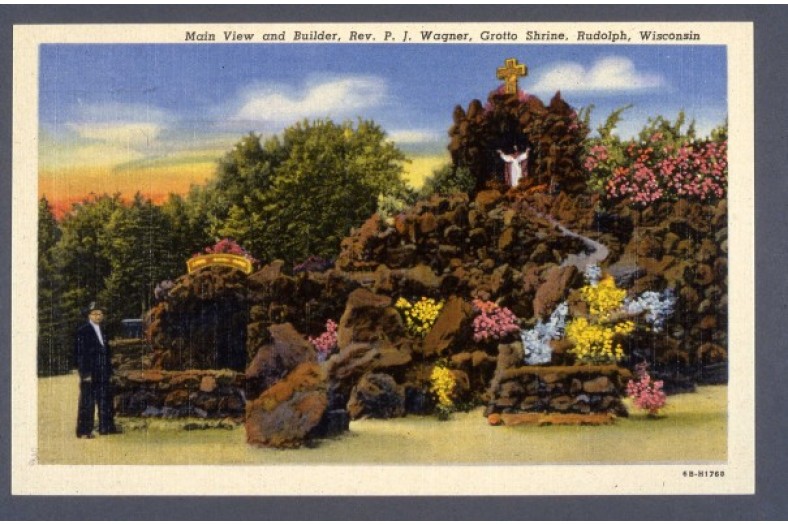

The third monumental Catholic devotional grotto built in the Upper Midwest is located in the small village of Rudolph in central Wisconsin. Less well known than the Grotto of the Redemption by Father Paul Dobberstein (West Bend, IA) and the Dickeyville Grotto by Father Mathias Wernerus (Dickeyville, WI), the Rudolph Grotto is a monumental expression of naturalistic architectural forms made of highly original rock-work and abundant plantings. It was built by Father Philip Wagner, with much assistance from Edmund Rybicki, beginning in 1919 (when the gardens were begun), and officially ending with Wagner’s death in 1959, although work at the grotto—primarily on the landscape—continues to be ongoing.

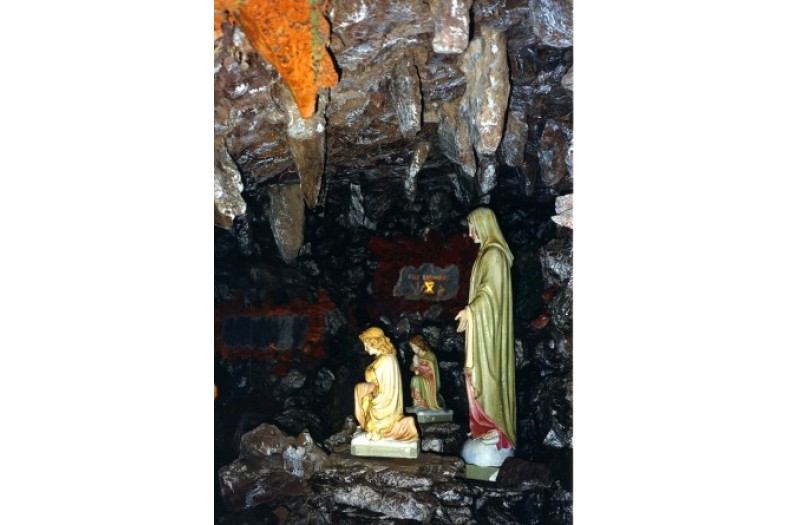

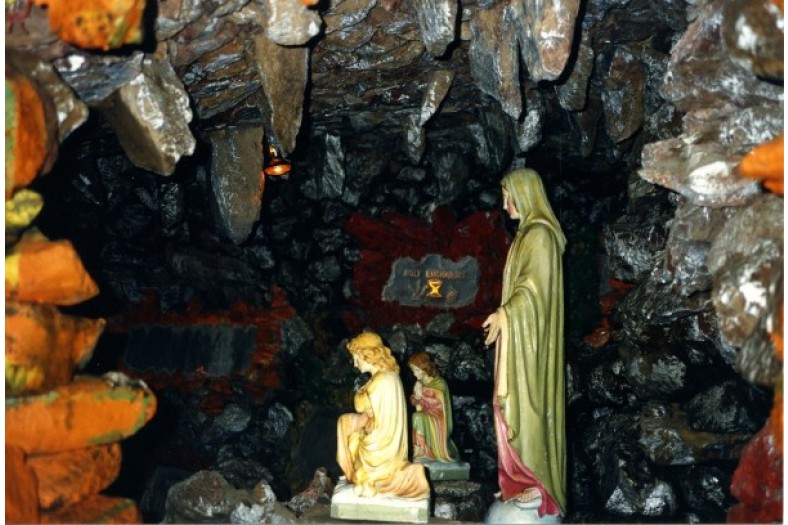

Philip J. Wagner was born in 1882, grew up on a farm in Iowa, and studied for the priesthood in Innsbruck, Austria. While he was still a student, exhaustion led to a physical collapse, so Wagner traveled to France to seek recovery at the renowned shrine at Lourdes. (The cult of Our Lady of Lourdes had spread throughout the world and had attained considerable popularity among American Catholics.) It was there that Father Wagner made his vow: “My health having failed, I prayed devoutly to Mary amidst the quiet and beauty of the place. Should it be restored I promised to build sometime, somewhere, a shrine in her honor. As I took baths in the miraculous water, my condition improved, my courage revived, my strength returned.”

Wagner was ordained, returned to the United States, and was sent to Rudolph in 1917 by the Bishop in La Crosse, Wisconsin with instructions to preach in English and to establish a church and school. The new school was completed in 1920, and Wagner enthusiastically embraced his duties as an educator-priest. But as early as 1919, even prior to the completion of the new school building and nine years before the first actual grotto was begun, Father Wagner began to establish a sumptuous landscape scheme, transforming a nondescript potato field into a labyrinth of garden spaces, and planting dozens of varieties of trees and shrubs throughout. The rigorous landscaping project was well under way by the summer of 1927, when Wagner made his first attempt at fulfilling his promise to build a shrine to Our Lady of Lourdes.

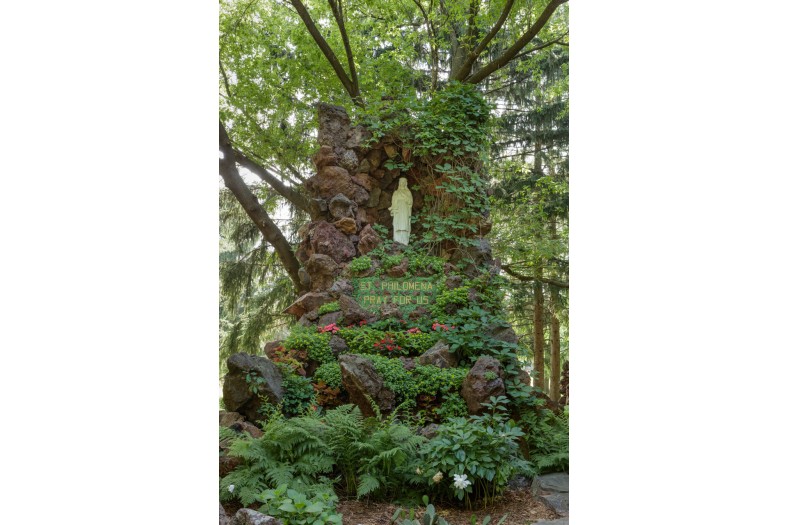

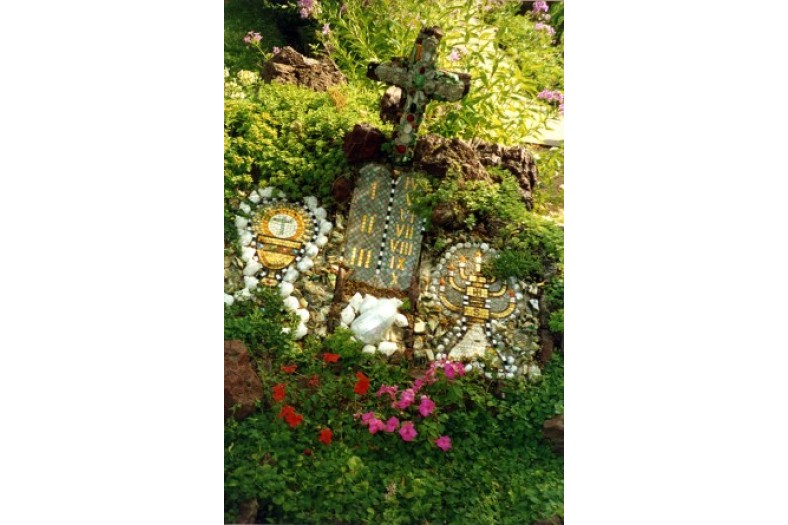

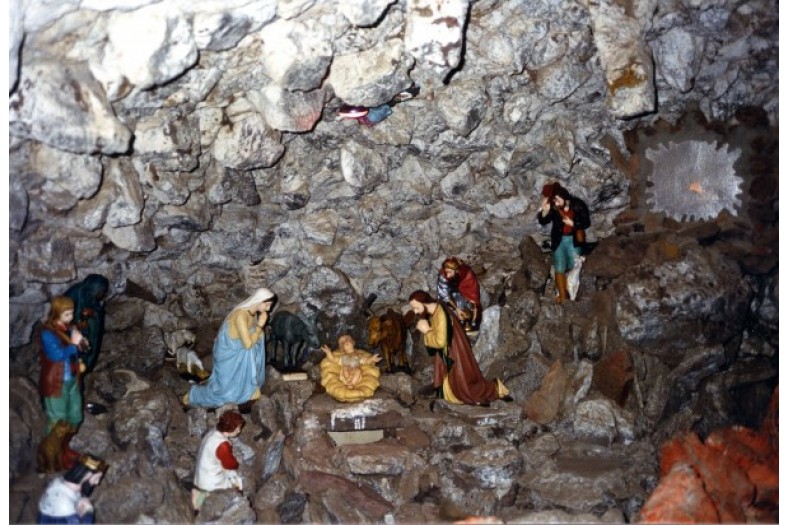

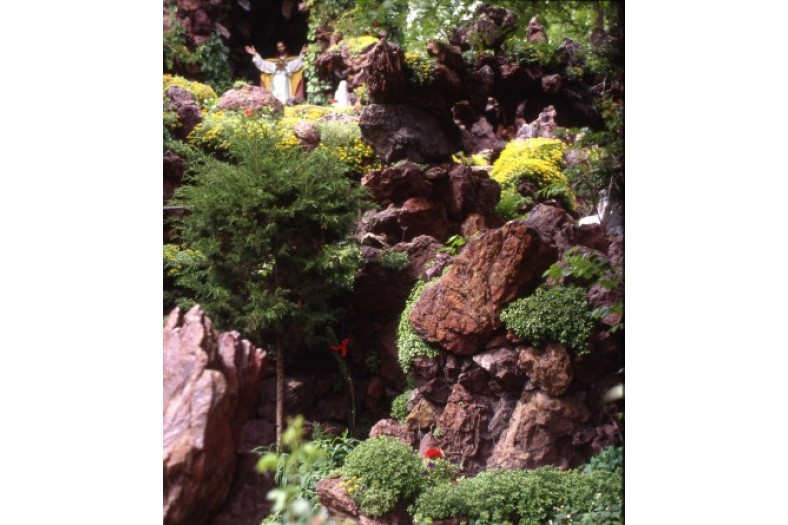

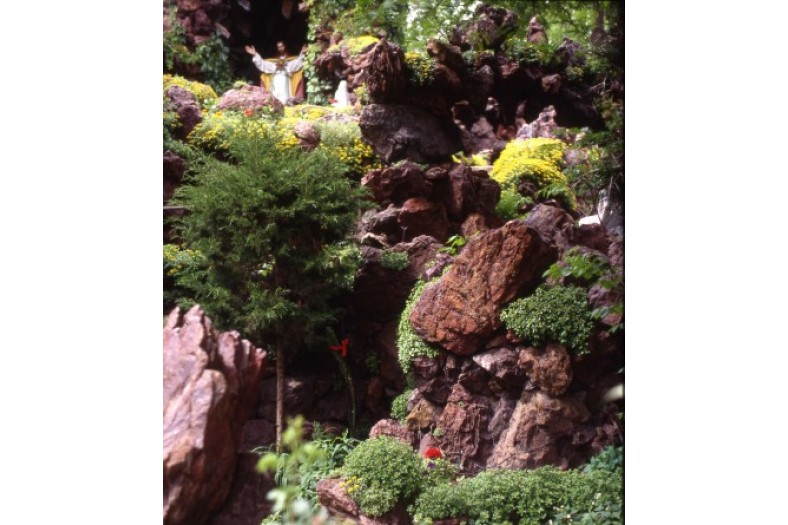

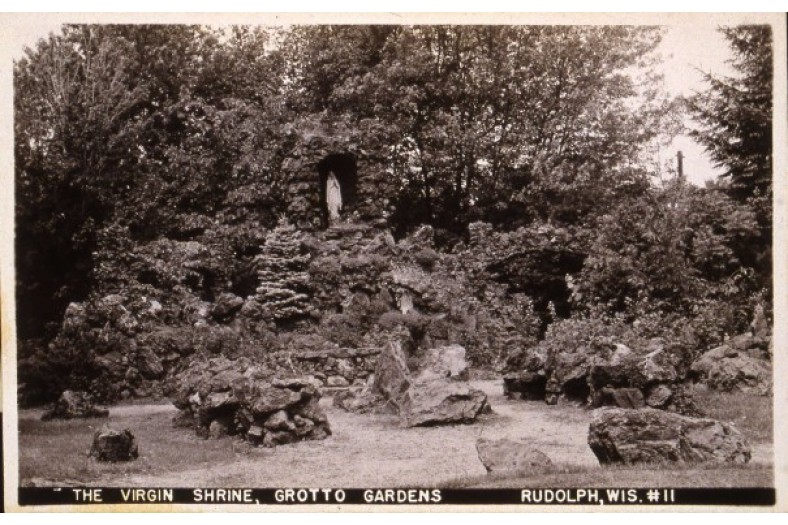

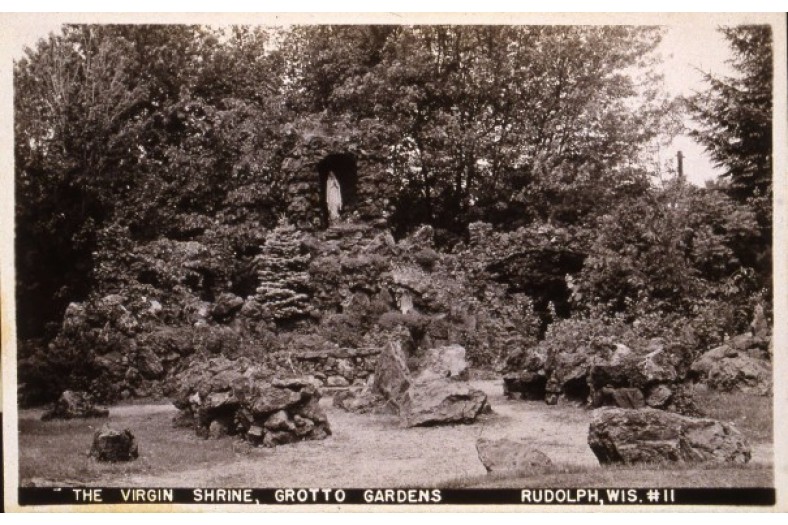

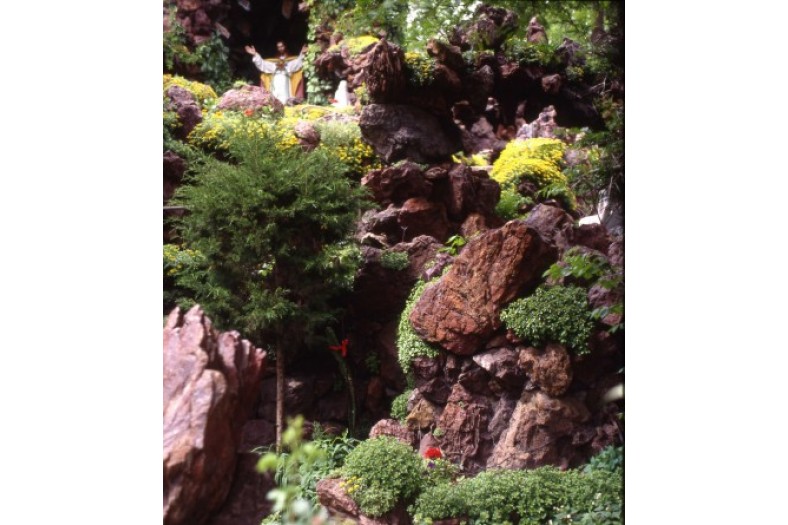

He began intuitively, making piles of rocks without securing them with mortar, and the structure failed. In the fall of 1928 Father Wagner began the Lourdes Grotto again, this time using mortar. From the Lourdes shrine, Wagner and his helpers went on to build an assembly of shrines and grottos representing devotional customs and Catholic religiosity, venerating Christ the King, the Sacred Heart, and the Way of the Cross, as well as a large shrine in honor of Our Lady of Fatima, reflecting the expansion of Marian devotion.

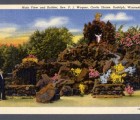

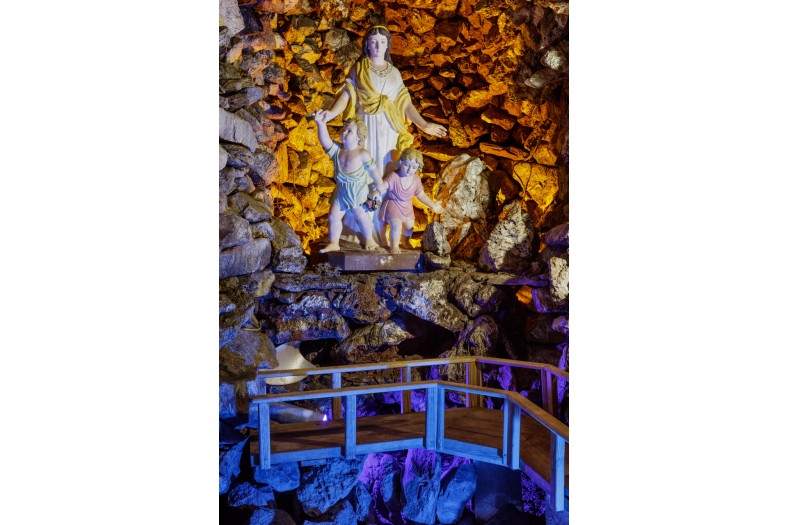

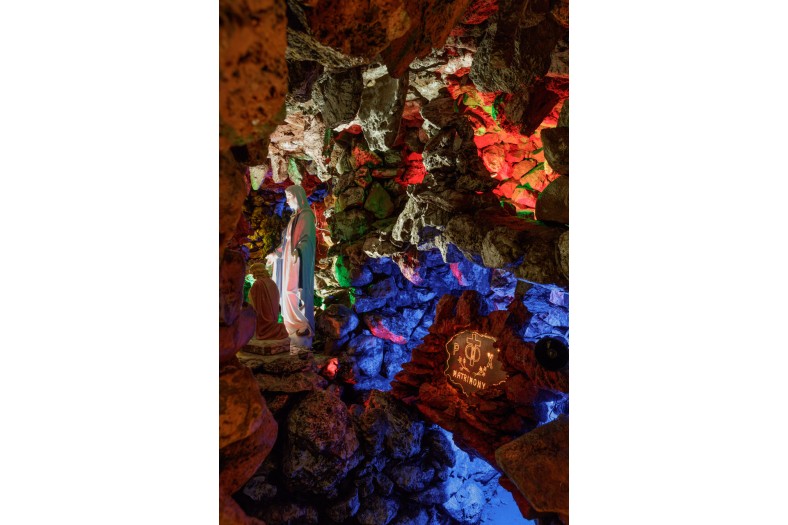

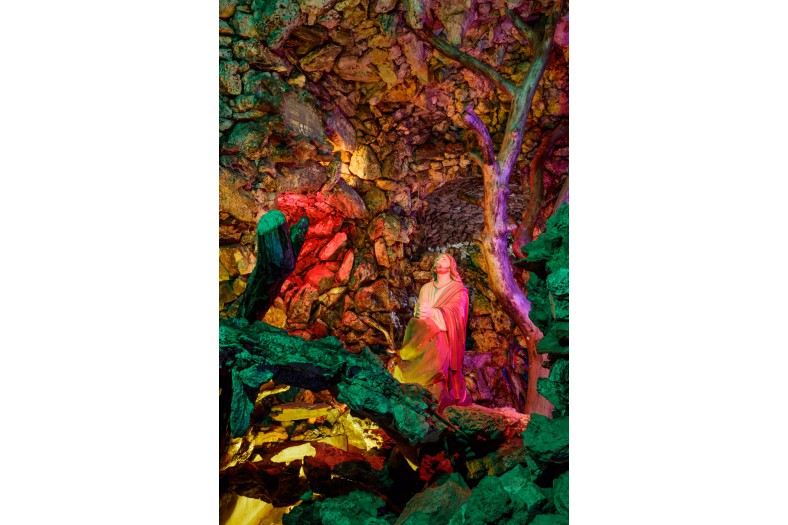

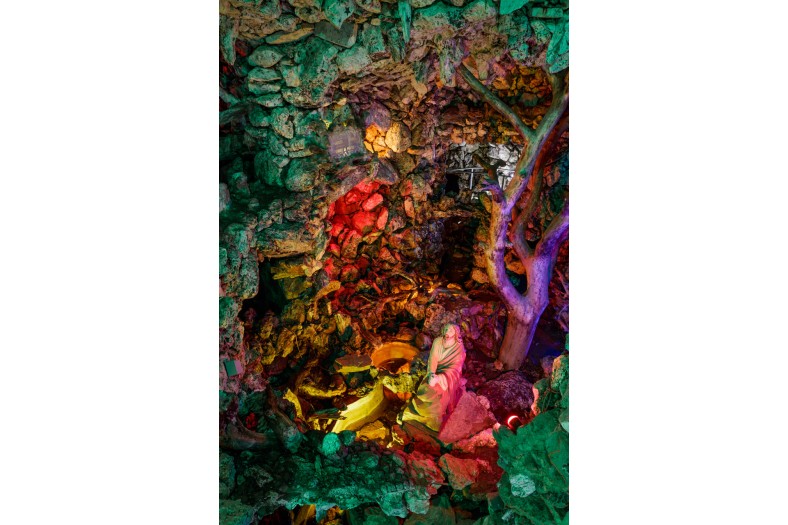

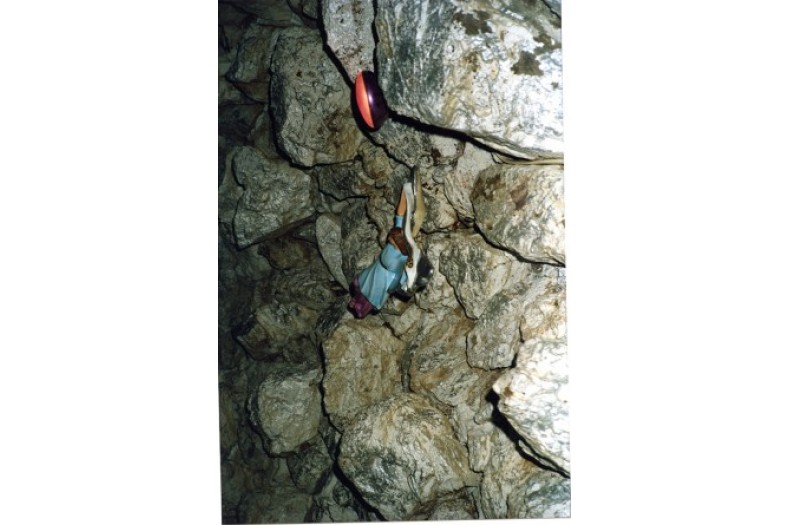

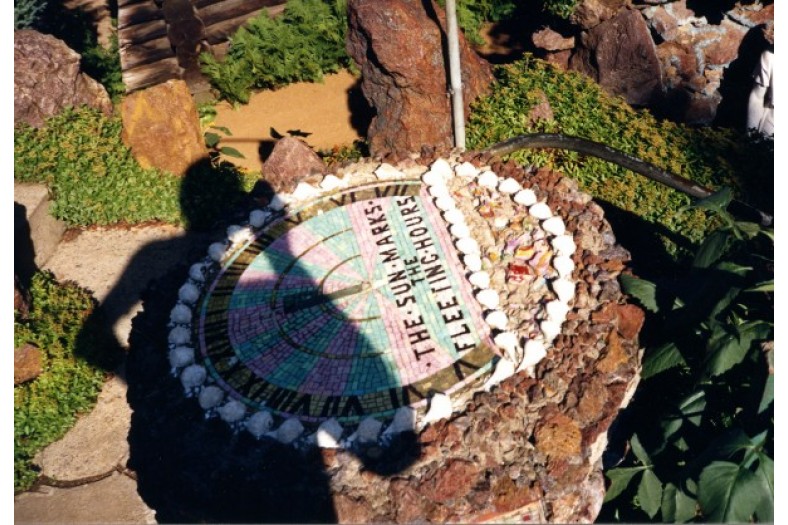

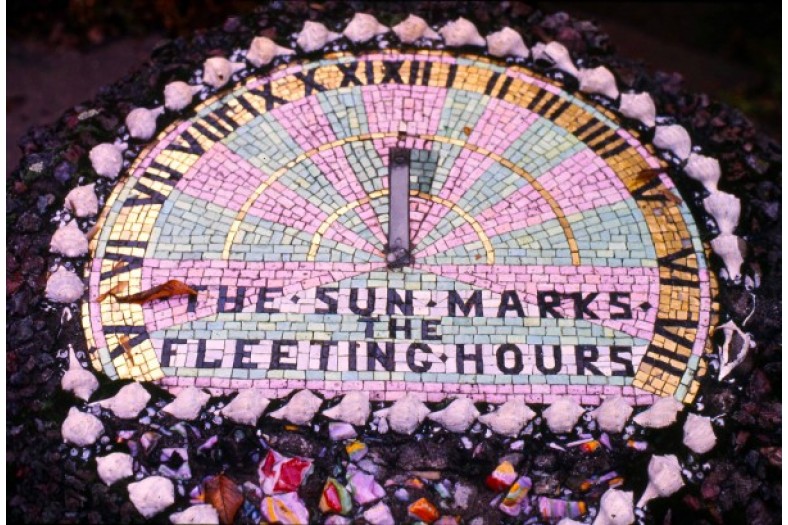

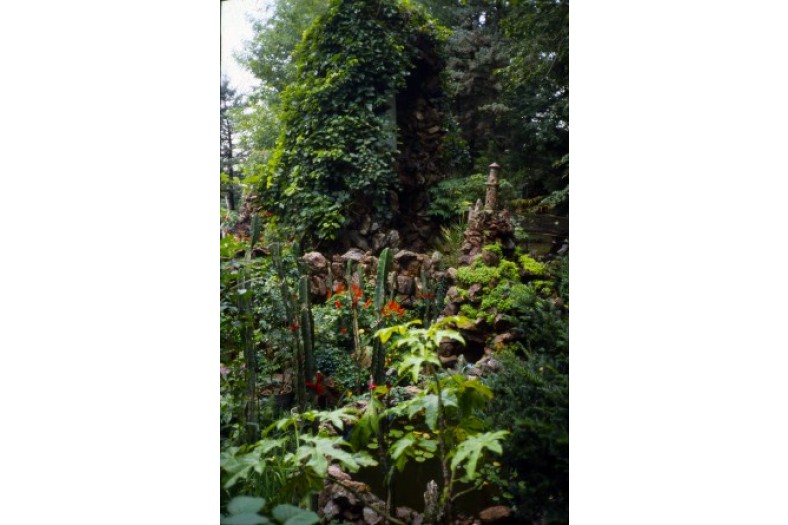

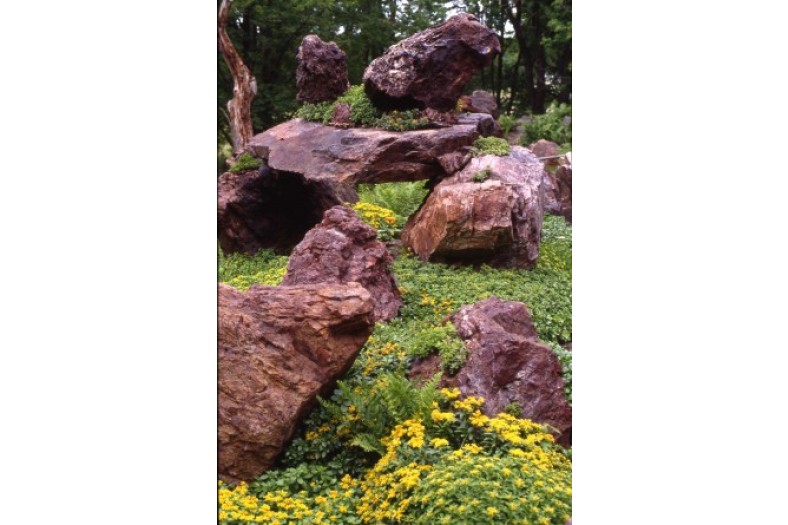

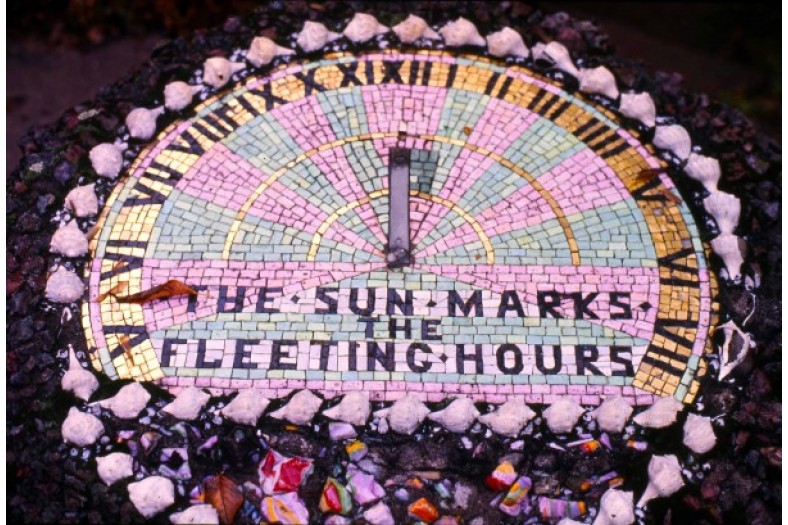

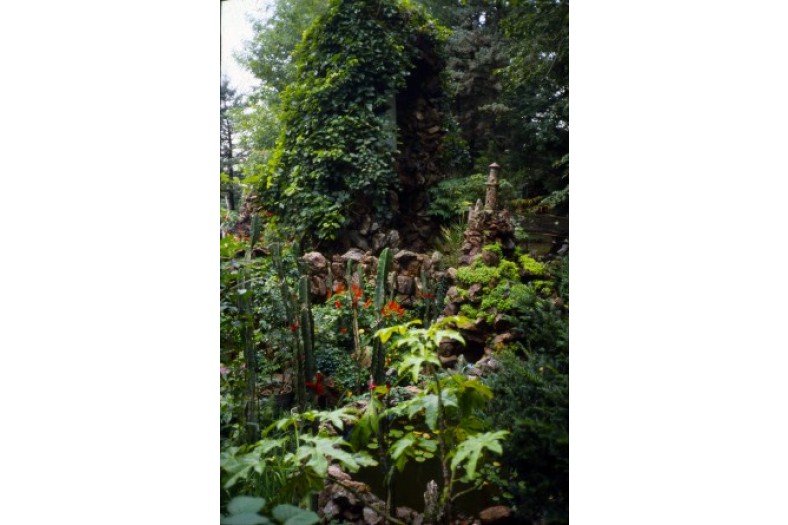

In 1935 Wagner and Rybicki began work on the Garden of Olives. For this theme one might have expected a simple, outdoor grotto. Wagner envisioned a sheltered, interior space, but a plan for the structure was never drawn up. The two began in the center, working entirely intuitively; twenty years later, they had completed a grand grotto, known as the Wonder Cave. The exterior is a monumental, organic mountain-form of local gossan rock, richly planted with flowers, ground cover, and vines. The cave is situated within the grotto-scape of sheltering trees and other grotto and bridge forms, creating a contiguous environment of native minerals and growing things. The grotto interior ingeniously replicates the sensation of a natural cave. Moisture seeps from rocky walls in a labyrinthine passage that winds for one-fifth of a mile on continually changing levels. Although the feeling of being underground is completely convincing, the entire Wonder Cave is above ground level. The passageway leads through an amorphous interior, revealing dimly-lit biblical scenes and an array of symbols, proverbs, devotional images, and references to Christian virtues. The didactic atmosphere is underscored at nearly every turn by tin plaques punctured with tiny holes that outline words and images, lit from the rear with colored lights. Emerging into daylight, the pathway continues to meander up and around the top of the grotto and back down to the ground.

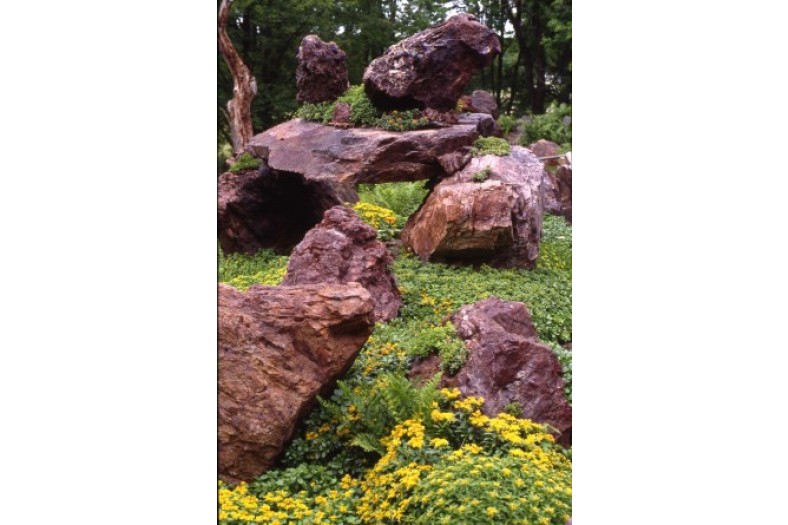

The building program at the Rudolph Grotto was not distinguished by artificial or exotic embellishment, which had come to characterize the Midwestern grottos of Fathers Dobberstein and Wernerus. The two European immigrant priests had adopted a visual language of opulence, achieved through an accretion of unusual materials. In contrast, Father Wagner possessed an uncanny reverence for indigenous, organic materials, which he employed to an opulent end in luxuriant plantings and other manipulations of nature.

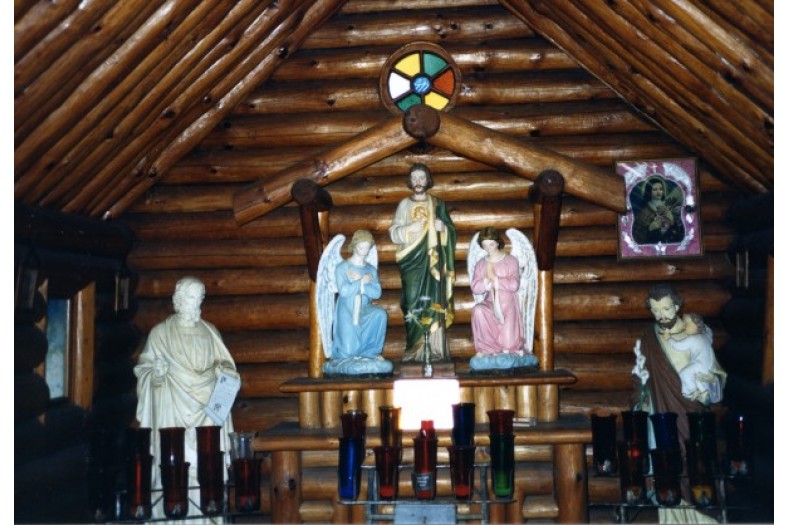

During the winter of 1934, Rybicki and his logging crew cut and prepared enough Norway pine to build a log-cabin gift store and a little log house, called “Wisconsin in Miniature,” inside of which an assortment of tiny scenes relating to the state could be viewed. To provide for various parish social events, a rustic, sprawling complex of picnic tables and shelters was constructed of pine logs, enhanced by a number of grotto-style barbecue grills made of rock.

As with other grottos in the region, the rearrangement of nature in the creation of the Rudolph Grotto entailed legendary feats of physical toil. In 1953, for example, Wagner and Rybicki were told about an interesting rock protruding from a farmer’s field three miles north of Rudolph. Excavating the rock was no small task; the rock seemed to grow larger as the crew dug around it. When finally exposed, they found a massive, seventy-five-ton boulder. Of course, there was no question but that it should be incorporated into the grotto. With characteristic perseverance (and equipment that they fabricated or borrowed), the rock was moved, a quarter-inch at a time, to the Grotto Gardens. Placed on a mound of smaller gossan rocks, the boulder became a focal point in the Patriotism Shrine.

In 1949, the Bishop of La Crosse ordered Wagner to stop work on the Grotto. The bishop was indignant that a real church had not yet been built for the parish, “while the most elaborate developments are going on in this series of caves which to me are perfectly nonsensical....” In response, Father Wagner proved that the Grotto Gardens had been accomplished with his own labor and at no cost to his parish. Nevertheless, he built a conventional church the following year, and his parishioners were able to move out of the school basement.

Father Wagner died on November 1, 1959. Edmund Rybicki continued to care for the grotto, cemetery, and school until his own death in 1991. Local parishioners, under the direction of caretaker Kris Willfahrt, now lovingly care for the Grotto and gardens, including the planting of over thirty-five truckloads of flowers (many of which are donated by local greenhouses) each year. The Rudolph Grotto continues to host an annual Church Picnic on the first Sunday of August.

~Lisa Stone and Jim Zanzi

Contributors

Materials

Rock, mortar, tile

SPACES Archives Holdings

1 folder: clippings, pamphlets, images

Related Documents

Map & Site Information

6975 Grotto Avenue

Rudolph, Wisconsin, 54475

us

Latitude/Longitude: 44.4990981 / -89.8006275

Nearby Environments

Can you provide SPACES with images of this art environment?

Please get in touch!

Rocks for Fun Cafe

Tigerton, Wisconsin

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.