Earlier this year, Annalise Flynn at SPACES connected with Jenenne Whitfield, President and CEO of The Heidelberg Project in Detroit, Michigan, for an update on the acclaimed art environment created by Tyree Guyton. Many thanks to Jenenne for providing this in-depth interview, and we wish her the very best as she transitions into her exciting new role as Director of the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, this month!

The Heidelberg Project, Ted Degener

How are things going at Heidelberg? What are you working on?

Where we are right now with the Heidelberg Project is extremely exciting. Thirty-six years we’re going into, effective April 2022. The way we have started to talk about The Heidelberg Project now is we’ve defined it in terms of eras. The eras are defined by the demolitions and the fires and things like that, so we are in our fourth era. I think what’s most exciting is after 35 years, The Heidelberg Project has finally been accepted in its own city, evidenced by the City of Detroit acknowledging Tyree and The Heidelberg Project with a lifetime achievement award. That was hard fought… Tyree has done as much of the transition of The Heidelberg Project that he’s intending to do. He says there’s always going to be some aspect of The Heidelberg Project there so that it’s never bare. It’s always changing and transitioning, and at the same time, we’re opening the door for other artists to be a part of what we're doing.

What did “dismantling” mean for Tyree? When I talked to Tyree about it last summer [2021], it was clear that it wasn’t abrupt and the site wasn’t going away. Can you talk more about what that meant?

I love the way Tyree described the dismantling process, and he did this from the very beginning. He says, “It took me 35 years to create The Heidelberg Project, taking it down also became a work of art.” How so? In that, as he is carefully dismantling aspects of the project, it’s like coming down 35 floors on an elevator; he has to stop on every floor. It’s a very thoughtful process. It’s a very careful process. And in that way, it becomes a work of art in itself. So that has been really dynamic to watch. As an example, one of the pieces that came off the site is currently on exhibition in New York at the corner of Canal and Elizabeth Street, and this is what we want. These works are his story. They have been around for a long time, so the same care goes into taking these installations apart as was put in when he put them up.

How has the site changed throughout this process? What might people experience that’s different now to how it was before?

I can hardly keep up because it’s such an evolution. So what you’re going to see on Heidelberg Street are what we call those consistent anchor works of art… for example, the charred car hoods, Noah's Ark has been there for over 30 years, the Information Booth (which has gone through many iterations starting with kids who are now in their 30s, if you can believe that), the Pink Hummer and, of course, the Dotty Wotty House and the Number House. These are what we call anchor installations that you can still go and see, but what’s changed is certain works that have been on exhibition you may no longer see or see another variation. What you won't see anymore are works that have become highly valued. Most of the things that have Tyree Guyton faces on it had to be removed because we started to experience some theft, especially when he said he would begin dismantling. The trees and things like that are still intact, of course. Now we've got rotating exhibitions for rotating works of art. What’s really prevalent right now are all the TV screens that are talking about world news and what’s happening. So that’s actually an addition to the project that speaks to the time as a way to keep it alive as certain more prominent works are being removed.

The Heidelberg Project, Courtesy of HP Archives.

What do you hope the expanded artist-in-residence program looks like in terms of the future of Heidelberg? Will Heidelberg become a more collaborative piece?

So we have two: emerging artists and site artists, and both fall under the umbrella of artist-in-residence. The way it unfolds is that the artist meets Tyree, and there’s a conversation. Then there’s a showing of their work to us, and then we talk about the possibility of what they see and how they might want to contribute. Then we listen to that, and if it works in that space like Nawillie – she first came two years ago. She was sitting in a chair with numbers that had her birthday, and she felt like, oh my god, this is a sign. So what she wanted to contribute was to find a way to embrace the trees that had been damaged by the fire. Two years later, she’s here. What we thought would be maybe a six week residency has turned into a year-long residency. It’s an evolution of how that unfolds and how that works. It doesn't always have to work like that, but I’m trying to explain how we embrace the spontaneity and the natural evolution of Heidelberg as we also try to incorporate it into a thoughtful program so we don’t stifle it. How does what you contribute make the site more enriching, and how do you then interact with the community in which you are now helping to impact? It’s been difficult to try to develop this into a program.

Another shorter term residence: a man lost his job during Covid, and he just came here because Heidelberg spoke to him. He was one of the artists that didn’t have a place to sit, but he had a craft where he’s a furniture maker. So he began to take the charred wood from Heidelberg, and he created benches! And we developed it into a fundraiser called Have a Seat. It served a purpose for him because that was a paid residency, and it served a purpose for The Heidelberg Project, and it got him back into making furniture. That is powerful. That is the way we are developing the site residency. When it comes to showing work on the inside, what’s different is we’re now inviting guest curators to curate an exhibition or a show within our space and taking it off of us and stretching the program out so we can have curators' voices be a part of what we’re doing now. So those are the ways in which the artists are working with Heidelberg. It’s more spontaneous on the site, and a little bit more developed and programmed from the inside, based on the curator’s vision.

That makes perfect sense – this intersection of programmatic stability and serendipity, allowing these connections to manifest in a natural way that serves Heidelberg and the artist and the community.

What I’ve tried to ask foundations to embrace is the uncertainty. Let’s think about the times we’re living in now, to embrace the uncertainty of how art is often created. It’s created out of situations and circumstances. We’ve got to embrace that part of things and not always look to stage and program every single thing that happens. Leave room for spontaneity and, in that way, it becomes this natural evolution. That is how it stays relevant, and that is how it’s adapted to the times we’re living in.

It sounds like it’s been working so far.

Well, it works for us! We learned to get out of the way of Heidelberg a long time ago. It’s the truth, honestly.

How has the community around The Heidelberg Project changed over the years?

Everything is complicated. When we started, 48027 was one of the worst zip codes in Detroit. 75% of the community lived below the poverty level. The African American male mortality rate was insane. Young men between 14 and 28 only had a 45% chance of escaping death or jail. Those were the statistics when Tyree started and up to 2010. 2008 is when Detroit started becoming really public nationally and internationally and started to be this “come back” city. Everyone is looking for cheap property, and of course, Heidelberg was doing its thing a long time ago, but it has since attracted other people to the area. When people start looking for places, they want to find cheap real estate, and then if there’s an art initiative going on, oh my god, right? So we have now seen a growth of various people from different areas that have moved into this area. Most of them are artists. There is a mix of races, but most of them are Caucasian, and there has been this fear that the few residents that are here are going to be pushed out. So we’re working within The Heidelberg Project to, number one, have the people that are moving in have a sense of responsibility to this community. How are we doing that? Through a land trust – a unique land trust that we’re trying to work with the city on. That's one thing. The second thing is the city, through the cultural affairs department, has worked on the land bank to put a moratorium on purchasing property in this area without The Heidelberg Project and the community group’s support. And then we’re looking at how we can protect the existing residents so their property values don’t start to soar because we are making this area more attractive. So we’re right there in the grind of trying to really be this community arts organization that is looking at all these different layers and what influence we can have since we are partly responsible for what’s happening in the area. It’s complicated, but we’re right here in the middle of it.

We’re training the next generation to pick up the baton and keep going. We’re helping a community become economically stable where all people can participate. That’s the symbolism behind the dots. So we’re not trying to say – no outsiders can come in. We need that energy, we need that income, but how do you give back? That’s what’s important.

When I was in Detroit [summer 2021], the creative work there totally blew me away. And I know that I only saw really a fraction of what’s happening. Why is so much of this happening in Detroit?

It’s not just coming from me, but others have said that Tyree is the kind of godfather of the arts resurgence in Detroit that started in 1986. Even the techno musicians, the big boys – Carl Craig, Juan Atkins – some of these guys who are well known were 17, 16 years old sitting on the curb creating their beats while he [Tyree] was painting. We look at kids who came to see the project, they’re coming to us now, [saying] “I was 10 years old when my dad first brought me here, and now I’m 40 and I’m an artist.” It’s crazy. It’s hard to believe. And the fight – I think Tyree really demonstrated the power of art and creativity in a community, and he inspired others. One of my favorite stories is the gentleman who has a really well known restaurant in Detroit called Slows Bar BQ. Everyone and their mother would go to Slows when they came here. This was a young kid from Germany who saw Heidelberg, met Tyree, and said – well, if he can do this, what can I do? And he came back to Detroit because of Heidelberg to create a small business which then became known around the country. There's so many stories like that. His [Tyree’s] fight and the demolitions really taught artists in Detroit – if you want this, you can do it, but you’ve really got to stand for something. And that became a form of inspiration.

Even [Olayami] Dabls talks about how Tyree was a forerunner even though he’s older than Tyree. He gave a lot of people courage to pursue. We have no idea how wide a net we’ve cast at this point.

Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum, 2021. Photo by Annalise Flynn.

Spectra-Gate, 2021. Photo by Annalise Flynn.

You two are close with Dr. Charles Smith and talk to him quite a bit. I’m wondering what that network between artists looks like? With Dr. Smith, with other artists who are connected in Detroit? It was so interesting and so fun that I had just driven by and seen this installation [Spectra-Gate], and I showed it to Tyree and he said “Oh, that’s Matt [Corbin]. He was my teacher.” I’m really interested in those interpersonal connections.

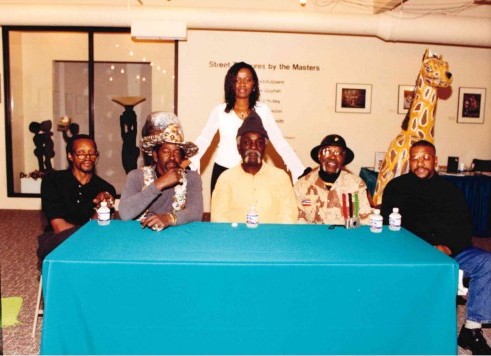

I have a vision right now of when I curated my first exhibition in 2001. It was Tyree Guyton, John Abdul, Dr. Charles Smith, Lonnie Holley, and Mr. Imagination. To see these guys walking down Heidelberg Street in a line, coming at me as I was taking a picture, and the way they just loved on each other. That’s the only way I can put it. Those really powerful, great artists are not jealous of each other. They actually love on each other. Dr. Smith is a fine example of that. I don’t often see it in the trained artists as I see it in those who aren’t really trained but they're doing something intuitively. Tyree blurs the lines because he’s a trained artist, but he says he wanted to forget everything he learned in art school in exchange for the creativity that comes from the soul. So I think what you’re really seeing – that camaraderie is a connection with these artists from the soul. That’s what I see.

L to R: Lonnie Holley, Gregory Warmack (Mr. Imagination), Jenenne Whitfield, John Abdul, Dr. Charles Smith, and Tyree Guyton

The African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive by Dr. Charles Smith. Photo by David Kargl.

For you and Tyree, what are your hopes for the future of the site?

Well, we built something and not just the physicality of it, but the whole idea, I guess, of what Heidelberg represents. And the important thing is a quote that I’ve used when I’ve written – it’s not so much about us preserving things, as much as we’re preserving the human spirit and trying to teach and instill the idea that the power truly is in the people. Who is it, Margaret Mead, that said this quote? “Never doubt that a small group of citizens or one citizen can change the world. Indeed it’s the only thing that ever has.” And I love that because change is possible but so often we put our hope in, for example, government. And basically, Heidelberg was established guerilla style, and Tyree basically said fuck the government, the government has not done shit for the people. I’m going to do something. I don’t have any money, but let me see what I can do. And look what he’s done. If that’s not a reflection of the power being in the people, I don’t know what is. So I think the legacy of us is being able to pass along the principles and the work and the evolution. Heidelberg is a living museum. It’s not a museum for the dead. And not get so bent on preserving things as much as we’re preserving the human spirit. That’s what it’s really about.

Tell us about your new role at AVAM! What are you excited about? How will this impact your work at Heidelberg?

I am very excited to meet and work with a great staff of people who are dedicated to AVAM and have thoughts and ideas on new possibilities. I am also excited to learn about Baltimore's landscape and its dynamic arts scene.

Many thanks to Jenenne Whitfield for providing this detailed update on The Heidelberg Project. SPACES wishes her the best of luck in her exciting new role, and we look forward to seeing what she does at the American Visionary Art Museum!

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.