Born in Alabama in 1917, Noah Purifoy lived and worked most of his life in Los Angeles and Joshua Tree, California, where he died in 2004. After 11 years of public policy work for the California Arts Council, Purifoy moved his practice out to the Mojave desert. For the last 15 years of his life, he was dedicated to creating large-scale sculptures on the desert floor. Constructed entirely from junked materials, this otherworldly environment is one of California’s great art historical wonders.

Joe Lewis is an artist, writer, educator, and the president of the Noah Purifoy Foundation who met Noah after seeing and writing about his retrospective at the California African American Museum in 1997. This year, Lewis took the time to meet with SPACES Archives and share about the Foundation and how they're continuing to use the "spirit of Noah" as their guiding philosophy.

Urban Arts Initiative (UAI) day at the Outdoor Museum. Pictured are Joe Lewis and Maria Myrick greeting the students. NPF thanks the Ruth Foundation for the Arts for generously supporting this much needed program.

Annalise Flynn

I'd love to hear how you became involved with the Noah Purifoy Foundation and how you guys do your work. I know you're a really small team. I'm so fascinated to hear how you manage all of these different projects.

Joe Lewis

Yeah, we're all volunteers. It's a labor of love. My name is Joe Lewis, and I am the president of the Noah Purifoy Foundation. I've been the president since 2000. I'm a non-media-specific, post-studio artist, which means I never had a studio, and I had to make everything à la minute on site, wherever it was. I am a professor at the University of California, Irvine, and I've been there for 13 years. I've been an administrator and a writer for 30 years. I was the dean at FIT in New York and co-founder of Fashion Moda in the South Bronx in the 70s, which was an alternative space that was founded on the idea that no one particular group had a stranglehold on the development and implementation of aesthetic criteria. The downtown art scene had a handful of galleries, and there were only a handful of museums, and they weren't showing a diverse group of people – women, people of color in particular. And Fashion Moda was a place that brought all those folks together from the South Bronx, from Europe, from Asia, from the South, from the West of the United States to work in the creative process, which is really interesting because Noah was very interested in the creative process, and so was I 20 years prior to that, but in a different way. Noah was looking at it from a kind of a manual, one-on-one relationship with the creative process. I was looking at it from a community point of view, although Noah also worked in community activities.

Noah had a retrospective at the California African American Museum, I think it was ‘97. And my phone was, like, jumping off the hook – [people] saying, Joe, you gotta go see this show. And I saw the show, and I was like – What? It blew my mind. I was like, transfixed. It was a transformative experience as an artist to see Noah's work. They had pulled a lot of pieces out of the desert, and they had more discrete work. It just so happened that that day Noah spoke, and I went and heard him speak. And at that time, I was looking at Motherwell, I was looking for a model for being an artist, scholar, artist activator. I was looking at Smithson kind of creating a field. And I hadn't found any person of color who had this multifaceted relationship with the arts and, you know, was a founding member of the California Arts Council, authored their first program with artists and prisons, artists and schools, artists communities, the Watts Towers Arts Center. I heard him speak, and I was just like, Wow. This changed everything for me, literally.

I did not go and introduce myself to him, but I did go home and I called Art in America and said, Hey, I want to write a review about this show. Fast forward maybe a year and a half or so, I got invited to a luncheon, and I was walking around and some woman came over to me, looked at my name tag, and said, “You wouldn't happen to be the Joe Lewis who wrote that review of Noah's show in Art in America, would you?” And I said, Yeah, that was me. She literally took me by the ear, I'm serious, and dragged me over to the table and plopped me down next to Noah. And we started talking, and he said that was the first article that he thought told his story.

Shortly thereafter, I went out to the desert to visit him, and I got him the Distinguished Artist interview at the College Art Association in ‘99. Soon after, Richard Candida Smith, the president of the Noah Purifoy Foundation, retired. And then Sue, a co-founder of the Foundation and the woman who dragged me over to Noah, asked me to be president. And I said, Yeah, sure – not knowing what was in store for me over the years.

We [the board] were trying to elevate Noah's profile internationally and nationally, and that happened in 2015 with the retrospective at LACMA [Junk Dada] which really blew everybody's mind. People sort of said – What? Who is this guy? That show really put Noah on the map. The floodgates opened for people visiting the site [the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Art], although people from all over the world had visited that site for years.

Initial meeting with UCLA/Getty conservators and NPF board members. NPF thanks the Mellon Foundation for their generous support of their conservation efforts.

Annalise

I heard you guys recently received a grant from the Ruth Foundation for the Arts, which is awesome.

Joe

We have three years funding now for our Urban Arts Initiative, where we bring in students from Title I middle schools in South Central LA out to the site. We have teaching artists that go in with curriculum before the trip, and then after the trip, they make things kind of in relation to what they saw. We give them a healthy lunch. They go out on a party bus. We run videos of Noah's interviews on the party bus, a straight up party bus. [laughing] Not a school bus. They do a windshield tour of Joshua Tree National Park led by one of the park rangers.

I just got four requests [from schools], Are you doing it again this year? I said we had to stop because we ran out of money, but now we have three years, definitely – possibly four. And Ruth Arts was really important for that. So it's been fantastic for us. And they'll keep that program going. Everyone loves that program. Even the parents want to come. You know, a lot of those kids have never been out of their neighborhood.

UCLA conservation students touring the Museum

Annalise

I was really excited to hear about the support for that program. It sounds so lovely, so congrats.

Joe

And secondly, we just got a $500,000 Mellon Foundation grant for conservation and preservation of the site. We're partnering with the Getty and the UCLA conservation program that is created to attract BIPOC students into the field of conservation and preservation. So we're building a little laboratory on site, and also, with that laboratory, we'll be able to work with the local Indigenous tribes for their conservation projects as well and also offer training for them. So that's a huge project. And we'll do a condition report for every piece on site, and then we'll put together a plan for conservation and preservation. We've been doing it for years in an ad hoc way, but now we have professional folks that we'll be working with, so that's very exciting for us, and it will definitely keep the place going in a more detailed way.

UCLA conservation students assessing work in the Quonset Hut

NPF crew repairing Weathervane with support from Mellon Foundation

Annalise

I have a question about the early days of the Foundation. A lot of times with sites like this, the artist passes away, and then people scramble. They come together and they're like – What do we do? And I know that the Noah Purifoy Foundation was actually formed several years before Noah died. So I'm curious – what was that partnership like? What kinds of wishes did Noah express? What sort of directives did he give? What were his hopes for the work of the Foundation?

Joe

No fences.

That's pretty much it. And he thought we were nuts. Like, You want to save this stuff? Are you kidding me? He was not really on board with it, even though he was kind of initially right. But what happened was some county inspector came to the site and said, This is a pile of junk, it's an eyesore, it's dangerous, blah, blah, blah, I'm going to bulldoze this. And we went like, What? So we rounded up the troops. We got a meeting with the commissioner of the county. We said, This is not some crazy guy in the desert. This is a very well known, respected artist. What can we do to assuage these issues? And what happened was we got a meeting with 12, maybe 14, inspectors – everybody from vector control, waste management, etc. We met at the site, walked the site, got a list of, like, 30 things we needed to do and did those 30 things. And when we did that, Noah realized that we were serious. But, yeah, his only request was no fence.

Annalise

Well, I am extremely not surprised to hear that. I was in Detroit two summers ago, and I went to visit Tyree Guyton at Heidelberg and Olayami Dabls at the African Bead Museum. And both of them, unprompted, immediately brought up how important it was to them to not have fences and the whole philosophy behind that, creating a sense of community trust. And it was just very interesting to me – that they both had such similar things to say. And now to hear that Noah thought that as well. It makes a lot of sense to me.

Joe

Heidelberg is, as I'm sure you know, it started off as some little thing. It didn't really kind of have any structure from what I remember. And now they've come together to really do something much more substantial in terms of organization. I think that's really great. I mean, it's a great site and has a lot of resonance with what we feel about Noah's work and Noah's site.

Annalise

Yeah, it's stunning, Detroit. There's just so much stuff going on there that's so great. Just like in Joshua Tree in the desert out there. There's so many wonderful things happening. Another question for you – so I know that Noah along with Judson Powell was also the inaugural director out of the Watts Towers Art Center. Did he ever talk about the Towers and any sort of influence that Simon's work had on his own?

Joe

No, not with me. He never mentioned the Towers. And I think when he moved out to the desert, he pretty much cut ties with L.A. And it was kind of like he was looking for a place. When he retired – he retired. And there is some controversy around what I'm about to say, but Noah was broke. He couldn't afford to live in L.A. He had a small pension. That was it. He had to leave L.A. Some people say, Well, no, he got invited, blah, blah. No. It was fortunate that Debbie Brewer said, Hey, come live in my son's trailer. He was looking for a place to do these ideas. He did have these ideas already, but his ability to actually do that was seriously hampered by his financial situation. So it was really fortuitous that Debbie, who was one of the artists in 66 Signs of Neon, invited him to come out and live in her son's trailer. So he had the idea that he wanted to make this stuff. He was just looking to figure out a way to do that.

Annalise

You mentioned that the Foundation is developing a conservation strategy for the site via support from a Mellon grant. And so I'm just curious, and maybe this is sort of an ongoing question, but what is the philosophy of preservation when it comes to the pieces out there? I know you have the sign up on Earth Piece (see below) about it being reclaimed by the desert, and the conditions are really harsh, and you're really fighting the elements out there. So what's the thought process behind that?

Joe

Noah considered the environment his collaborator, so he was collaborating with that desert environment, whatever the pieces were. Our philosophy is in the spirit of Noah. That's what it's been like for the past 20 years. If something needs to be painted red, we paint it red. We don't change the formation of any of the work. We have really good documentation of all the pieces.

Maybe this story will help you understand our philosophy. We get a call from the Corcoran Museum. It's a curator who says, Oh, you know, this strap fell off of this piece. What should we do? And I said, Go buy another strap. And you could hear this audible gasp on the other end. I can only imagine. [laughing] So we want to stay true to Noah's work. But the other thing is that Noah, he was a Seabee. He was an engineer in a sense. He built airfields and quonset huts during the second World War in the South Pacific. He taught industrial arts in high school.

So just like Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, they wanted to pull it down. When they got out there, they figured out they really couldn't pull it down because it was so well built. The only reason why a lot of that stuff is still on the desert floor is because it's really well built. We won't change anything that Noah did, but we will definitely work within the parameters that he did with the same materials, et cetera. Now, that's not the academic conservation/ preservation point of view or perspective. However, I think that perspective is changing, especially when dealing with someone like Noah and the kind of work that he does. So, for example, from The Point of View of the Little People, we've changed those clothes in the past 20 years, 100 times, 30, 40, 50 times. It's in the spirit of what Noah would do. He didn't have this precious concept of the work. It wasn't precious. If he needed to put in another joist or something, he just put it in. That's how it works. So it's going to be interesting working with the conservators, kind of melding our ideas together, which is good. I think having a condition report for all the pieces is perfect for us. Having a full on workshop where we can actually work in a more scientific way is great. It will extend the life of a lot of the work there.

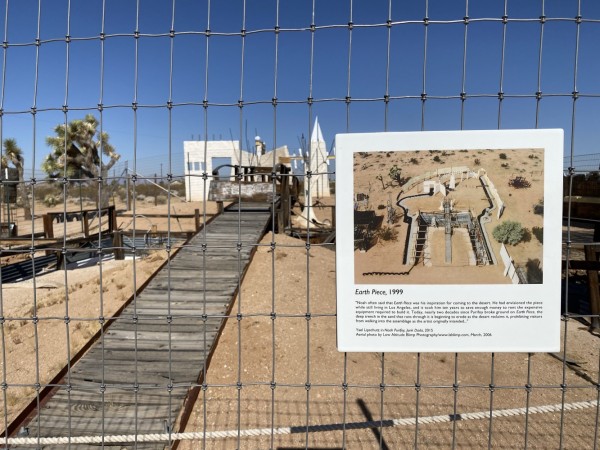

"Noah often said that Earth Piece was his inspiration for coming to the desert. He had envisioned the piece while still living in Los Angeles, and it took him ten years to save enough money to rent the expensive equipment required to build it. Today, nearly two decades since Purifoy broke ground on Earth Piece, the deep trench in the sand that runs through it is beginning to erode as the desert reclaims it, prohibiting visitors from walking into the assemblage as the artist originally intended..." Yael Lipschutz in Noah Purifoy, Junk Dada, 2015.

The Point of View of Little People. Annalise Flynn, 2023.

Annalise

When is this set to start happening?

Joe

It's happening. We've been meeting since the beginning of the year. They've been out to the site, the conservators, a couple of times. We're building the workshop now, so we're kind of in the process of doing all the permitting and et cetera.

Annalise

Wow. I think this is just such important information to collect and hold on to. To, I think, share potentially with other sites who are going through a similar process or who will inevitably go through a similar process in the future.

My final question is – what’s on the horizon? It sounds like there's so much exciting stuff coming up for y’all. What is the potential length of this conservation project?

Joe

Well, it's funded for three years. So I guess we will review after about a year and a half and see where we're at, if we need to continue to seek funding for that, or how that's actually going to play out. But we will have established this workspace, and maybe we'll partner with the Getty and UCLA to have that as a field operations site. That's kind of what we might be thinking about.

They can work in particular with the local tribes. One of the conservators on the team has done work with a couple of the tribes in the locale, so we're going to be offering that and tools that people can borrow and use.

Annalise

Well, I would love to hear more about this. I will make sure I'm up on what's happening on the website and whatnot, and maybe I'll bother you about it at some point in the future. But this is so exciting.

Joe

It is exciting. You got to remember, when we started out, we had like 20 grand in the bank given by eight people. That's what we did for years. And when Noah passed, he donated everything to the Foundation. And when one of our trustees Debbie Brewer passed, she gave everything to Noah, the ten acres [in Joshua Tree]. And then some people in their family were very upset about that. So Noah said, Well, let me just have the two and a half acres I've done most of the work on and give the rest of it back to the family. And then over a couple of years we bought those parcels back. So now we have the ten acres, which was the original gift from Debbie Brewer to Noah.

Initial meeting with UCLA/Getty conservators and NPF board members

Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture | Photo: Low Altitude Blimp Photography | www.lablimp.com

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.