AnarchitectRichard Greaves (b. 1952)

Non Extant

Rue Du Limousin, Quebec, Quebec, G1X 1L5, Canada

begun 1989

About the Artist/Site

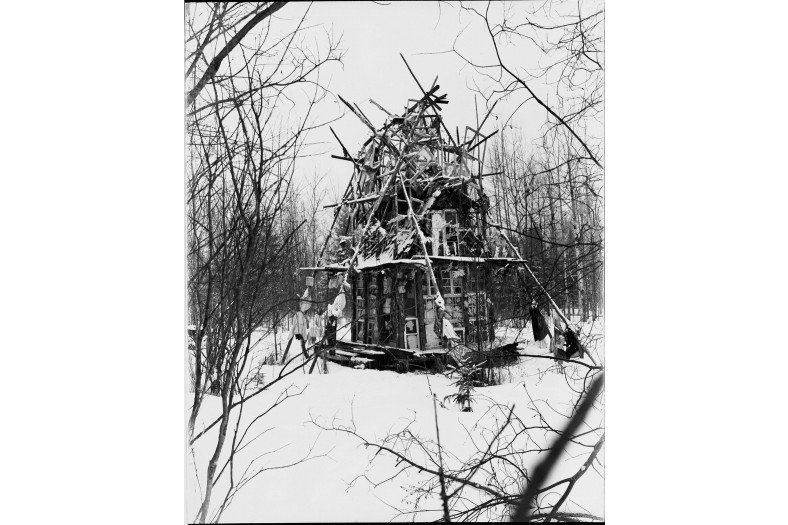

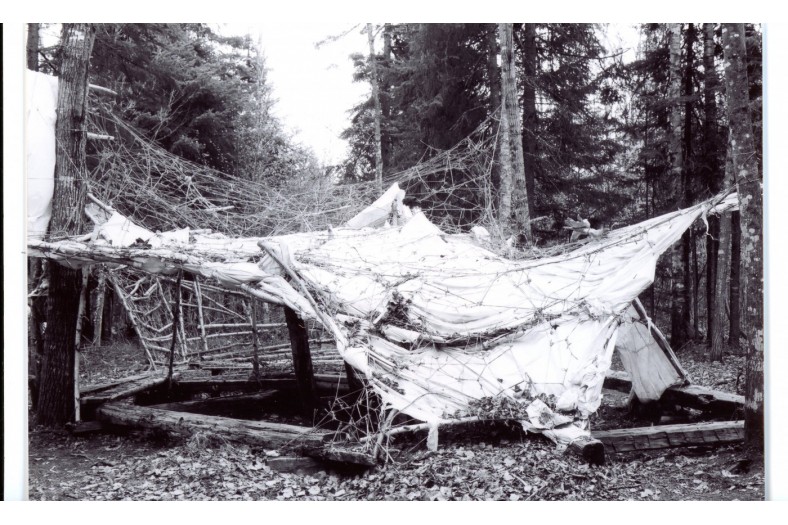

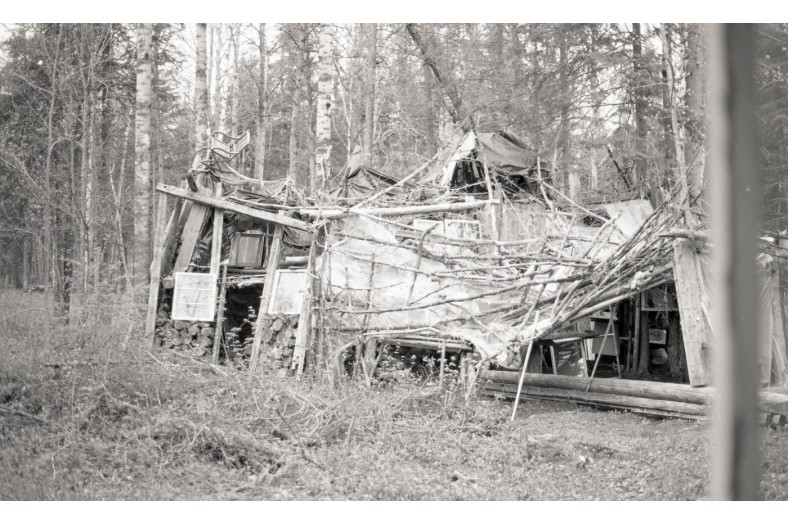

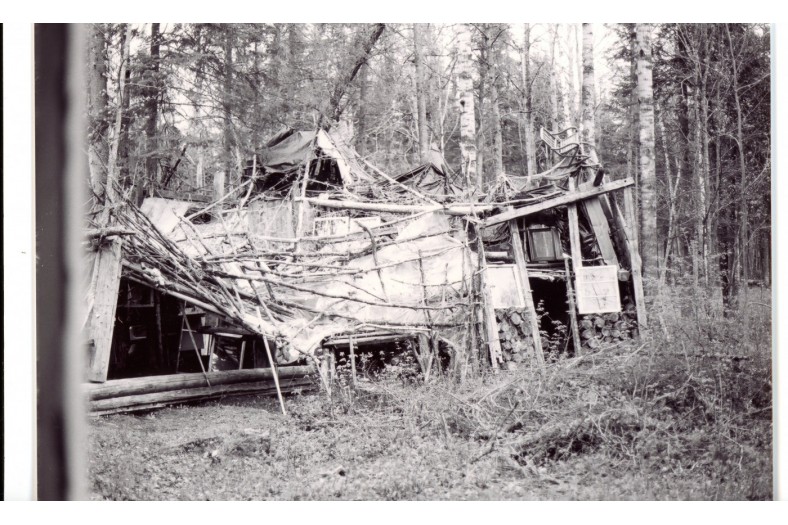

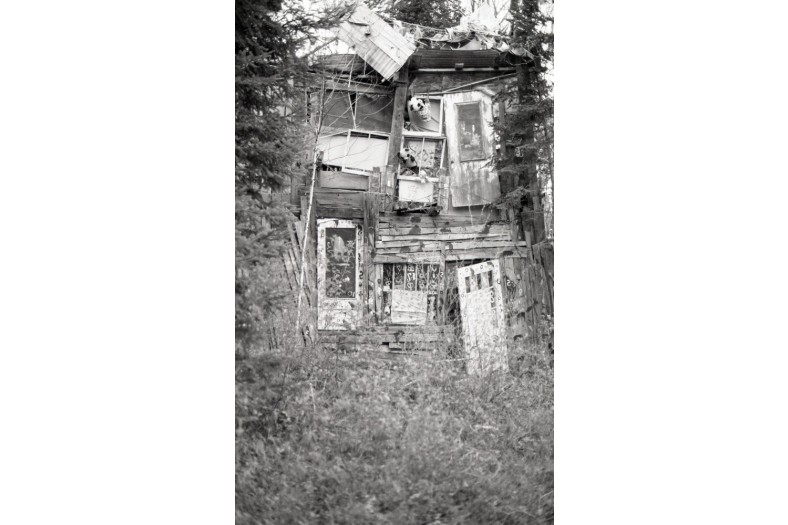

For some time now, we have known that Richard Greaves has turned away from his fabulous fantasy architecture, improvised constructions created from assemblages of lumber and materials collected from the demolition of nearby barns or homes. Beginning in 1989 he had patiently erected a sort of ramshackle village sheltered in the middle of the forest in Québec’s Beauce region: some twenty cabins were constructed without a nail (“in order to not wound the material…”) but instead with reused nylon twine recycled from the local farmers. His grouping of buildings gave the impression of being totally imbalanced and on the point of falling down, thus giving these “anarchitectures” a rather cubist aspect (think: Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau). They had a dreamlike, deformed perspective worthy of the décor of the 1920 expressionist film by Robert Wiene, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Recently I received a notice from the Galerie des Nanas in Québec that related to the disappearance of the site. One of Greaves’ neighbors, upset by the constant presence of visitors who tramped across his land and environs in order to see Greaves’ work, had the very bad idea to pull everything down, assuming that the general indifference of the Canadian art world would mean that no one would care. A pile of boards and a depressing view are all that now remain of this impressive masterpiece of wild and inspired bricolage. Forgetfulness, destruction, complicated inheritance issues, problems with the neighbors…all of these are the great classic problems which regularly put these spontaneous works of art created by self-taught builders in danger. Even if one believes that art brut will ultimately find a dignified place in the cultural field, Greaves’ work won’t have escaped the threat, and it has joined the long list of victims of obscurantism, those opposed to diffusion of knowledge of any kind.

~Jean-Michel Chesné

Translated by Jo Farb Hernández

Richard Greaves [1]

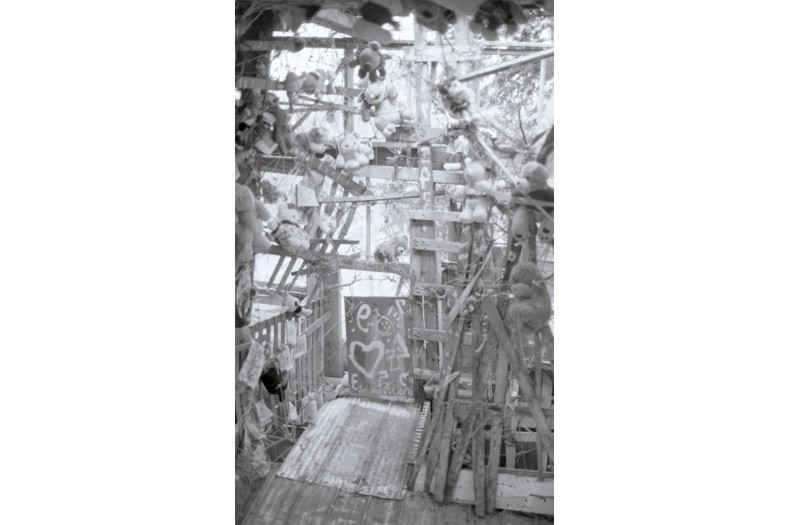

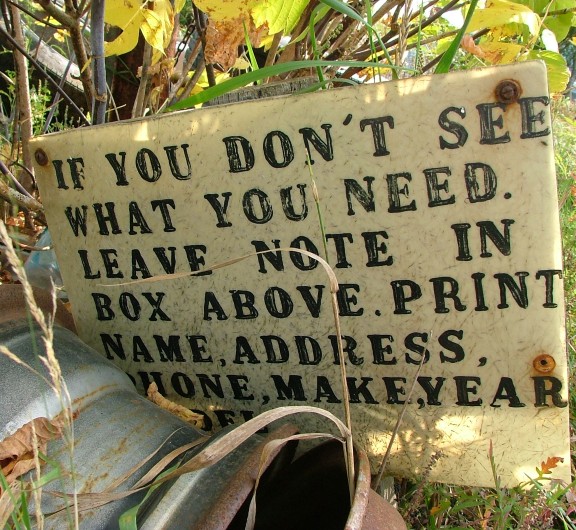

Around 1984, Richard Greaves (b. 1952, Montreal, Québec, Canada) turned his back on the city life of his native Montreal, and moved out to Beauce County. [2] He took up residence on a wild piece of land, located in a remote rural area, that he and some friends had bought eight years before. There, in 1989, he started to display on the ground and in trees installations that he created from objects gleaned from locals and the dumps: computer keyboards and screens, typewriters, clothes, toys, shoes, household appliances, sports equipment, televisions, umbrellas. Beginning one year later, and continuing until 2000, Greaves added twenty buildings and huts to this immense site (250 meters by 1.6 kilometers), dismantling the wood and other components from hundred-year-old abandoned barns and houses, and reinstalling the recycled elements in new configurations.

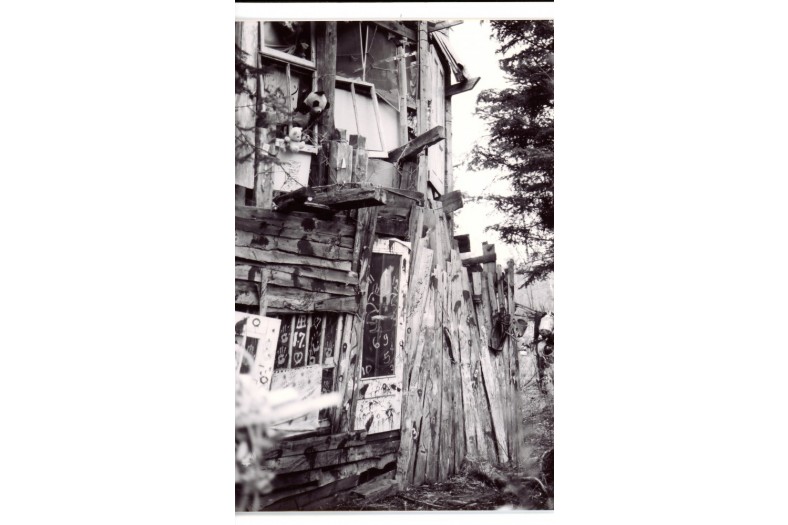

Until he quit his land in 2009, the site constantly expanded as a work-in-progress. Operating at a fast pace, and generally without help, Greaves defined a building process in accordance with his unique set of principles, means and knowledge. Untrained in architecture, he never sketched plans, preferring to confront the practicalities of time and space as they existed in reality. A spiritual and aesthetic cousin to Clarence Schmidt’s House of Mirrors (c. 1940-68), Greaves’ art environment was a masterfully orchestrated chaos in which materials and nature conversed in growing and unpredictable ways. A battlefield effect was sustained by the absence of perpendiculars, giving the impression that the buildings were on the verge of collapse. Greaves took advantage of the qualities of the diagonal and the broken plane. Like houses of cards, these buildings defied the laws of gravity and shattered the standards of conventional constructions. He once said: “My houses aren’t twisted, they are deliberately asymmetrical. They are strong because they have angles that you can’t make with nails… A nail is fixed, it stops the evolution, but a rope is patient, it can contort itself… Rope makes it possible to structure a building without hurting it, without assaulting it… With rope, it’s great because it still moves. Artworks have to continue. I hate things that are too stable.” [3]

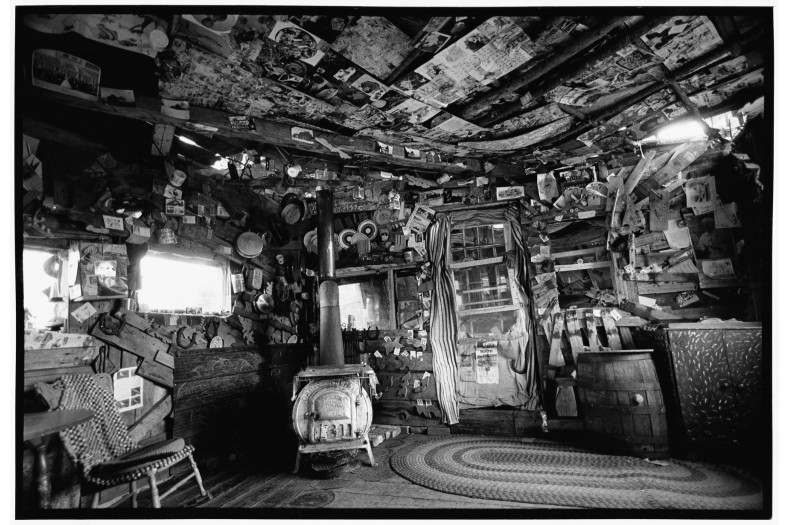

The walls, ceilings and roof of these architectures were covered with various objects. In The Three Little Pigs’ House (8 meters high by 20 meters wide), an entire section was lined with clothing and shoes, which incidentally acted as soundproofing. Another was filled with personal photographs, wood cut out in bird shapes, fragments of mirrors, and pages of books. Window frames were often used as dividers. Most constructions contained chairs, sofas and beds, but all had a wood stove and a toilet—the first incinerating waste (providing heat during harsh winters) and the second evacuating them: “For each building, I start by making the toilet, and then I make the house around it, as if I were already aware of the importance of our remains, our emissions… The building is like my body, and my emissions are there.” [4] Among the many books found in his cabins (Greaves is an avid reader) was Lettres de Van Gogh à son frère Theo (1937), in which he had underlined the following passage: “Art is man added to nature.”

For Greaves, nature always asserts its rights, and he was conscious that his buildings were temporary incursions. His approach combined a belief in the organic growth and the inevitable decline of his constructions. Fueled with a vision that exhibited collective concerns and idealistic ambitions, his convictions about recycling were anchored in ecological awareness for the benefit of future generations.

~Valérie Rousseau

Curator, American Folk Art Museum, New York

[1] This text is adapted from: Valérie Rousseau, “Visionary Architectures,” in Ralph Rugoff (ed.), Alternative Guide to the Universe (London: Hayward Publishing, 2013), and Sarah Lombardi and Valérie Rousseau, “Richard Greaves: Architect of the Possible,” in Lombardi and Rousseau (eds.), Richard Greaves: Anarchitecte/Anarchitect (Montreal/Milan: Société des arts indisciplinés/5 Continents Editions, 2005), with photographs by Mario del Curto, and texts by Roger Cardinal, Jean-Louis Lanoux, Richard Greaves, and Lucienne Peiry.

[2] Greaves studied theology and graphic design. He later worked in the hotel industry.

[3] Richard Greaves, interview with Philippe Lespinasse, 2005. Archives Société des arts indisciplinés, Montréal.

[4] Ibid.

Contributors

Related Documents

Map & Site Information

Rue Du Limousin

Quebec, Quebec, G1X 1L5

ca

Latitude/Longitude: 46.8130816 / -71.2074596

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.