Gabriel Chalfin-Piney is a performance artist and organizer with a background in cohort creation and public programming. They are interested in making by way of olfactory, gustatory, and tactile experiments, prompting audience members to participate as co-creators. Failure, co-learning, and storytelling are central to the projects that they participate in.

God’s Glove, 2022, Speedwell Contemporary Performance by Gabriel Chalfin-Piney metal bells, beeswax candles, broom head, pomegranate, clementines, matches, whistle, matches, milkweed seed pods

Daily Bread, 2019, High Concept Labs at Mana Contemporary Performance with Amanda Bailey and Tamas Vilaghy local boiled beets, red onion, arugula and goat cheese

Can you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your creative practice?

My name is Gabriel Chalfin-Piney, I am a Chicago-based artist and organizer. I work across a number of mediums, most recently working in sculpture and performance. Vernacular art and art environments have deeply inspired me, and the ones I’ve visited often have an immersive theatrical heart to them. The makers seem to consider the public uniquely and offer a multi-sensorial gift to the audience who experiences the site. This observed quality is something that has become a goal of my own practice, considering the audience first, working from presentation then backwards into planning. Working with others gives me consistent life-giving access to joy. I have found having a physically engaged collaborative practice equally as important as my solitary slow-moving personal practice.

This year I am working on two distinct bodies of work with connections to spirituality and Judaism. When Souls Stick is a collaborative exhibition with artist Jess Bass which will be opening in September 2023. Our exhibition collages and interprets Jewish history, mysticism, and folklore to discuss the human impulse, throughout time, to imbue matter with souls and narrative. It will take the form of a multi-channel installation accompanied by a puppetry-inspired play.

The second body of work is a series of interactive sculptures and environments created with dehydrated fruit, stained glass, sand, and metal, related to a play I have been writing for several years, Soccer Island. I intend to present this body of work in an interactive context, abstracting techniques from sandplay therapy, in which attendees will handle and play with the sculptures, world building scenarios, and create alternate endings for the Soccer Island play.

Beitzah, 2022, Chicago Artists Coalition Photograph by Ang Zheng Wooden cage, soldered crab, beeswax candles, treble hook, tree

How did you become introduced to the world of art environments?

I grew up in Poughkeepsie, New York, in the Hudson Valley under the influence of the large number of artists who live upstate and the profusion of art environments in the landscape. I grew up visiting Harvey Fite's monumental site Opus 40 outside of Woodstock and hearing about Clarence Schmidt’s built environment and home which no longer existed by the time I was born. I visited Russel Wright’s Manitoga, Storm King Sculpture Park, Dia Beacon, and the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College regularly throughout my childhood. Every place, although not specifically geared towards art environments, had connections to the landscape whether through sculpture gardens or manipulation of nature. Growing up, I saw artists selling work on the side of the road and out of their homes, where the homes are themselves environments for art — an especially common practice among self-taught artists. I was always drawn to self-taught artists who embodied a maximalist sensibility, either in their work ethic — decade long pursuits at building art environments — or in their personality — the artist as extension of their practice, a character in their own created world.

An Oil Opera, 2020, Open sheds used for what? - El Paseo Garden Performance by Aida Ramirez and Gabriel Chalfin-Piney

Left Ear Solid Perfume - lemon verbena, lavender, eucalyptus, beeswax and jojoba oil Right Ear Solid Perfume - grapefruit, basil, copaiba, beeswax and jojoba oil

Oranges on the Seder Plate, 2022, Chicago Artists Coalition Photograph by Ang Zheng

Crab, mountain goat, linseed oil, candelilla wax, metal bells, wooden porch fencing, soldered water chestnuts/witches nipples, crucifix pendant, nest, black locust branch, potting soil, wooden back scratcher (yad), soldered wooden egg (beitzah), beeswax candles, plywood, potting soil, wooden cornices, angel candle snuffer

What about this type of art making is interesting to you? What sites have you visited, and what have you learned from those experiences?

The spirituality and storytelling that is often so integral to these environments is what initially drew me in, as well as the lack of formal art training that went into the creation of the sites. Growing up, I regularly visited the Bread and Puppet Theater’s community in Glover, Vermont. I was mesmerized by the scale and power of the storytelling across the puppets and sets displayed, and the love imbued in the collective vision and politics of Bread and Puppet. My interest in art environments continued in subtler ways as I participated in DIY venues and got involved with live-work communities. The ability to see new worlds born in spaces built out by artists, or attend a puppet show taking place in a dairy barn, all set the foundation for my own practice and my connection to this type of making.

Whenever I travel I check SPACES and create a route with intentional detours to art environments on the way. I’ve been lucky to visit a lot of places over the last few years. Since 2020, I have visited the following sites:

- Isaiah Zagar’s Magic Gardens and Willie Jordan’s home in Pennsylvania

- Grover Cleveland Thomson's Sunnyslope Rock Garden in Phoenix, Arizona

- The Second Coming House: Home of Prophet Isaiah Robertson in Niagara Falls, New York

- Worden’s Ledges in Hinckley, Ohio

- Holy Land USA in Waterbury, Connecticut

- The Bread and Puppet Theater in Glover, Vermont

- Dickeyville Grotto, James Tellen Woodland Sculpture Garden, and Nick Engelbert’s Grandview in Wisconsin

- Peter Beerit's Nervous Nellie's Jams & Jellies, Nathan Nicholls's Recycle Art Gallery and Bernard Langlais' art preserve in Maine

- Simon Rodia's Nuestro Pueblo (Watts Tower) and Elmer’s Bottle Tree Ranch in California

Which environments are on your list to see next?

Cano's Castle in Antonito, Colorado, Dr. Charles Smith's African American Heritage Museum in Hammond, Louisiana and the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, California are all at the top of my list, but more realistically some local art environments. I recently moved back to Chicago, so I am trying to visit as many of the Wisconsin places I haven’t been to including: Dr. Evermor’s Forevertron, House on the Rock, Paul & Matilda Wegner Grotto, JMKAC's Art Preserve, Rudolph Grotto Gardens, and the forever northern destination Fred Smith’s Concrete Park. I am also eager to make a trip to The Fiberglass Mold Graveyard in Sparta, Wisconsin, an art environment but perhaps not on purpose.

How does your interest in art environments (as a genre or specific sites) impact your own practice?

I have been drawn to found objects and material collections, often amassed through endless visits to antique and junk shops. These visits have taken on a meditative quality over the last few years, a sensation similar to what I experience during extended periods of time in nature or at a museum. These objects have lived many lives, and the ability to stand the test of time is often what draws me in to certain objects. There is a tension between these weathered objects, bound up in various histories and the ephemeral quality of the artworks I create. Whether they are a brief performance, a temporary installation, or a citrus fruit molding over time, I am drawn to the polarities of preservation and physical degradation of objects and stories.

I often use these collections in my sculpture and performance works, they take the form of ritualized objects often drawing inspiration from Judeo-Christian practices and stories, often accompanying objects that I have made using natural and found materials. This focus on Judaica was brought on in part by observing the highly saturated Christian imagery that populates many art environments, especially grottos. I want to interrogate the histories I grew up with and bring the practices and values of Pro-Palestinian Jewish folks with me.

The world of art environments has also been an ego-check for my artistic practice and has taught me the importance of patience and building practices imbued with care. In 2010, when I first started studying fine art in college, I sensed a shared eagerness in my cohort of late teens and a forced rush to get my career started, and an academic push towards building relationships I could benefit from after graduation. Having visited more and more art environments over the last few years and read more about the makers, I have been moved by the longevity of these sites, the sometimes daily practice of making over many years, and the repetitive meditative quality that this type of making takes on. Over the last decade, I have come back to a show I saw in 2013 at the Queens Museum, Peter Schumann’s “The Shatterer,” the first solo museum exhibition of Bread and Puppet Theater’s founder and director. Schumann was in his late 70s when this solo exhibition was produced. The show has been a constant reminder to me that recognition from the Art world is worth very little and impact happens on a slow scale, year after year. I am grateful for the ability to pause, it has given me the gift of knowing that there is no rush, no destination.

i like your earring, 2020, Open sheds used for what? - El Paseo Garden Collaborative installation by Kayla Taylor and Gabriel Chalfin-Piney

Tattooed grapefruits and clay objects

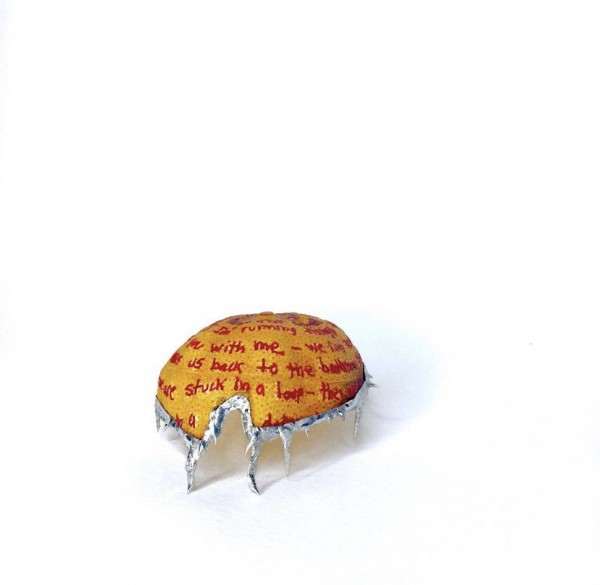

Saint Seraphim’s Body (A Crab), 2020 Dehydrated grapefruit tattooed May 18, 2020, soldered metal

This interview with Gabriel Chalfin-Piney was conducted by Annalise Flynn via email January 2023.

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.